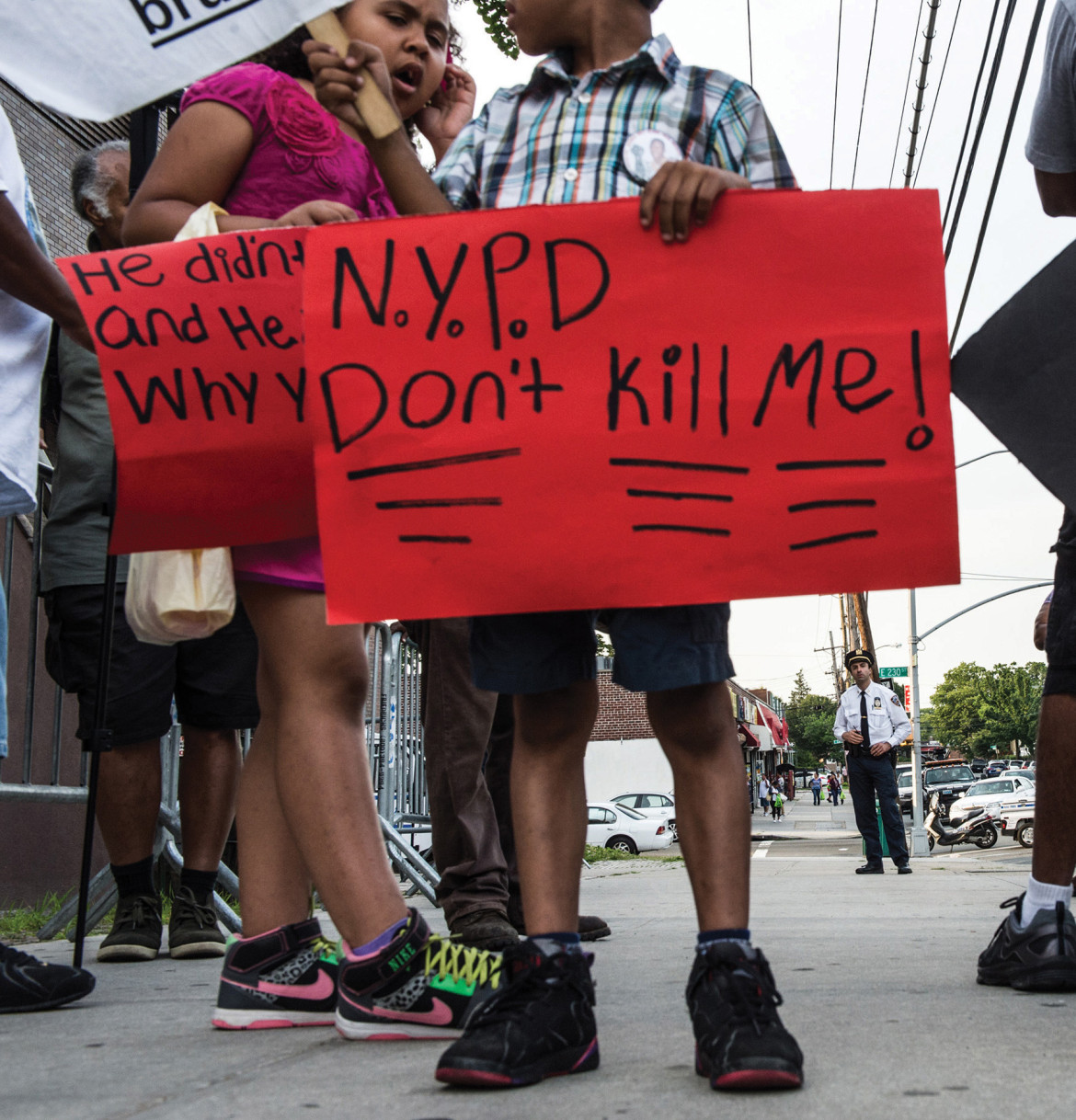

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

A young protester has a powerful message.

NEW YORK — The oldest killing on the list dates back to Aug. 23, 1994; it happened with a gun in a stairwell in a Brooklyn housing project. The most recent is July 17 of last year; it happened in plain sight with a chokehold and was recorded and broadcast to the world.

Nicholas Heyward, the father of Nicholas Heyward Jr., and Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, are on a list no one wants be on. They are the father and mother of children killed by the police in New York.

They joined other family members in signing a letter delivered to state lawmakers in Albany this morning imploring them to enact a law that would create a special prosecutor to investigate killings at the hands of the police.

The letter comes a month and a half after several mothers on the list met with Gov. Andrew Cuomo to ask him to sign an executive order to create the special prosecutor, bypassing political wrangling in the state capital.

Constance Malcolm, whose son Ramarley Graham was gunned down in his own home by police officer Richard Haste, was one of them. At that meeting, Malcolm said Cuomo promised to expand authority to the Attorney General’s office so that it could investigate police killings if a bill he supports does not make it through Albany. He said he did not have the power to appoint an independent special prosecutor.

The reform is one that activists are calling for around the country in the wake of high-profile killings of blacks and Latinos at the hands of police that have resulted in no indictments. In Cleveland, the family of Tamir Rice — a 12-year-old shot by police while playing — have resorted to citing an arcane law allowing them to circumvent a prosecutor’s office that they do not trust to conduct a fair and impartial investigation.

The reform is one that activists are calling for around the country in the wake of high-profile killings of blacks and Latinos at the hands of police that have resulted in no indictments. In Cleveland, the family of Tamir Rice — a 12-year-old shot by police while playing — have resorted to citing an arcane law allowing them to circumvent a prosecutor’s office that they do not trust to conduct a fair and impartial investigation.

One of the main roadblocks, aside from the upstate-downstate ideological rift that defines New York state politics, is that the District Attorney’s Office bristles at the idea of outside investigators coming into their jurisdiction and are resistant to surrendering some of their authority to another agency.

In New York City, activists calling for reform have argued for decades that the New York Police Department and the prosecutors’ offices in the five boroughs work together too closely to have them be honest arbiters in investigating police abuse.

In the wake of the shooting of Sean Bell, who was killed in a fusillade of 50 bullets fired by members of the NYPD in 2006, the department conducted a parallel investigation that often bumped up against the one the Queens district attorney’s office was trying to do.

In the face-to-face meeting in April, Cuomo said he wanted the legislative process to run its course.

But activists calling for comprehensive reform say the governor’s reforms being considered by the legislature do more to undermine the demands of the families of slain children than it does help them. It includes an independent monitor that activists say is a toothless half-measure that does nothing to hold accountable local police departments around the state, especially a juggernaut like the NYPD, the largest police department in the continent.

“The independent monitor the governor is promoting goes beyond inadequate to being counter-productive,” said Loyda Colon, co-director of the Justice Committee. “It does not address the systemic problem. It only creates another step in the process, and leaves the appointment of a special prosecutor up to discretion. It is a proposal that the state Legislature should not support.”

Malcolm, who has dedicated her life to police reform in the wake of her son’s death, said she does not want to wait any longer.

“We want him to stop playing politics with our children’s lives,” she said, urging the governor to not wait and sign the executive order immediately.