Juvenile Law Center

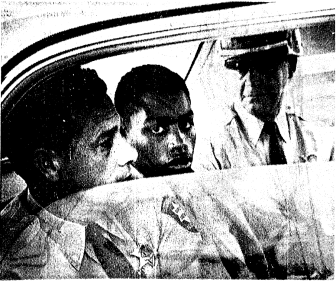

Marsha Levick, co-counsel on Montgomery vs. Louisiana and deputy director of the Juvenile Law Center, is interviewed outside the Supreme Court following oral arguments. Courtesy of Juvenile Law Center,.

WASHINGTON — More than 50 years after Henry Montgomery went behind bars, the Supreme Court took up his case today so as to decide whether prisoners serving mandatory life without parole sentences for murders they committed as juveniles should have a chance at release.

In 2012, the justices ruled 5-4 in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles (JLWOP) are unconstitutional on Eighth Amendment grounds.

Now, in Montgomery v. Louisiana, the question for the court is whether the Miller decision should apply retroactively. If the justices rule it should, as many as 2,100 prisoners across the country would qualify for a resentencing hearing.

Montgomery has spent decades in prison since he was convicted in the shooting death of sheriff’s deputy Charles Hurt in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1963. He was 17 at the time of the murder.

During oral arguments, the justices focused on two questions: whether they have jurisdiction to hear the case and whether Miller set out a new substantive sentencing rule, as opposed to a procedural one.

The latter question depends on an analysis of Teague v. Lane, which sets standards for whether new rules should be retroactive based on whether they are substantive.

Montgomery’s lawyers have argued Miller is substantive and therefore retroactive because it bars a category of punishment from being imposed on a category of defendants.

However, lawyers for Louisiana say Miller is only procedural because the decision still allows for a sentence of juvenile life without parole at the discretion of a judge or jury that considers factors such as age or potential for rehabilitation.

“Leaving the punishment on the table is critical,” said S. Kyle Duncan, a lawyer for Louisiana, during the argument.

Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote the Miller decision, questioned Louisiana’s interpretation during the arguments. She said there is a process component to Miller — establishing factors juries and judges should consider when juveniles are being sentenced for murder — but it is not the only component of the decision.

“What the court has done is say, ‘There have to be other options,’” she said.

Marsha Levick, co-counsel for Montgomery and deputy director and chief counsel for the Juvenile Law Center, said after the session that Kagan’s line of questioning was welcome.

“Her questions seemed to suggest that she felt it wasn’t just about process,” she said.

The landmark Miller decision was the latest in a series from the court rooted in the idea that children should be treated differently than adults because they are less culpable for their actions and have the potential to change.

“Mandatory life without parole for a juvenile precludes consideration of his chronological age and its hallmark features — among them, immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences,” Kagan wrote for the majority in the decision.

However, much of Tuesday’s arguments focused not on Miller, but on whether the Supreme Court has jurisdiction over the case.

Lawyers for both Montgomery and the state agree the court has jurisdiction. However, because the court itself has questions, a court-appointed lawyer argued against that position.

The central issue stems from Louisiana’s decision to apply the Teague standard to its ruling that Miller is not retroactive. The court wants to know whether that voluntary choice makes the case a state or federal question.

The court will have to decide whether it has jurisdiction before considering the retroactivity question.

If the court declines the case, Duncan said after the session, that won’t be the final word.

“The court will have to reach the merits at some point because there are many cases presenting the same issue,” he said.

Resentencing hearings

Should the court decide in Montgomery’s favor, then prisoners across the country would be eligible for resentencing.

Levick said Montgomery and others like him deserve the opportunity for resentencing.

“They’ve matured in prison, they’ve grown up in prison. They’ve developed skills and opportunities that they can use in the community and many of them should have that right to get back into the community,” she said.

Duncan said after oral arguments that resentencing hearings would impose a significant burden on the states.

“It would make the state do a fact-intensive resentencing for thousands of offenders who are nonetheless facing a constitutionally valid sentence,” he said.

In the federal system and states that have decided Miller is retroactive, resentencing hearings already are underway.

In those states, judges have to consider the factors that the Supreme Court set out in Miller: including a juvenile’s age, home life, capacity to understand the criminal justice system and potential for rehabilitation.

Courts in 12 states have applied the Miller ruling retroactively: Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas and Wyoming. Courts in seven states have ruled otherwise: Alabama, Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana and Pennsylvania.

I sincerly agree that these children at the time when a crime was committed were just that children, why can’t they not be able too have a second chance? This is a very personal subject for me let me explain, my husband Terrance Lewis has been in jail for a crime that he did not commit, 18 long years he was 17 years old when this crime took place today 37 years old not too mention he was found innocent in federal court, he has an article from Innocent Project, innocent but still in prison. Co-defendence 2 sign statments went to court under oath, Terrance Lewis was not with them , now you tell me why my husband is still incarcerated for something he didn’t do, he don’t have a criminal record except for this case that the Honorable Judge Wells that sit on the bench in Federal Court of Pa, and she found him innocent ar his, PCRA, Hearing. My husband his family are seeking help. For more information , my email is, hakeemah1@yahoo, com