During a session with a student at Spokane’s North Central High School, truancy board members Macy Pate and Justin Mauger listen intently as the teen explains why he was missing school. Pate is a counselor at the school. Mauger works for the local YMCA. (Steve Ringman / The Seattle Times)

SPOKANE, Washington — Christine Ellenwood hid the first two letters from her Spokane high school last fall, warning her that skipping class was against the law.

She was living with her older brother and didn’t want him to know she had missed so much school that she risked juvenile detention for herself and possible fines for him. But she couldn’t hide from her school.

The day after she received the second letter, the 16-year-old was summoned into a classroom to face her counselor and a roomful of strangers, called together as part of one of the most successful truancy-prevention efforts in the state.

They told her they were there to help, not punish her, but they needed to know why she wasn’t showing up until second or third period most mornings.

She started crying.

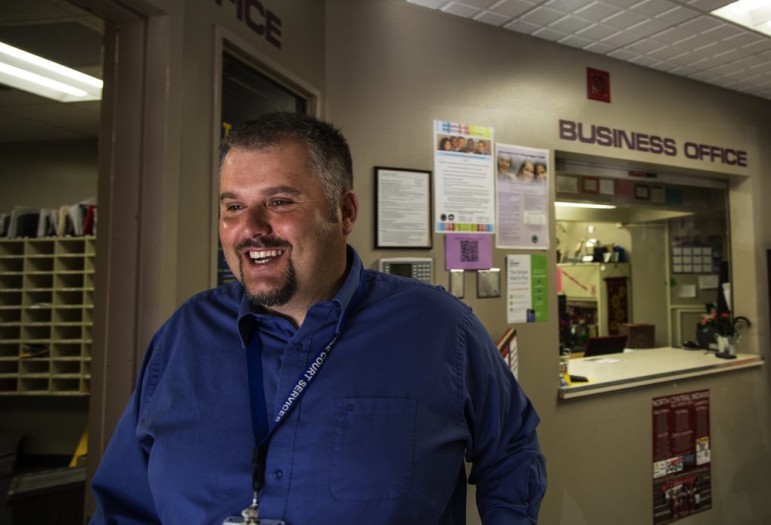

Martin Kolodrub, a bearish-looking man with cropped salt-and-pepper hair, followed up on a hunch based on years of experience.

“Do you have to take care of your siblings?” he asked.

Christine looked down, too scared to meet his eyes, but answered yes, revealing her long-held secret.

She’d never told anyone at school that she cooked breakfast for her younger brother and sister, got them dressed, fixed her sister’s hair, waited until her brother climbed aboard his bus for kindergarten and then rode the city bus with her sister to preschool.

In Spokane, a collaboration of schools, the court and the community is designed to tackle the root causes of truancy. Here, a student, a principal and a truancy specialist discuss what they’ve learned. (Steve Ringman / The Seattle Times)

Kolodrub’s question finally made her realize she was in over her head — and she wasn’t alone.

The adults in the room, officially known as the school’s community truancy board, started with a simple but important step: rearranging her schedule so she could start later in the morning.

The board — a collaboration of the school, the courts and community organizations — is designed to tackle the root causes of truancy, the goal behind a 20-year-old state law requiring school districts to take legal action when kids miss too many days.

But 70 percent of the state’s 295 school districts don’t have such boards — or any other truancy program — to provide that help. They simply send kids to court for a stern lecture and the threat of detention, an approach most agree has failed.

One study, done for the state Supreme Court, found that only 15 percent of Washington students sent to court for truancy graduate on time. A second, also done for the court this year, said just one-third of such students graduate or earn a GED.

But the results in Spokane County are much better, especially in the West Valley School District, which has helped as many as 82 percent of truant students earn a diploma or GED.

That’s what inspired Ellenwood’s school district — Spokane Public Schools — to start its own board.

Other counties, including King County, also have found some success with group workshops, also designed to keep kids out of court.

But West Valley’s approach has produced the best results to date, inspiring not just Spokane, but other districts to try truancy boards, too, including a recent push to launch them in eight districts in Pierce County.

The boards are not easy to do well.

Highline abandoned one after two years when grant money ran out. Seattle tried a few boards in the late 1990s, but the district also ran out of money and momentum.

Community truancy boards require strong cooperation between schools, courts and community groups — and passionate advocates such as Kolodrub, who was so important to West Valley’s success that researchers call his contributions “the Martin effect.”

But West Valley shows that they can be worth the money. Although a 2013 study showed that two Spokane boards (the one in West Valley and another at one Spokane high school) cost about $200,000 per year, it also found that they saved taxpayers as much as $68 million — the estimated price of lost tax revenues and increased social services associated with dropouts.

Weekly community truancy board hearings are held for students at Spokane’s North Central High School. The board ‐ a collaboration of the school, the court and community organizations — is designed to tackle the root causes of truancy. (Steve Ringman / The Seattle Times)

Becca Law

Before 1995, school districts seldom involved the juvenile courts in truancy cases.

That’s the year the Legislature passed the Becca Law, named after Rebecca Hedman, a 13-year-old Tacoma girl who ran away from home and was found murdered in Spokane.

Skipping school wasn’t the main focus of the law, which gave parents the right to commit runaway children to counseling centers against their will.

Yet because chronic truancy often predicts later trouble, the Becca Law also requires districts to send students and their families to court if students rack up seven unexcused absences in a single month or 10 in a year.

The idea was that the threat of juvenile detention for kids and fines for parents would send a stronger message to families than just another visit to the principal’s office.

From the beginning, the law recommended truancy boards as a way to help solve kids’ underlying problems without sending them to court.

But 20 years later, only 51 school districts have them — even with strong evidence of what good they can do.

[Related: What Science, Common Sense Tell Us About Kids and the Law]

A 2000 legislative report, for example, found that in Seattle Public Schools, sending truant students to court had no effect on whether those students remained in school.

That’s not encouraging, given how many truancy cases the state’s courts now handle — about 11,300 a year, nearly equal to all other juvenile-court cases combined.

And for reasons not well understood, that caseload reflects only about a third of the students whose chronic absences warrant court involvement.

West Valley, with nearly 4,000 students, was one of the first in the state to create a truancy board composed of educators, school counselors and parent volunteers.

They quickly learned that the stereotype of the truant who thumbs his nose at school fit very few of the students they met.

Marcia Glenn, who tracks truancy full time for the district, still remembers one boy who, back in the board’s first year in 1996, stayed home because his mother’s boyfriend wouldn’t beat her if the fifth-grader was home.

With its initial boards, West Valley was able to keep a third of its chronically truant students out of court by drawing up contracts with them and their parents, with the promise that they wouldn’t have to go to court if they fulfilled them.

Then in 2004, the district persuaded social-service agencies, churches, job programs and other organizations to join the board, too, so they could offer help.

With that change, 80 percent of the district’s chronically truant students never ended up in courtrooms.

But the district didn’t stop there. They wanted to reach the last 20 percent, too, and decided they needed an ambassador from the court system to work with kids day to day.

That guy turned out to be Martin Kolodrub.

Martin Kolodrub, who oversees truancy programs for Spokane County Juvenile Court, spends much of his time in the field at kids’ homes, schools, truancy board hearings and in court. (Steve Ringman / The Seattle Times)

Soft spot for underdogs

Kolodrub started out at West Valley’s Spokane Valley High School in 2007, after the Spokane Juvenile Court received a grant from the MacArthur Foundation to study whether West Valley’s truancy board was working as well it seemed.

Principal Larry Bush agreed to be part of the study, but he wanted something in return — a court-paid specialist to work in his school and others in the district to help make sure that kids followed through on the plans spelled out at the community truancy board.

His partner in that deal also happened to be his wife, Bonnie Bush, the court administrator.

She chose Kolodrub for the job, a probation officer with a passion for helping such kids — the plain-spoken son of a construction worker who grew up in one of Spokane’s poorest neighborhoods and had a soft spot for underdogs.

First, Kolodrub had to overcome years of mutual distrust between the school system and the judicial system.

He stepped on a lot of toes as he learned how the school operated, finding out the hard way which teachers would let him take students out of class to talk, for example.

“It was an extremely uncomfortable first three or four months for me,” he said.

But he eventually won over teachers and students, using a system to make sure he checked in with the right kids at the right time. He asked them detailed questions about their lives so he could get them the right support, and he went to bat for them with teachers and principals when they needed an ally.

“I didn’t sell myself,” he said. “The kids I worked with sold me to their friends.”

He also helped kids out of embarrassing situations that kept them out of class, like the teen he noticed wearing ratty shoes held together with duct tape. By that time, Kolodrub was carrying sneakers in the trunk of his car, along with lice kits and other supplies.

For some students, that kind of support made Kolodrub the one adult at school they didn’t want to disappoint.

“Kids used to come to me and say: Martin, I did this for you,” he said. “Here I am, some schmuck working for the government and I’ve got somebody telling me that. That was the best feeling ever.”

National model

With Kolodrub working in West Valley’s schools, the number of truant students that West Valley sent to court dropped from 20 percent to about 6 percent, which has held fairly steady since 2012, when the grant money ran out and Kolodrub returned to juvenile court.

Other districts in the juvenile court’s jurisdiction — including Mead and Spokane public schools — have since started their own community truancy boards.

The MacArthur Foundation promotes West Valley as a national model, and local officials developed a step-by-step guide after they were swamped by calls from all over the country asking how they did it.

One question is whether the success in West Valley can be achieved elsewhere without “the Martin effect.” Larry Bush says he could go into any district in the state and find someone who could be a “Martin.” Kolodrub agrees.

“I didn’t do anything that was rocket science,” he said. “I treated kids like individuals and I helped them with their individual needs.”

One recent fall morning, Kolodrub observed the community truancy board at North Central High School — the same one where he had helped turn Christine Ellenwood’s life around the year before.

Nathan Hall was there with his 16-year-old son.

The board’s members challenged some of the son’s excuses for missing school, like his hypothesis that he might have been poisoned by the nacho sauce he ate in a food class.

But they could see that he was bright enough to pursue his dream of becoming an entrepreneur and one of the board members told him about a YMCA after-school program that could help him improve his algebra grades.

Kolodrub said later that the teen was a fence-walker — a smart guy who could go either way — his favorite kind of kid to help.

Earlier that morning, out in the hall, Kolodrub saw Ellenwood and gave her a hug.

She had once been on the fence, too.

But after six difficult months away from her family at a Bremerton military school her counselor told her about, she was back at North Central for her senior year, on track for graduation.

“I want to go to school,” she said. “I want to finish school. I want to go into the military. I want to be a nurse.”

John Higgins: 206-464-3145 or jhiggins@seattletimes.com. On Twitter @jhigginsST

This story originally appeared in The Seattle Times.

Education Lab is a project of The Seattle Times that spotlights promising approaches to persistent challenges in public education.

More related articles:

Collaboration Seeks to Divert Kids from Juvenile Justice System

Cops in Schools Need Special Training About Children and Trauma