“One-Way Ticket”

I pick up my life

And take it with me

And I put it down in

Chicago, Detroit,

Buffalo, Scranton,

Any place that is

North and East —

And not Dixie.

I pick up my life

And take it on the train

To Los Angeles, Bakersfield,

Seattle, Oakland, Salt Lake,

Any place that is

North and West —

And not South.

I am fed up

With Jim Crow laws,

People who are cruel

And afraid,

Who lynch and run,

Who are scared of me

And me of them.

I pick up my life

And take it away

On a one-way ticket —

Gone up North,

Gone out West,

Gone!

—Langston Hughes

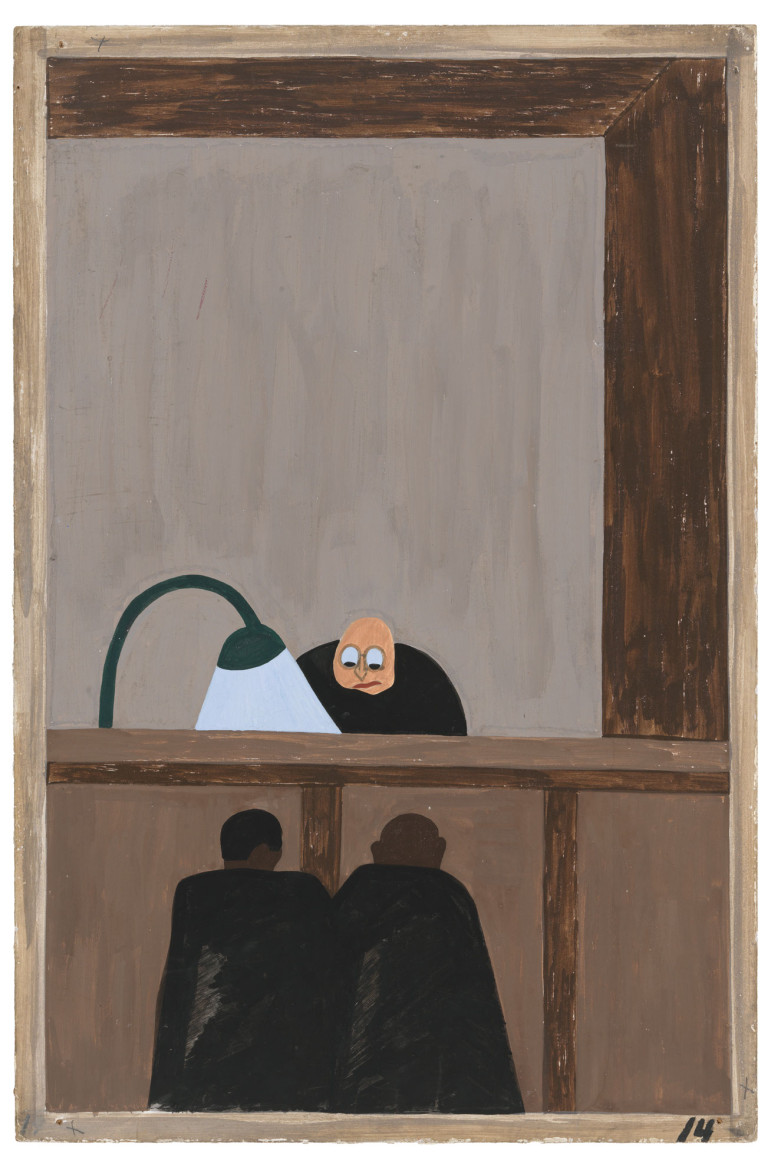

NEW YORK — The judge sits above the two defendants, both faceless black men seen from the back, standing so close together their jackets blend. It is hard to tell where one man begins and the other ends. The white judge is almost a cartoon character, his misshapen head sitting atop his dark robes. A cartoon judge dispensing cartoon justice, with catastrophic consequences for faceless defendants.

A narrow shaft of light from a green lamp illuminates what could be some documents or briefs. His demented, impossibly large googly eyes are fixed there, while he seems indifferent to the two men below him. The prisoners wait for this powerful figure to decide their fate.

A narrow shaft of light from a green lamp illuminates what could be some documents or briefs. His demented, impossibly large googly eyes are fixed there, while he seems indifferent to the two men below him. The prisoners wait for this powerful figure to decide their fate.

“Among the social conditions that existed which was partly the cause of the migration was the injustice done to the negroes in the courts,” reads a dispassionate caption next to the painting of the judge and his defendants.

This scene of racially corrupt justice is one of many that illustrate the role a racist and rigged criminal justice system played in influencing this staggering movement of black people from the rural cities to the urban north and Midwest. It is one of 60 paintings by Harlem artist Jacob Lawrence that until recently was being exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art. Langston Hughes' poem "One-Way Ticket" welcomed visitors to the exhibit.

At 23, Lawrence documented in rough brush strokes one of the largest migrations in the history of mankind when more than 6 million black people fled the South to come to northern cities.

From 1940-41 Lawrence researched and worked on a series he called simply “The Migration Series.” It tells the story of black families fleeing violence and looking for better economic opportunity.

Normally, the 60 panels are split between New York and Washington, D.C., with all the even-numbered panels at the Museum of Modern Art and the odd-numbered ones at the Phillips Collection in Washington.

MoMA had assembled all the panels for the first time in two decades as part of a deeper exploration of this momentous and tumultuous period in American history in an exhibit called “One-Way Ticket: The Jacob Lawrence Migration Series and other Visions of the Great Movement North.” It was an exhibit that touched the young people who got to see it.

“Teenagers are always drawn to the judge,” said Calder Zwicky, assistant director of teen and community partnerships. “They feel that sense of power he has over these two guys. He’s sitting up there with the bulging eyes looking down. He can do whatever he wants to these guys. Young people get that feeling, that feeling of helplessness, whether it’s a principal at school who won’t listen to their side of the story, or a cop in the street stopping them for no reason. They really instinctively respond to that sense of helplessness.”

Robert Stolarik

Calder Zwicky, assistant director of teen and community partnerships.

There is a fierce urgency to Lawrence’s work, something MoMA organizers said they saw firsthand in the tours they gave to city youths. The panel of the judge, more than others, seemed to draw black youths to it. They often stood mesmerized, almost in a trance. When asked why that one painting, more than others, their response was often: “That’s how I feel.”

Shellyne Rodriguez, a MoMA community and access educator, remembers one tour of black and Latino young people in their late teens and early 20s shortly after the exhibit opened. One young man stopped at panel 14, fixated on the the demented judge and his bulging eyes.

“We always end up at the judge,” Rodriguez said. “I remember he turned to me and asked, how is that things can change and still stay the same?”

It is a question that shows Lawrence’s power.

Another member of the group, a girl, described an encounter with a police officer. He stopped and frisked her near her apartment in Harlem.

“The white cop told her, ‘I’m sorry to do this to you but the boss needs his numbers,’” Rodriguez recounted. “Of course the injustices of the present come up during the tours. It’s our history, and so much of it is still the same. … These stories are our stories, that history is our history.”

Kerry Downey, Rodriguez’s colleague at MoMA and a fellow artist and educator, also gives tours and has been struck by how easily Lawrence’s paintings speak to the problems animating the present.

“The strongest takeaway I’ve had is how the conversation Lawrence starts is relevant to what’s happening today,” Downey said. “You can turn on the news and see it playing out. … This conversation also brought us to police abuse and how they employ racial profiling. Many students really opened up about that sense of your skin color being equated with a threat by people in power, and that sense of feeling invisible that comes with that.”

Lawrence’s series takes a sweeping look at the racial and cultural atmosphere that blossomed as the monumental demographic shift that began early in the 20th century and ended in 1970 changed the face of the country.

In his 1920 book, “Negro Migration During the War,” Emmett J. Scott wrote, “They left as if they were fleeing some curse.” Lawrence’s paintings capture that sense of almost apocalyptic desperation.

[Related: After Decades of Spending, Minority Youth Still Overrepresented in System]

The exhibit feels at times like an illustrated doctoral dissertation, but with the artistic resonance of an early Renaissance fresco.

Lawrence’s brush chronicles everything from the mad rush for the trains to the rotting crops left behind in untended fields as black farmers fled lynchings, arbitrary treatment from police and courts, mistreatment by white farmers who ran the tenant system and daily degradation under the terror of Jim Crow. He showed a new life in the burgeoning cities in the North, the influential role of the black press in encouraging people to abandon the South and the letters black migrants sent back to the South about their new lives.

The paintings are deceptively simple. Each manages to capture a moment that is at once intimate, one person’s experience, and simultaneously on a staggering scale.

“One of the reasons the show is powerful is that it allows us to have a conversation not just about art and history,” Rodriguez said. “But it’s also about issues that get glossed over in traditional history lessons — police violence and the legacy of the American justice system. All of these are things affect us intensely right now. People want to talk about them.”

Seydou Horvilleur, 17, is visiting New York City from France, staying with an American family. Horvilleur, who is black, said he was cautioned by his host parent to not challenge any police officers if they stop him for any reason. He said she was more worried about what could happen to him in an encounter with a member of the New York Police Department than with a common criminal.

“We don’t learn much about the black American experience in Paris and the rest of France,” he said. “I always thought that they left for economic reasons. But I just read that they were running from the South because they didn’t feel safe. And it seems a lot of what is happening here in New York and across the country is that black people are out there saying the same thing — that they don’t feel safe.”

“Mommy, mommy,” a little girl shouts, running up to Lawrence’s 22nd panel in the series. “They’re in jail! Why are they in jail, mommy?”

“You are right, honey,” the girl’s mother replies. “They were arrested.”

“Why?” asks the girl, Ranii Reed, 9.

“I don’t know,” her mother Tash Reed, 35, responds. “I don’t know.”

Lawrence’s 22nd painting depicts three black men in threadbare jackets seen from the back. They’re handcuffed with gold shackles to one another and staring out a barred window. The caption, in Lawrence’s dry matter-of-fact tone, reads: “Another social cause of the migrants leaving was that at times they did not feel safe or it was not the best thing to be found on the street late at nights. They were arrested on the slightest provocation.”

Reed tries to explain to her daughter the best she can that people who looked like her did not always get a fair shake in the old days. But it’s hard; her daughter is young and has trouble understanding.

Reed was visiting the museum from Winter Haven, Fla. She said the exhibit made her think about her family’s journey. It’s something she can’t tell her daughter, because she doesn’t know herself.

“I don’t know where we came from,” Reed said, looking around at Lawrence’s paintings. “It’s amazing to see what the artist did, to try to teach us about ourselves.”

She said seeing the paintings of desperate people caught up in the mass exodus makes her think about the struggles people still face today.

“You see how poor they are,” she said. “Most look like they didn’t have too much of anything. It makes you think about how things have gotten better, but also about how much it hasn’t. You look at these paintings and you know there are people out there, poor people, that are still out there. A lot has changed, a lot has changed but it hasn’t changed enough.”

Frinsel Guillaume, 29, had a similar visceral reaction to the exhibit. Guillaume, who lives in Jersey City, N.J., said he sees echoes of the paintings outside his window.

Frinsel Guillaume, 29, had a similar visceral reaction to the exhibit. Guillaume, who lives in Jersey City, N.J., said he sees echoes of the paintings outside his window.

“I see it all the time,” he said. “It’s a common occurrence with kids in my neighborhood. Police have been patrolling my neighborhood all summer throwing kids against the wall for nothing.”

He, too, was drawn to the scene of the judge.

“There’s just this incredible sense of injustice,” he said. “It’s the same injustice you see today. There’s these two young people versus one judge. You know they don’t have a chance whether they’re guilty or innocent. And you can’t see their faces, you can only see the color of their skin.”

Now with the country in the grips of a tense national conversation over what — if anything — can be done to curb police violence in black communities, Lawrence’s exhibit ends on a troubling note. Millions of black residents fled terror for freedom. Their descendants are residents of the big cities like New York City.

The last panel of the exhibit shows a crush of faceless black figures standing at a train station. It could be anywhere — the Florida Panhandle, Alabama, Tennessee — waiting to be delivered to new lives in new towns.

Guillaume somberly shakes his head as he stares at the crush of people. “At least they had somewhere to go,” he says aloud to no one in particular.

Lawrence’s caption to his final painting reads: “And the migrants kept coming.”

What Lawrence never answers is what happens when the migrants finish their journey but realize that the injustice continues. Where do you go to buy your next one-way ticket? And where is the destination if there is nowhere left to go?

More articles related to this one:

Opinion: Time to Take Closer Look at Race in Juvenile Justice System