This story was reported and written by Halle Stockton for PublicSource.

It’s the end of the line for these Pennsylvania kids. They’ve fallen through every safety net, and they keep making the same mistakes or more violent ones.

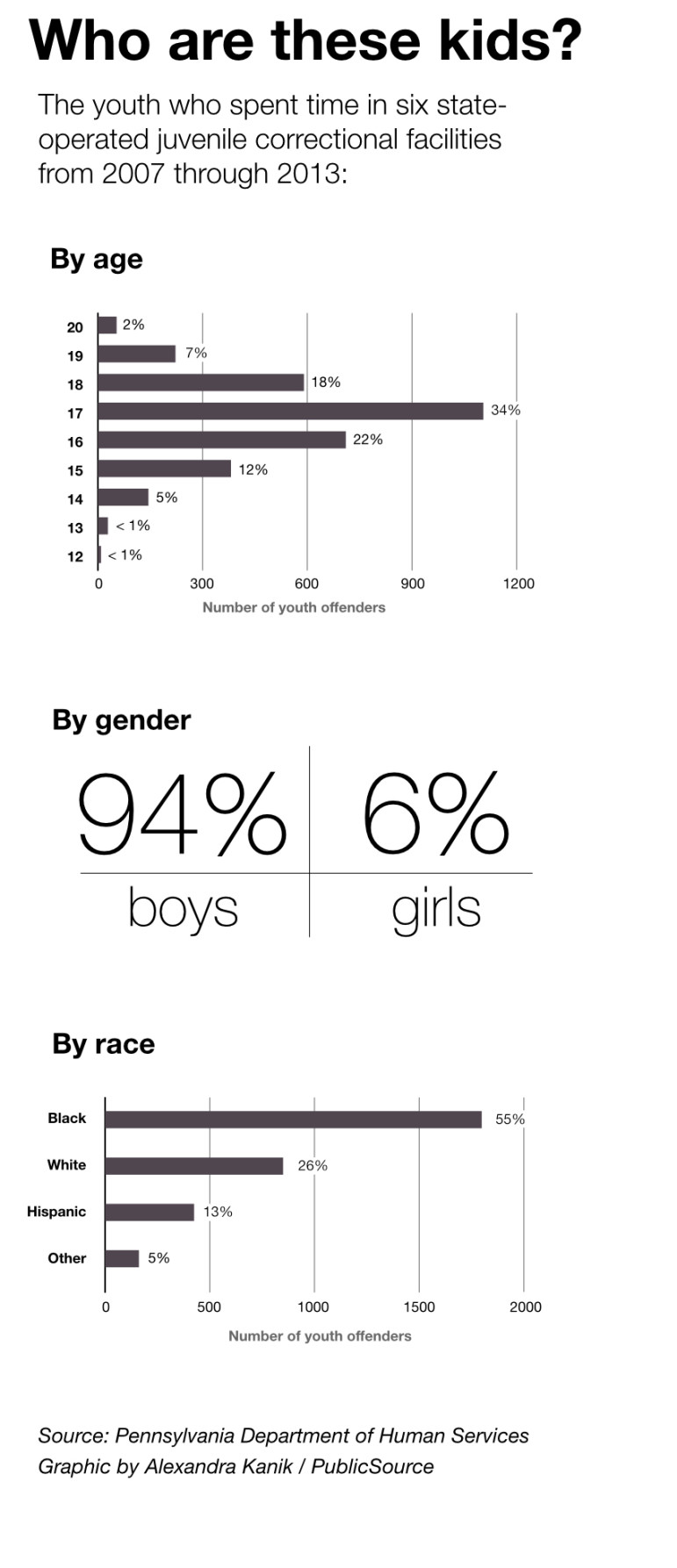

The kids — nearly all black or white teenage boys — are sent hours away from their families to youth correctional facilities, sterile lock-downs surrounded by barbed wire or cabins so far out in the wilderness they’re considered secure even without a fence.

They are the toughest kids in the juvenile justice system. And, in some ways, the most vulnerable.

In the months they spend at correctional facilities, they receive mood-altering psychiatric medications at strikingly high rates, particularly antipsychotic drugs that expose them to significant health risks.

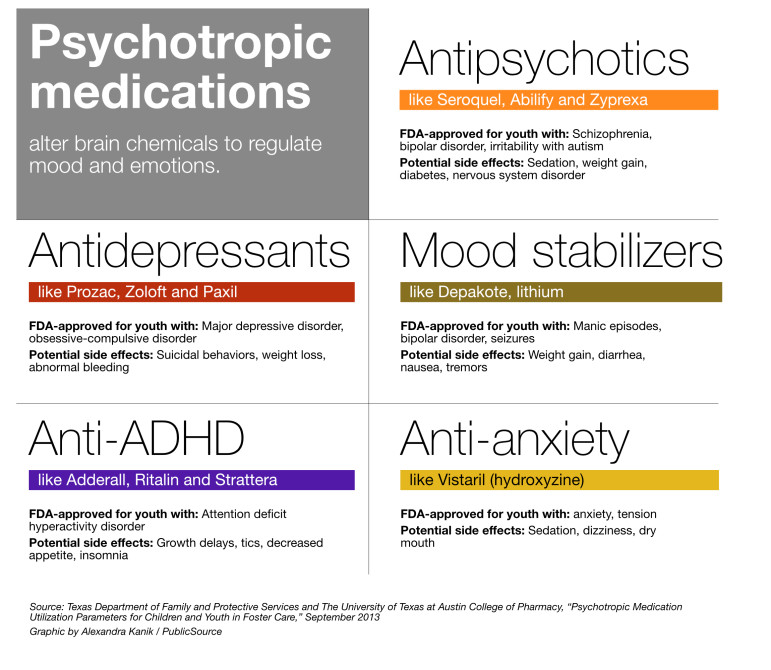

Psychiatric medications are prescribed to manage mental health and behavioral symptoms; antipsychotics are a type of psychiatric medicine approved to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and irritability with autism.

Kids are more vulnerable to the severe side effects of antipsychotics — rapid weight gain and diabetes among them — yet doctors and juvenile justice experts told PublicSource they’re confident the drugs are being used off-label in the state facilities to induce sleep or to reduce anxiety or aggression.

Some child advocates refer to this use as “chemical restraint.”

[Video: Julie Donohue: "Off-label prescribing is...]

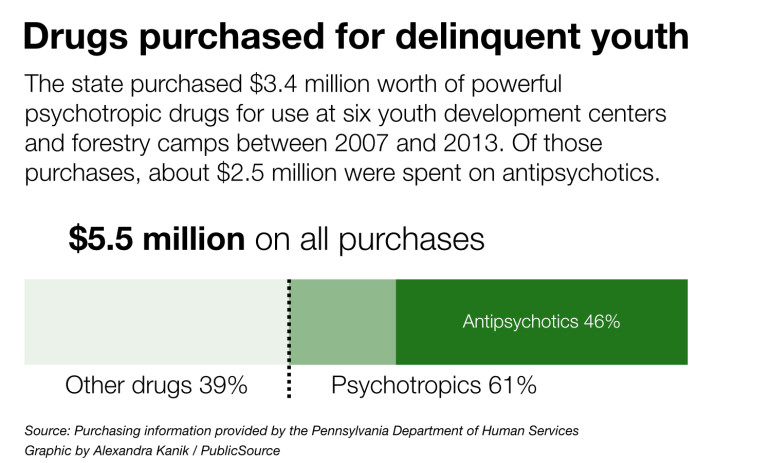

Over a seven-year period, enough antipsychotics were ordered to treat one-third of the confined youth, on average, at any given time, according to a PublicSource analysis of drug purchasing information obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, which operates the youth correctional facilities.

Only 1 to 2 percent of kids in the U.S. take antipsychotics.

Most “antipsychotic use is likely for sedation and behavioral control” in Pennsylvania’s youth correctional facilities, said Dr. Mark Olfson of the Columbia University Medical Center. Olfson is a leading research psychiatrist who reviewed the data PublicSource provided. “The new findings will hopefully spur much-needed institutional reforms.”

Thousands of at-risk kids lived in six state-operated youth development centers and forestry camps from 2007 through 2013. Within the razor wire — or dense tree lines in forestry camps — psychiatric medications are still flowing, despite the potential consequences to the developing brains and bodies of kids.

A recent study showed about one-fifth of foster care youth in Pennsylvania were taking antipsychotics in 2012 — a finding that sounded alarm bells for the Department of Human Services (DHS), which commissioned the report.

The secretary of the department called the rates among foster children “disturbing” and “unacceptable.”

The secretary of the department called the rates among foster children “disturbing” and “unacceptable.”

PublicSource’s look at the issue for the state’s most troubled delinquent young people showed even more widespread prescribing, yet Human Services officials said they aren’t encountering the same issues in the juvenile justice system.

The agency communicated with PublicSource almost entirely through email with responses approved by its legal department.

The department had weeks, and sometimes months, to respond to questions. Requests to interview DHS officials went unanswered for six weeks; an interview with Secretary Ted Dallas was scheduled and then abruptly cancelled. PublicSource shared its findings with the agency on Oct. 6.

The state also would not release the names of the doctors who are contracted to care for and prescribe to the youth, saying that it would compromise the safety of doctors if the facility residents had personal information on them.

A greater mental health need

Most of the kids are sent to the facilities after they’ve committed assaults, thefts and burglaries, or crimes related to guns and drugs. It is common for them to come from unstable homes or to roam with other kids who have had brushes with the law.

At its root, it is often a traumatic experience, one witnessed or committed, that drives their actions and can mimic mental illness.

At its root, it is often a traumatic experience, one witnessed or committed, that drives their actions and can mimic mental illness.

PublicSource was not granted access to the facilities — one of which closed on Sept. 30. The centers are described by those who have visited as plain, with more the feeling of a hospital than a jail, but still with a maze of locked doors.

The state juvenile justice system takes youth ages 10 to 21; the state facilities saw youth 12 and 20 in the seven years studied.

For an average of seven to eight months, they’re kept on a strict schedule for meals with schooling on the premises and some socializing in common areas with TVs and computers.

DHS spokeswoman Kait Gillis wrote in an email that the department provides individualized health care to the juveniles with a multidisciplinary team that regularly monitors the effects of psychiatric medications, also called psychotropics.

DHS spokeswoman Kait Gillis wrote in an email that the department provides individualized health care to the juveniles with a multidisciplinary team that regularly monitors the effects of psychiatric medications, also called psychotropics.

She wrote that 44 percent of 266 residents in the facilities on Sept. 30 had a psychotropic medication prescribed by a psychiatrist. The department conducted a manual calculation on that day shortly after receiving additional questions from PublicSource on the matter.

Many enter the facilities with a psychotropic prescription, Gillis added, and some can be weaned off as they make progress with other nondrug therapies.

“The protocols we have in place actually lead to a reduction or termination of medication when possible,” she wrote. However, the state did not share whether it has any policies or controls on prescribing.

The department could not say how many enter with such a prescription, and the invoices provided by the department did not link the medications to specific cases or diagnoses because of privacy concerns.

PublicSource consulted several health care professionals and researchers to review the data, which took two years to obtain and turn into a usable database.

While the experts did see red flags pointing to potentially excessive or inappropriate prescribing in the state facilities, justice-involved youth are known to have a greater mental health need than the general population. Studies and experts estimate that between 50 percent and 75 percent have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder.

However, not every disorder calls for a medication and certainly not an antipsychotic.

Psychiatric medications can quickly improve an adolescent's quality of life by alleviating depression or creating a clear mind. But many believe some prescribers overuse psychotropics, deploying them as a “silver bullet,” rather than addressing underlying issues.

“The great concern among children’s advocates is that ... too often the medications are used to the benefit of the institution to control behavior in ways that are not appropriate,” said Robert Schwartz, co-founder and recently retired executive director of the Juvenile Law Center, a national public-interest law firm based in Philadelphia that brought the notorious “Kids for Cash” scandal to light in 2008.

“The great concern among children’s advocates is that ... too often the medications are used to the benefit of the institution to control behavior in ways that are not appropriate,” said Robert Schwartz, co-founder and recently retired executive director of the Juvenile Law Center, a national public-interest law firm based in Philadelphia that brought the notorious “Kids for Cash” scandal to light in 2008.

The scandal netted two judges guilty of taking $2.6 million in kickbacks to send youth to private for-profit centers and created demand for reforms to policies affecting youth in the state’s juvenile courts. Tools were adopted in many counties to assess mental health upon arrival at juvenile justice facilities, and the state began unshackling kids in courtrooms.

Quick fix

Antipsychotics, the most used of the psychotropics in the state facilities, are extremely powerful and effective.

That’s why they’re used so often in crisis.

The drugs are tranquilizing, instilling a quick calm. Some equate that calm to a stupor.

Dr. Terry Lee, a child and adolescent psychiatrist who treats residents of a Washington state-run secure juvenile correctional facility, said most antipsychotics used in correctional facilities are given to control disruptive behavior, like outbursts, aggression and breaking the rules.

“There aren’t that many kids in juvenile justice facilities who are psychotic,” he said.

Judge Kathryn M. Hens-Greco, who has heard delinquency cases for five years in the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas, said she can’t remember ever sending a kid diagnosed with schizophrenia or autism to one of the state facilities.

Some youth with behavioral health disorders, Olfson said, are likely receiving antipsychotics inappropriately.

“If they have schizophrenia or bipolar, hopefully they are not here but in psychiatric hospitals getting rehabilitated,” he said. “I think their need for antipsychotics should make them ineligible for these facilities.”

The American Psychiatric Association says poor and minority kids are more likely to receive antipsychotics for off-label reasons. The PolicyLab, a research entity of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, found 5 percent of Medicaid-enrolled children in Pennsylvania were taking antipsychotics in 2012.

It was prescribing among the state’s Medicaid-enrolled foster children driving that rate.

Antipsychotics are quick to stabilize, but can also cause rapid weight gain that can lead to diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular problems. It may lead to brain shrinkage and a shorter lifespan.

Even the U.S. Supreme Court recognized that the brains of youth offenders are still developing when it took life sentences without parole off the table; so too, experts say, should state officials and doctors recognize they are taking a young person’s future into their hands when they prescribe psychotropics — for better or worse.

Dr. Christoph Correll, a psychiatrist and scientist, published a study in 2009 linking antipsychotic use and weight gain in youth. The kids studied gained 10 to 20 pounds in fewer than three months, he said. “Children and adolescents seem to be more vulnerable to these side effects,” he said. “We need to improve the behaviors of the mentally ill with education and healthy lifestyle and go to low-risk interventions first.

Gillis, the DHS spokeswoman, wrote that all residents of Pennsylvania youth correctional facilities get a mental-health screening within one hour of arrival. The kids are further assessed by social workers, nurses, physicians, psychological services associates, counselors and psychiatrists, she wrote.

Other therapies offered include cognitive behavioral therapy, individual and group counseling and programs for anger management and substance abuse issues, she wrote.

“There are unique challenges as many of the residents have not had consistent access to preventive care or to a medical provider,” Gillis wrote.

In the state facilities, the youth are provided a bill of rights, 22 liberties that include the rights to receive appropriate behavioral health care and to be free from excessive medication. The state contracts with the Mental Health Association in Pennsylvania to send in youth advocates. If medication questions come up, advocates refer them to a nurse.

Gillis wrote that kids prescribed certain psychiatric medications are monitored regularly through therapy, blood work and physical exams, and monthly updates are provided to the psychiatrist.

At the Washington state facility in which Lee works, he developed and implemented psychiatric practice guidelines. The guidelines include requirements to generally limit antipsychotic prescriptions to youth with psychotic and bipolar disorders; to prioritize skills training and nondrug therapy for disruptive behavior; and, when prescribing for sleep, to first use medications with more benign side effects, like melatonin or diphenhydramine (Benadryl).

Lee published a study on Oct. 1 in the journal Psychiatric Services that compared psychiatric medication costs and aggression levels at three secure juvenile facilities, including where he works.

The study, spanning 2003 to 2012, shows that Lee’s facility, with psychiatric practice guidelines, reduced its costs of psychotropic drugs by 26 percent, and incidents of aggression remained level. Costs for facilities without the guidelines doubled, and aggression levels increased, Lee said.

Psychotropic drugs dominated the medication budgets at the Pennsylvania youth centers, accounting for more than $3.4 million of the $5.5 million spent over seven years, according to the PublicSource analysis.

The state and counties pay for medications prescribed to residents of youth correctional facilities because Medicaid benefits are terminated or suspended when a juvenile is sent to one.

Seroquel (quetiapine) and Abilify (aripiprazole) — both antipsychotics — were two of the most ordered medications. About $2.2 million was spent on these two drugs alone.

(This interactive drug app will allow you to explore the data we received from the state.)

Rx pad

There has been no thorough examination in the state or nation on the prescribing of psychiatric medications to delinquent youth — an irony considering the momentous trend of jails and prisons, both adult and juvenile, filling the role of psychiatric facility.

With fewer resources and less training to cope with aggression, the mental health system over time has lost its ability to handle youthful offenders, and correctional facilities have become the default, said Ned Loughran, executive director of the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators.

“The Catch-22 is the more the youth correctional facilities respond to that and develop specialized programs because they have to deal with the youth, the more the courts are going to use them,” he said.

The majority of youth offenders in Pennsylvania are in private facilities. They are for the teens with lesser crimes, fewer problems and shorter stays. The chronic or violent offenders go to the youth development centers and forestry camps.

The facilities have adapted, contracting with medical professionals who know how to treat depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with medications that also fall under the umbrella of psychotropics.

In addition to antipsychotic use in the six state facilities:

- The antidepressants ordered were sufficient to treat more than 20 percent of the confined youth, on average, at any given time over the seven years studied. That includes the drugs Prozac and Paxil, which have been shown to increase suicidal behaviors in adolescents.

- Mood stabilizers, like lithium, which is generally used to treat manic episodes and bipolar disorder, were the next most used of the five drug classes analyzed. The prescriptions were sufficient to treat an average of 14 percent of residents at any given time.

- The four child and adolescent psychiatrists who advised PublicSource were surprised by the levels of anti-ADHD medications, which were ordered about one-third as often as antipsychotics. ADHD is likely one of the most prevalent disorders in the facilities, experts said. The orders were sufficient to treat an average of 9 percent of the youth at any given time.

- Medications to combat anxiety were the least ordered of all the psychotropic classes, sufficient to treat an average of 6 percent of the juveniles at any given time.

It is also possible that some juveniles receive more than one psychiatric medication. It’s called polypharmacy.

If one drug starts losing its power, the meds are often layered with others.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry says polypharmacy should be generally avoided.

Once a medication is on the market, a doctor has free rein to prescribe it for all kinds of symptoms. Sometimes the evidence supports its use, and sometimes not.

Correll, a professor at Hofstra University’s School of Medicine, advises using interventions with fewer side effects and rarely, if ever, trying antipsychotics off-label for sleeplessness, anxiety or ADHD. Alternatives can include anything from changing diet and sleep habits, to counseling, to other medication with fewer risks.

Finding clarity

Jennifer Drake is the national director of behavioral health services for Youth Advocate Programs (YAP), a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania-based nonprofit that provides community-based services to youth in 18 states and Washington, D.C., many of whom have been placed in corrections or foster care.

YAP has programs in 31 Pennsylvania counties and the city of Philadelphia.

Drake remembered a teenage boy who had experienced multiple placements, with medications layered at every stop.

When he returned home, YAP’s psychiatrist diagnosed him with depression. The boy was taken off antipsychotics and anti-ADHD drugs in favor of a mild antidepressant and counseling.

First, his headaches went away and he began to lose weight, she said. Then he started to break out of his shell and have conversations.

“I think all of us believe medication should only be one part of a child’s treatment,” Drake said. “They are certainly lifesaving and life-changing and many kids need them, but they shouldn't be the first line of treatment or the only treatment.”

(Read sidebar on how PublicSource got this story: Search for Data Began 2 Years Ago)

Coming Wednesday: Oversight of psychiatric meds for youth offenders lacking.

A George Polk Grant for Investigative Reporting and a grant from The Fund for Investigative Journalism helped to fund this PublicSource project.

PublicSource is a leading investigative news organization, providing Pennsylvania citizens with in-depth information. Reach Halle Stockton at 412-315-0263 or hstockton@publicsource.org. Follow her on Twitter at @HalleStockton.

Data work by Alexandra Kanik, Eric Holmberg and Stockton. App development by Kanik with help from the Institute for Nonprofit News. Graphics and charts by Kanik. Videos by Ryan Loew. Illustrations by Anita DuFalla.