John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Click to read the full report “Staying Connected: Keeping Justice-Involved Youth 'Close to Home' in New York City."

For years, many juvenile offenders in New York City had been exiled to upstate facilities — hundreds of miles from families, schools and communities.

This continued despite mounting evidence that keeping such youth closer to home improves the odds of reducing recidivism, continuing their progress in school through their local school systems and helping them successfully re-enter the community.

Now, a report by the Research and Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City shows promising early results of a city-state program called “Close to Home.”

The report found that the program, which began in 2012, has helped youths maintain closer ties with families, schools and communities — all viewed as vital to successful rehabilitation. It has drawn strong support from state and city officials as well as juvenile justice experts and advocates.

The report — by the Research and Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City — comes at a time of growing recognition that keeping juvenile offenders closer to home improves the odds of reducing recidivism, continuing their progress in school through their local school systems and helping them successfully re-enter the community.

“The things we do know are you accomplish nothing by putting a kid in a faraway facility,” said Jeffrey A. Butts, director of the center and the report’s lead author. “There’s no benefit to having them there. So you don’t get anything from that.

“It doesn’t take a real stretch to say if you’re working with a kid in a residential bed, if the family can visit a lot, that’s good. Also, if that young person can stay in touch with their local school and continue to get credits from their local school and not lose educational progress during a time of residential placement, then that’s a good thing,” he said. “And those things are now possible, and they were not before.”

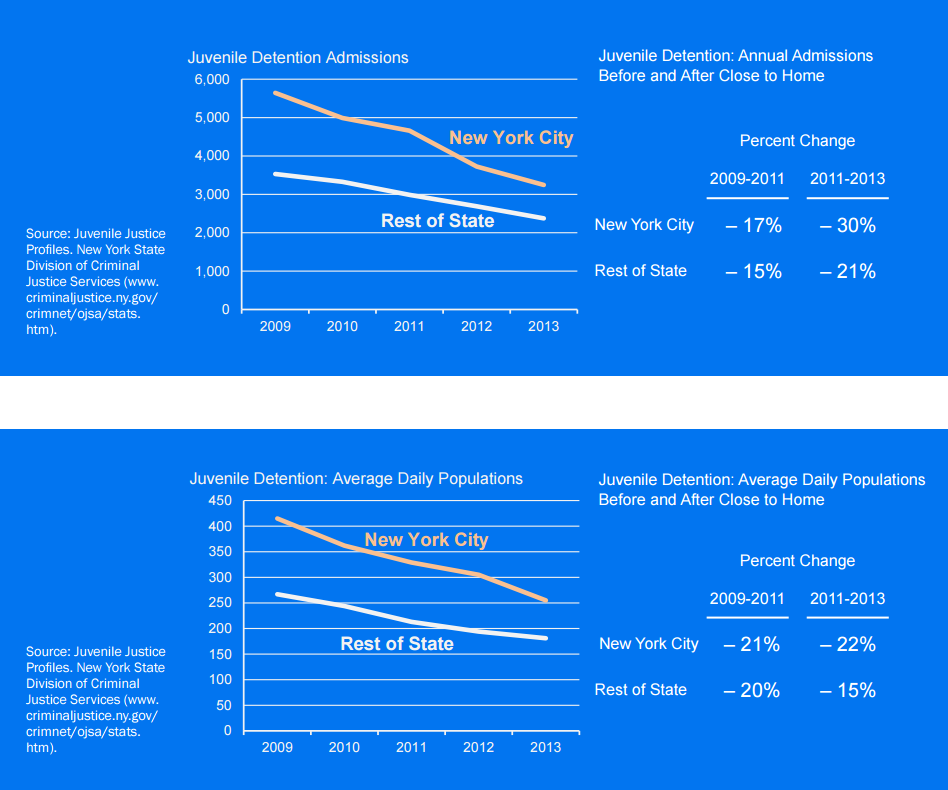

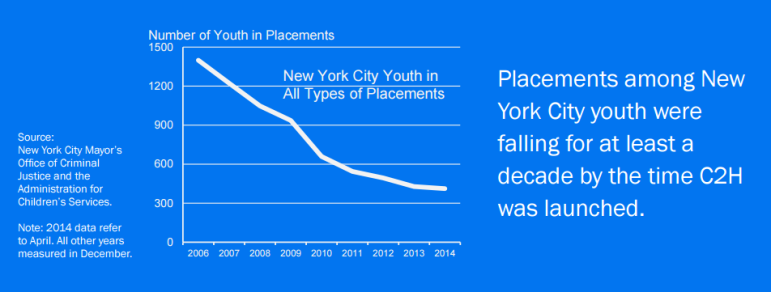

However, Butts said it will take further research to determine whether Close to Home has reduced crime, as juvenile delinquency in the New York City area had been declining years before the program began.

However, Butts said it will take further research to determine whether Close to Home has reduced crime, as juvenile delinquency in the New York City area had been declining years before the program began.

“When justice-involved youth are supervised by local agencies and placed with locally operated programs rather than being sent away to state facilities, they are better able to maintain community ties,” the 44-page report stated. “They stay connected with their families and they are more likely to remain in local schools.

“Increasingly, public officials are reforming youth justice systems by relocating the bulk of their intervention resources at the local level. Many states are investing in community-based alternatives and some are closing down traditionally rural, state-operated youth correctional facilities.”

Close to Home provides a prominent example of what juvenile justice experts call “realignment” in placing youths, which the report called the “latest chapter in a decade-long commitment by New York State and New York City to improve the justice system for young offenders by investing in programs and interventions that allow youth to stay close to their homes and families.”

More evaluation will come after the start this spring of the second phase of the program, which will increase the number of youths and include more serious offenders while expanding the program’s focus. The first phase involved about 200 offenders.

Researchers, led by Butts, interviewed numerous experts involved in planning Close to Home and found the program “successfully changed the youth justice system in New York City, and in the way intended by the designers of the reform.”

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Click to read the full report “Staying Connected: Keeping Justice-Involved Youth 'Close to Home' in New York City."

The report found out-of-home New York City delinquency placements declined from 544 in 2011 to 415 in April 2014, but again stressed those numbers had been dropping before the program began.

The number of youths in state-run facilities that are the report’s focus dropped precipitously, from 87 in 2011 to six in 2014.

Mishi Faruqee, who served on planning committees for Close to Home, said its vision “wasn’t about a bed transfer; it wasn’t about just taking all the beds that were upstate and then building beds in New York City. It was really about expanding community-based options for people after adjudication. It focused on what types of community-based options we should be looking at.”

Faruqee, juvenile justice policy strategist with the American Civil Liberties Union, noted that before Close to Home, upstate facilities did not provide transferable credit for New York City youths. “Education was really about looking at how we could have seamless education for young people who were part of the Close to Home system,” she said.

Before 2010, many youthful offenders in New York had been referred to “evidence-based” family therapy programs when in some cases such therapy might not be what they needed at all, she said. A kid might be dealing drugs to help support his family, for instance, while a youth caught shoplifting may need an apprenticeship or job training, she said.

The best outcome, of course, is not just to keep kids close to home but in their family homes with treatment or monitoring, as necessary, Faruqee said.

Butts said some advocates and officials had expressed concerns that Close to Home could lead to an overall expansion of the system — or “net-widening” — as opposed to merely replacing state placements with local placements, as courts and police became more aware of the local options.

That has not happened, however, Butts said.

The report also said that while the initiative was not designed to reduce costs, “many officials believe it will eventually make youth justice more cost-effective by generating better outcomes and lowering crime.”

Butts said perhaps the only downside of Close to Home is for upstate communities that lose jobs from juvenile facilities.