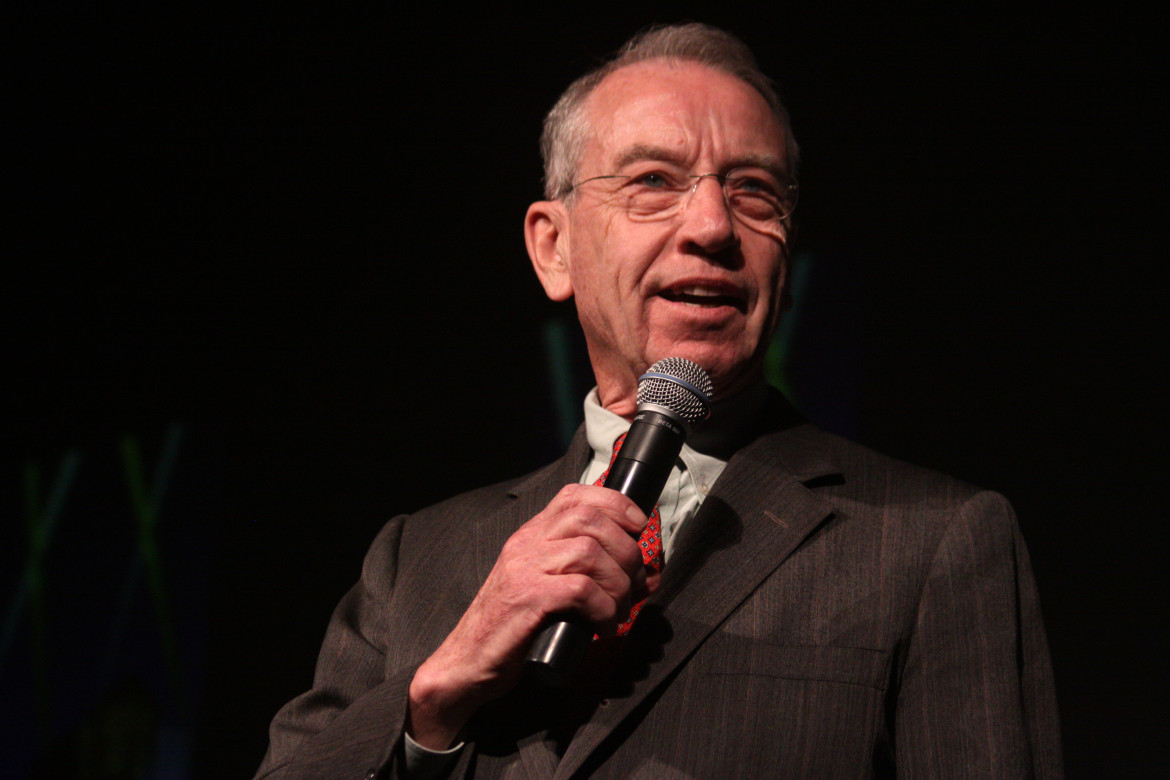

Gage Skidmore / Flickr

U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley

WASHINGTON — The primary U.S. juvenile justice law, the 1974 Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA), would undergo its first major overhaul in two decades under a bill to be introduced this week.

Sen. Charles E. Grassley, R-Iowa, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, announced the impending introduction of the bipartisan measure, co-sponsored by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., at a news conference at the National Press Club today.

The JJDPA had originally been designed to protect youths in trouble with the law, preventing them from being housed with adult criminals, for instance. It was also meant to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice and bar detention of children for “status offenses” like skipping school. Status offenses are so named because they’re crimes only by virtue of the offender’s status of being a juvenile.

Not coincidentally, the reauthorization bill comes after a Senate Judiciary hearing last week in which whistleblowers testified that the Justice Department had for years continued to give millions of dollars in federal juvenile justice grants to states that put vulnerable children in adult jails and prisons in violation of federal law.

Witnesses also pointed to lax enforcement of four “core requirements” of the JJDPA and the nearly 400 pages of cumbersome federal regulations that enforce them.

“Let’s start with the youngest of those facing the criminal justice system,” Grassley said Monday. “This is a program that not only helps prevent at-risk youth from entering the criminal justice system, but also one that helps rehabilitate minors already in the system.”

And on the day that Loretta Lynch was sworn in here as the new U.S. attorney general, Grassley criticized the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs under Eric Holder.

“The whistleblowers [at the Judiciary hearing] testified to widespread mismanagement and failures in the grant program,” Grassley said. “They cited instances of fraud and neglect of core grant requirements for these taxpayer-funded grants. The Justice Department’s negligence relates to implementation of the four criteria states must meet to receive funds.”

He said a “few states” meet all grant eligibility criteria. “But,” he added, “the Office of Justice Programs, which administers the program, turns its head the other way when states aren’t in compliance. Worse yet, states know about this blanket amnesty, so apparently they don’t even try to follow the law.”

After an exchange of letters among Grassley, OJP Assistant Attorney General Karol Mason and Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Administrator Robert Listenbee, Grassley said today, “The Justice Department finally owned up to some of these problems. They admitted to having a policy in place since 1997 that allowed states to obtain federal funds in violation of the law, and they have assured me that they will end this practice. However, other issues remain.

“So, we’re going to start righting those wrongs this week.”

The reauthorization bill, he said, would strengthen core requirements to protect youths while also responding to issues raised by whistleblowers by increasing accountability in the OJP and OJJDP’s administration of the law.

The legislation has not been drafted, Grassley spokeswoman Beth Levine said.

However, sources said it is expected to closely resemble a measure Grassley and Whitehouse introduced in December, perhaps with more stringent oversight following the Grassley-led inquiry.

That December bill called for out detention of status offenders. A recent study by the Washington-based nonprofit Coalition for Juvenile Justice found more than half of U.S. states allow children to be detained for repeated status offenses.

The new bill also is expected to give states financial incentives to provide alternatives to lockup for nonviolent offenders. Reams of research shows that jailing nonviolent youths typically does more harm than good and can lead to more delinquency and even to incarceration as adults.

Underlying many of the changes to the bill would be recent research on adolescent behavior and brain development, Grassley’s office said. The research has found adolescent brain development can continue until age 25. Youths can be impulsive, reckless, prone to peer pressure and tend to not take into account long-term consequences of their actions. But the research also shows almost all youths participate in delinquent behavior but most of them outgrow it.

The bill also would:

- Give teeth to the core requirement on dramatically reducing racial and ethnic disparities. The current law requires states that receive juvenile justice grants to address “disproportionate minority contact” with the justice system and take steps to reduce it, but has been criticized for not being tough enough.

- Significantly reduce the number of youngsters placed in adult jails.

- Promote alternatives to incarceration.

- Improve conditions and educational services for incarcerated youth.

Juvenile justice advocates hailed the upcoming bill.

"The introduction of a bipartisan JJDPA bill is the first step towards updating the law,” said Liz Ryan, president and CEO of the Washington-based nonprofit Youth First! Initiative, which seeks to reduce youth incarceration and provide community alternatives. “It is very important, as it provides the vehicle to address the most pressing issues in juvenile justice today, including reducing racial and ethnic disparities, reducing detention and incarceration, and keeping kids out of adult jails.”

Ryan said she believed last week’s Judiciary hearing “provided a much-needed sense of urgency in moving the JJDPA reauthorization forward.”

And Marcy Mistrett, CEO at the Washington-based nonprofit Campaign for Youth Justice, exclaimed, “This is great news! The JJDPA is an important law that improves the lives of children who come in contact with the justice system.”