Troubled kids, powerful drugs

[See Part 1: Pennsylvania Juvenile Offenders Given Psychiatric Drugs at High Rates]

[See Part 2: Where’s the oversight of psychiatric meds for Pennsylvania youth offenders?]

This story was reported and written by Halle Stockton for PublicSource.

Pennsylvania defied an Office of Open Records ruling and took the matter to court to conceal the names of doctors prescribing to kids confined in its six correctional facilities.

The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services insisted the physicians who care for and prescribe for the state’s most chronic or violent youth offenders would be endangered if their names were made public.

PublicSource requested the names of the doctors with whom the state contracts to determine their qualifications, disciplinary history and if they’re taking payments from drug companies.

PublicSource requested the names of the doctors with whom the state contracts to determine their qualifications, disciplinary history and if they’re taking payments from drug companies.

The request was part of a larger investigation that showed worrisome rates of psychiatric medications prescribed to the residents of the state’s secure youth development centers and forestry camps. Experts say the meds, some of which carry severe health risks, are being used to drug the kids into behaving.

The kids can be dangerous. Most who end up in the rural centers and camps have been in court time and time again. Many have handled guns and drugs; assaults and robberies are among the most common offenses.

But others who work with the same kind of kids found it troubling that there was so much concern over keeping the doctors anonymous.

Dr. Terry Lee, a child and adolescent psychiatrist to adjudicated delinquents in Washington state, said it’s not a good sign.

“Shouldn't it be public knowledge that public dollars are going to someone?” he said. “Shouldn’t you be able to track if they’ve had actions on their medical license?”

Lee also works in a secure juvenile correction facility, called the Echo Glen Children’s Center, about 30 miles outside Seattle.

“I’m not fearful. I tell people where I work,” he said. “They may have very good reasons, but it just doesn’t quite sound right.”

‘Detrimental’

The doctors are the “gateway” to medications. They also have a say in how long the kids, mostly teenagers, stay in the facilities.

Judges sometimes call on physicians and psychiatrists to evaluate their progress, and that can lead to either a release or waiting months before another review hearing.

The Department of Human Services (DHS), which operates the youth correctional facilities, said most doctors only use their last names during appointments with the juveniles.

The department would not release their full names because they say it would expose them and their families to the risk of physical harm.

“We have a major personal security issue with that,” DHS spokeswoman Kait Gillis said in a May 2014 phone call about the records requested. “The doctors disclose no personal information to these students. They receive a lot of threats on their physical safety. It would be really detrimental to them to have their personal information disclosed.”

The department repeatedly refused to share the names of the current doctors and psychiatrists, despite the state Office of Open Records ruling that they should be released.

The department repeatedly refused to share the names of the current doctors and psychiatrists, despite the state Office of Open Records ruling that they should be released.

The Open Records office wrote the department did not provide “evidence showing a nexus between the release of the doctors’ names and a risk of harm.”

It also pointed out that the names of public employees are generally part of the public record:

“Here, the doctors at issue receive taxpayer money to perform services for the department, and without disclosure of these names, taxpayers cannot find out the ultimate recipient of this money.”

The department petitioned the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania in February 2014 to review the Office of Open Records’ ruling. In June 2014, the court selected the case for mediation.

Before the mediation process could start, the department offered to redact pharmaceutical invoices it previously argued were not public record if PublicSource withdrew its request for doctors’ names.

PublicSource agreed to the compromise so that the project could move forward.

The invoices were used to analyze what prescriptions the kids were actually being given.

(This interactive drug app will allow you to explore the data we received from the state.)

The danger

The youth residents were described as threatening, retaliatory and manipulative by the department and doctors.

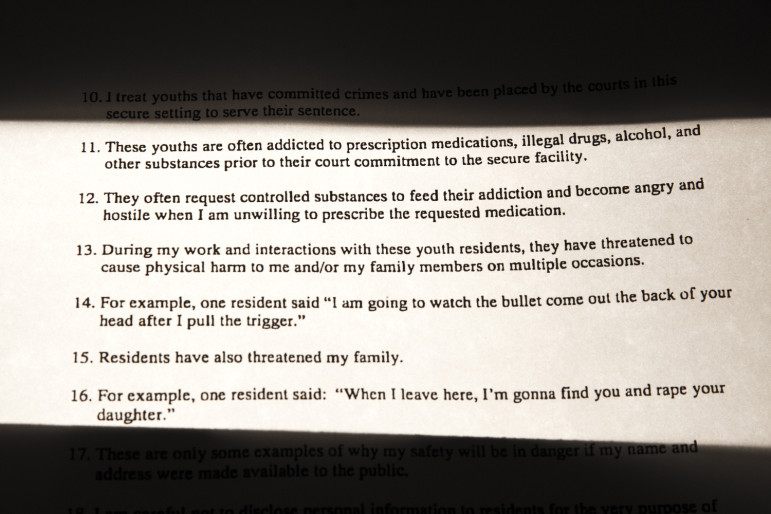

One physician who had worked in one of the facilities for three years at the time said he fears his name being released to the media would lead to the troubled teens, their family members and gang associates being able to learn his full name and home and office address.

“Because many such persons have violent proclivities, my personal security and the personal security of my family and my neighbors would be placed in heightened jeopardy,” according to the doctor’s affidavit.

The doctor said residents have threatened to rape his daughter and to shoot him.

Natasha Khan/PublicSource

An excerpt of a doctor's affidavit submitted by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services in open-records correspondence.

The physicians attributed substance-abuse issues among the youth as a point of tension. According to affidavits, the residents often request controlled substances and get hostile or make false complaints when denied.

Another clinician, who has done this work for 12 years, wrote: ”The youths are observant and attempt to find out personal information to use against me and my co-workers.”

The affidavits were submitted to the Open Records office by DHS with the doctors’ names redacted, and the state declined all requests for interviews.

Advanced Correctional Healthcare provides medical services at adult and youth facilities in 17 Midwestern states. Deborah Ash, vice president of compliance, said their doctors also only share their title and last name for safety reasons.

“It is still fairly easy to find them even with just a last name,” she said, “but you do the best you can do short of changing your name.”

The company also discourages the use of doctor-specific parking spots to prevent inmates’ families or gang associates on the outside from tracking them down.

Residents of the Pennsylvania facilities have proven to be dangerous at times.

In 2011, three teenagers were charged with attacking a guard at the South Mountain Secure Treatment Unit, according to a Public Opinion article.

According to The Daily Item, a resident of the North Central Secure Treatment Unit in October 2014 punched a staff member after a search of his room; the young man pleaded guilty to the assault in February.

Six staff members were injured in what was called a riot, started by four residents at the Cresson Secure Treatment Unit on Jan. 1, 2015, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

PublicSource could not locate any accounts of incidents specifically targeting medical staff, and the department did not identify any in their arguments.

Prescribing pressures

Doctors taking money from drug companies is an inherent conflict of interest, especially when doctors are treating vulnerable kids in institutions where parental consent isn’t always obtained.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act established a federal rule that pharmaceutical companies must disclose what gifts, speaker fees and other payments doctors receive from them.

In Florida, the Palm Beach Post found that one in three psychiatrists contracted by the Department of Juvenile Justice over five years — 2007 to 2011 — had taken speaker fees or received gifts from pharmaceutical companies.

There was at least one obvious instance of a doctor who increased the prescribing of a certain medication at the same time he was paid by the maker of the drug.

The reporters were able to assess this because of Florida’s broad public records law.

Amanda Fortuna, a spokeswoman for the Florida department, told PublicSource that although a list of the doctors is not readily available, their names would not be exempt from the public record.

Pennsylvania doctors received about $143 million from drug and medical device companies from August 2013 to December 2014; only five states had doctors taking more money, according to ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs app.

Meredith Matone, a research scientist for PolicyLab at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said the prescribing habits of individual doctors isn’t a driving factor in the overall issue of psychotropic medication use.

“There’s a small portion of providers who are probably skewed for their own personal gain,” she said.

For most prescribers, she said, they simply use the medications more once they are educated about them. “They may just look at it as another tool in their toolbox.”

But who’s supervising how they use those tools?

Gail Wasserman, a child psychologist who directs the Center for the Promotion of Mental Health in Juvenile Justice in New York, said it can be particularly challenging to supervise doctors who are contracted to provide services.

“Health care [has] got to have its own supervisory structure,” she said. “Where is that, who does that and how do you make sure it works and it’s accountable?”

The Department of Human Services did not answer several questions posed by PublicSource on the checks and balances for its doctors.

‘The right to know me’

As a judge who has dealt with delinquent youth face to face for more than five years, Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas Judge Kathryn M. Hens-Greco could not relate to the doctors’ fears.

“Well, I would say the youth know my name pretty clearly. It’s on the bench. It’s on the order,” she said. “I don't spend a lot of time worrying about my personal safety. I pay attention a little, but they have the right to know me. I am the one sending them to where they’re going.”

Hens-Greco said she is bothered that the doctors’ names were not released. She could only surmise that it is difficult to attract psychiatrists to the rural facilities, and the state felt they must honor their wish to remain anonymous to retain their services.

[Video: Doctors in short supply]

Sidney Ornduff, a psychologist in the Memphis area, evaluated hundreds of kids annually as director of clinical services for the Juvenile Court of Memphis and Shelby County for nearly five years.

She was torn when she heard about the state’s decision to withhold the doctors’ names. She said she has been threatened and scared by delinquent youth and their families before. She also said she felt the public has a right to know if the doctors are qualified and in good standing with their professional boards.

“Safety first, yes, but a degree of transparency,” she said.

The importance placed on the anonymity of the psychiatrists was upsetting to Dr. Melisa Rowland, a child and adolescent psychiatrist who is working with New York City’s juvenile justice system to implement multisystemic therapy, a model that works with chronically violent youth within their homes and communities.

“If they really feel that way, that’s probably part of the problem,” she said. “One thing that drives me crazy in my field is they act like they’re sociopaths. I’ve just worked with so many hundreds and hundreds of these kids … I can’t remember the last time I came across a kid that was scary.”

A George Polk Grant for Investigative Reporting and a grant from The Fund for Investigative Journalism helped fund this PublicSource project.

Reach Halle Stockton at 412-315-0263 or hstockton@publicsource.org. Follow her on Twitter at @HalleStockton.

Illustration by Anita Dufalla and video by Ryan Loew.

The doctors are in fear but not for the reasons they state, they are in fear of being exposed. Working in a profession that is supposed to Rehabilitate troubled youth, were you not expecting hurdles, did you not expect to helping youth to overcome obstacles, counsel them, provide the care they need and deserve? The answer is no, they are only interested in a paycheck and probably could not get hired anywhere else. The doctors have a right to know who they are treating but children do not have a right to know their doctor? We are holding the children accountable for thier actions now lets extend that same responsibility to the doctors treating them. Lead by example!!!