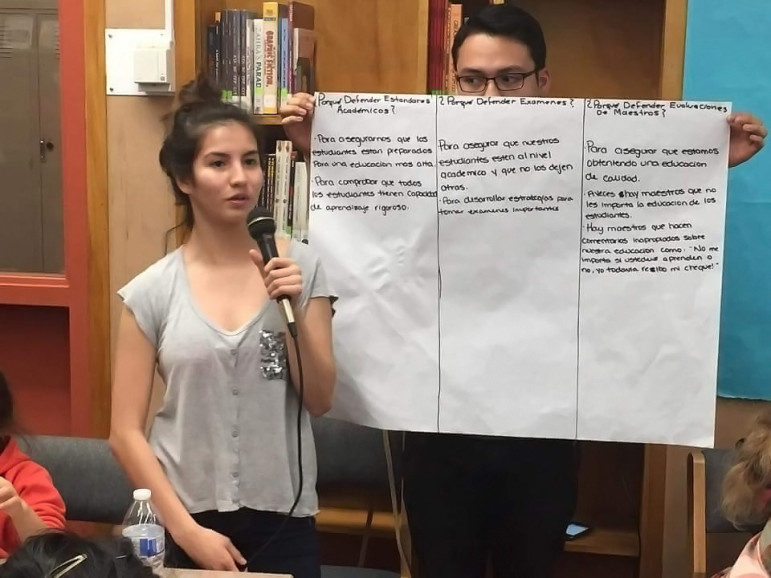

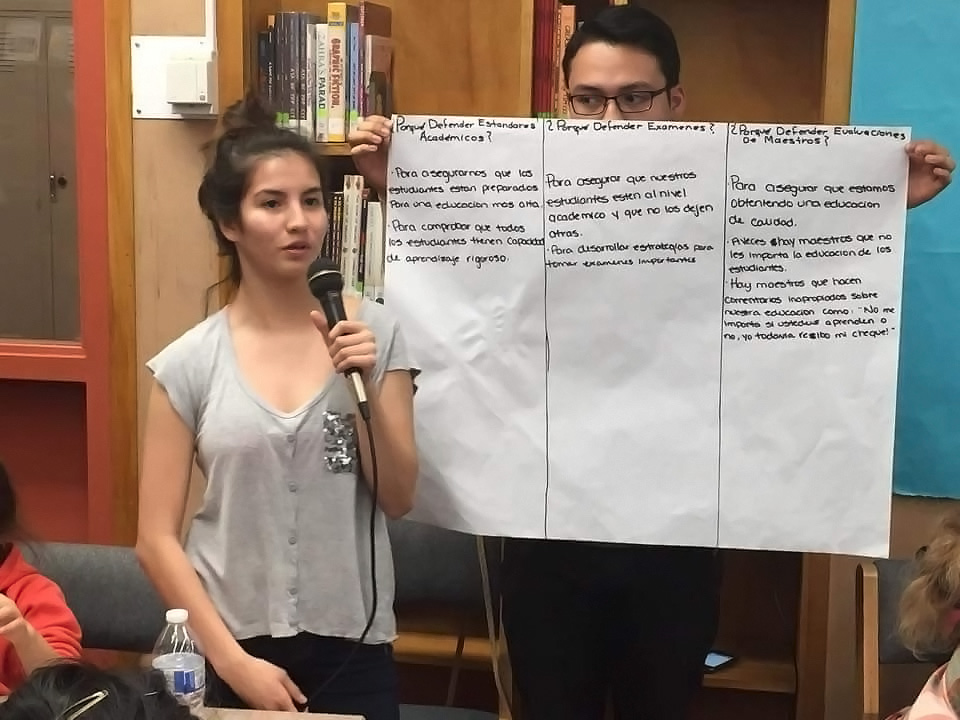

Padres & Jõvenes Unidos

Patricia Cardenas, a student leader working with Padres & Jõvenes Unidos, informs Denver students on how to get their disciplinary records expunged before they apply to college. Read her story in "Denver Group Wants School Discipline Records Automatically Purged."

The first time 18-year-old Isaac came across a question on a college application that asked if he had ever faced disciplinary action in high school, he decided to be honest and checked the “yes” box.

Asked for more information, he provided details about getting caught on video exiting a school bathroom with a female student. The cameras didn’t catch the pair in the act, but they left considerable evidence behind.

“We commended him for his honesty but then we had to redirect him in the way that he expressed what happened,” said Jason Harris, a college adviser who assisted Isaac (not his real name) on his college applications through College Now Greater Cleveland, a nonprofit that provides advising, scholarships and other services to 22,000 students.

“We had to just say: ‘It’s great that you’re honest, but you have to realize the way that you’re speaking sounds like you’re speaking to your boys instead of talking to someone who theoretically holds your acceptance in their hands,’” Harris said.

Isaac took a completely different tack when he applied to a prestigious college that only admits about 10 percent of its applicants — he checked the “no” box when asked if he had ever been disciplined in high school. By now, he had gotten wise to the fact that colleges had no way to find out about the incident since the Cleveland Metropolitan School District doesn’t provide colleges with disciplinary records.

But that is not always the case.

A groundbreaking new study, conducted by the Center for Community Alternatives (CCA), a New York-based organization that advocates on behalf of students who have had prior court involvement, found that half of all high schools disclose disciplinary information as requested, at least in some cases.

Specifically, 26 percent of high schools always disclose disciplinary information as requested, and 24 percent disclose the information "in some cases." Fifty percent do not disclose the information.

The study, “Education Suspended: The Use of High School Disciplinary Records in College Admissions,” also found that roughly three out of four colleges and universities collect high school disciplinary information, and that 89 percent of them use the information to make admission decisions.

Defenders of this use of high school disciplinary records say it is an important way for universities to keep undesirable elements off their campuses.

Todd Rinehart, associate vice chancellor of enrollment and director of admissions at the University of Denver, said he disagreed with the report’s recommendation that high schools should stop providing disciplinary records, and that colleges should stop asking for them.

“The school districts currently not reporting their disciplinary infractions; they should be,” said Rinehart, who is also chairman of the admissions practices committee of the Arlington, Va.-based National Association for College Admission Counseling. NACAC collaborated with CCA to administer a survey of colleges that serves as the foundation for the CCA study.

“When we’re doing a holistic review, we’re really shaping a community,” Rinehart said. “We should have every bit of information that’s possible.”

But opponents, including the authors of the CCA report, say high school disciplinary records have little predictive value, needlessly stigmatize students for infractions that are often minor and reduce their opportunities for higher learning.

They also say the practice raises civil rights concerns because of the well-documented fact that students of color are disciplined at higher rates than their peers.

While African-American students comprise 18 percent of school enrollment, they represent 35 to 39 percent of students suspended or expelled, making black students three times more likely to be suspended than white students, the report says. Prior research has found the disparities exist even after controlling for socioeconomic status, the report observes.

“I think the likelihood of misuse, misapplication and injustice along the lines of race, disability status and gender far outweigh using such a simplistic form,” said Daniel J. Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies, an initiative at the Civil Rights Project at UCLA.

“They’re asking has the student ever been found responsible for a disciplinary violation resulting in a disciplinary action,” he said. “That’s a very broad question and could definitely lead to a student who is otherwise in good standing being denied access to college on a dress code violation or repeated tardiness.”

Rinehart, of NACAC, said such infractions seldom result in students’ college applications being denied. On the other hand, he said: “If the student has done something severe and has a pattern of bad behavior, in my mind, the college or university has the right to know that and not offer admission.

“It doesn’t mean they’re denying the student to higher education,” Rinehart said. “It is a privilege to be admitted to individual institutions.”

Students with serious disciplinary issues seldom have stellar academic records and are likely to have been rejected anyway, he said. He did not dispute that students of color may be more apt to have disciplinary files due to unfair disciplinary practices but said that is no reason not to seek the files.

“The solution isn’t to say, “Let’s not ask the question,’” Rinehart said. “Let’s address the inequities and the inconsistencies.”

CCA says rates of rejection based on disciplinary records need to be quantified and studied further before anyone accepts colleges’ assertion that not many students are rejected because of something derogatory in their high school disciplinary records.

Jason Sinocruz, staff attorney at the Advancement Project

Jason Q. Sinocruz, a former college admissions officer at Stanford University who now works as a staff attorney at the Advancement Project, a civil rights organization based in Washington, D.C., said there is little doubt that disciplinary data has a negative impact on a student’s college application.

“Whenever there is a disciplinary record on file, that application is almost immediately flagged for a review, if not sent straight to denial,” Sinocruz said. Even training for admissions officers cannot undo the damage done when a student or school official checks a box indicating that the student has been disciplined in the past.

“There’s a bias effect,” Sinocruz said. “If I see a student has been disciplined three times for ‘insubordination,’ ‘disrespect,’ some of these categories that are overly vague and capture very minor incidents, it’s hard not to look at the students as somehow disrespectful, even if it was for a minor thing.

“A lot of times the categories that are used are much stronger, much more punitive-sounding than what actually happened.”

Most high schools — nearly 63 percent — lack formal, written policies about disclosure, the report said. At 41 percent of the high schools that disclose disciplinary information, the school counselor is the only person to review the information before sending it to colleges.

Shari Sevier, board chair of the American School Counselor Association, said written policies are “very beneficial.”

She said the school district where she works, the Rockwood School District, decided to release information “only when asked” and only for cases when a student was put out of school “because those are the more serious offenses.”

“That being said, some of those offenses can be nothing that I would be concerned about on a college campus,” said Sevier, a counselor at Lafayette High School in Wildwood, Mo. “Many times the infractions are of things that a 14- or 15-year-old did and it’s one of those kind of crazy things, crazy kid things.”

I was kicked out of school in my sophomore year of high school and I graduated magna cum laude with no disciplinary problems at my college. I do not think our high school lives should be a big part of deciding if we should be accepted or not.