It’s been 2½ years since Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal signed a landmark overhaul of Georgia’s juvenile justice system into law. The measure has resulted in a sharp drop in commitments to the state’s youth correctional system and is expected to save tens of millions of dollars by replacing incarceration with community supervision.

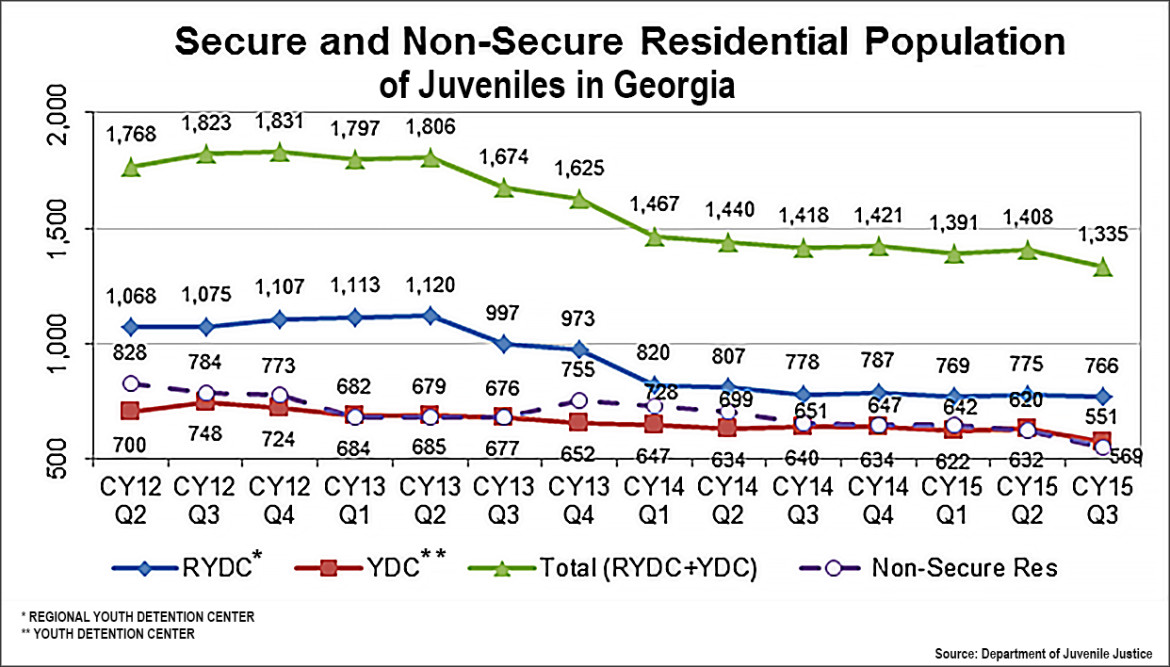

It’s too early for comprehensive recidivism numbers. But the state Department of Juvenile Justice says commitments to state facilities are down 20 percent since the law took effect — and it won’t need to build two new facilities that had been projected before the reforms.

JJIE recently caught up with Deal to talk about how things are going so far, whether he plans to revisit some of Georgia’s more controversial practices and why he sees education as the next piece of the puzzle to be solved.

NOTE: Some answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Q. You’re getting good reviews for your juvenile justice reforms. How do you think it’s going so far?

A. I think it’s a remarkable success. Quite honestly, we’ve seen the success in a shorter time frame than I had originally anticipated.

We started on the adult side, focused on adults that were coming into our prison system but were being classified as nonviolent. We decided we could divert many of those nonviolent offenders into accountability courts — the drug courts, DUI courts, increasingly mental health courts and more recently veterans’ courts. And that’s been a huge success. In excess of 4,000 individuals in the first quarter of last year were in accountability courts across our state, and the number of those courts continue to grow, and we’re glad to see that. ...

The second year was juvenile justice reform. It was modeled after the adult program, but by the very distinction of being juveniles, it had to be done a little differently.

We approached it by identifying the counties that were sending the largest number of juveniles into our juvenile justice system, and we did it on a grant program. Those counties became eligible for the first round of grants to put in place local alternative diversion programs, and since that time, in the budget, we have expanded the money, and we have continued to expand that across the state. It’s more difficult to do in our more rural, outlying areas of Georgia, but nevertheless the problems are there just as they are elsewhere.

We think that has been very successful ... Participating counties have seen felony commitments and placements in short-term programs drop 62 percent over a nine-month period. As a result, we’ve been able to close two juvenile detention centers. So that is a money-saving aspect of it, but we’re plowing that money into creating more of these local alternatives.

Q. The original projections were this program could save up to $85 million. How are actual results tracking with those projections?

A. I don’t have the dollar numbers on that, but when you see a 62 percent drop in incarceration — and when you consider that for a juvenile, the cost of one year of incarceration is in excess of $90,000 — it doesn’t take long for that to add up to a substantial sum of money. We’ll have more accurate figures by the end of next year. I would think that because the very nature of juvenile detention is sometimes short-term, it’s fluctuating. We’ll have a better feel for it next year.

Q. What’s been the biggest obstacle to implementation? Is there any part of the system you need to give a swift kick to get it turning?

A. Quite honestly, we’ve had very good response from the local communities, because it does require the local communities to be willing to participate in these alternative diversion programs. No matter what you do in criminal justice reform, when you are talking about alternatives to incarceration, you have to overcome the potential fear of the local community that their safety is being jeopardized. I think we have shown that is not the case in the local arena, and I believe these numbers that we’re seeing are also demonstrating that you are just as safe if not safer to have alternative programs in the juvenile arena as well.

Two other things have happened, and these are somewhat new. One is called the Georgia Preparatory Academy. They are focused on trying to award GEDs and technical certificates to juveniles who will be in our youth development centers. Back in May of this year, they had a graduation ceremony. They had 53 diplomas and GEDs and technical college certificates that were awarded to young people who were in pretty much all of our youth development centers across the state. That’s something I think we have to continue to focus on. Education is the one ingredient that is not only the most common denominator in the adult population, it‘s also the most common denominator in our juvenile population. Many if not most of the juveniles have either been kicked out of school, they’ve been suspended — some of them suspended indefinitely — or they were of the age where they just simply dropped out. The lack of education, the lack of skills, is the common denominator.

Another thing is the Annie E. Casey Foundation has awarded grants to our state. These work on a county-by-county basis, and it’s to try to encourage alternatives for low-risk juvenile offenders as we do in the adult population. We have two counties now that participate in it, and that’s Clayton and Rockdale counties ... Because Clayton County was involved in the program earlier, they adopted the initiative in 2003, and we’re told it resulted in an 80 percent decrease in the average daily population and less than 1 percent of county’s youth felony offenders were rearrested on a felony charge. Those are rather remarkable statistics. If we can replicate that with the use of the Annie E. Casey Foundation around the state, that will truly be phenomenal.

Q. Are there any counties or particular regions that have taken to these reforms more aggressively than others?

A. As far as I can tell most all of them have taken on the approach very successfully. As I said, the first year, because we didn’t have sufficient funds to do it all across the state, we identified the counties that were sending us the largest number of juveniles into the system. As you can imagine, those are the metro areas of state — the greater Atlanta area, Columbus, Augusta, Savannah, et cetera. In the more recent year, we have spread those grants out across the state, so we’re gradually moving them out to try to cover our entire state.

Q. How much money are we talking about going to things like raises? Are you having to hire more probation officers to handle more community supervision? Can you give me some way of quantifying that?

A. We put a slight pay raise in last year’s budget. Most of the time, pay raises, because they are across the board, are reflected in general budgets. That will be something we hope we can address in the upcoming budget in the next session of the General Assembly. But it will be an across-the-board type approach.

Q. So out of that projected $85 million, you don’t have a number for how much has been put back into the system so far?

A. I don’t at this point, because it’s an ongoing thing.

[Related: Cops in Schools Need Special Training About Children and Trauma]

Q. You were a juvenile judge at one point. How has that experience influenced this process for you? Is there any one case or set of kids that informed your thinking as you went ahead?

A. The most frustrating thing as a juvenile court judge was I pretty much had only two options for a young person that was in trouble that came before the court. One was to simply send them into the juvenile system, which was generally not a good alternative except in the most extreme cases. The other was to send them home, to the environment where they got in trouble in the first place, with very little assistance in terms of additional personnel other than a probation officer. That’s what we’ve tried to remedy on the reform side. We’ve given the juvenile judges more options. They’re not put in a posture of either something that may be considered too extreme or something that may be inappropriate. They have more options in their arsenal for dealing with these young people. I suppose that was the biggest thing. It was not a specific case, it was the overall context in which juvenile judges were having to operate.

Q. Recidivism is the big number that everybody looks at, but is there any other metric you look to as an indicator of success?

A. I would say it is the programs I’ve talked about here of improving their skill levels, their educational levels. That’s something that is very difficult to do, because most of them come into the system, I’ve been told, as much as three to four years behind where they should be, agewise, in terms of their skills. So it’s a very intensive, almost one-on-one type of approach to improve their educational skills. And by the very nature of the short term of duration in facilities, it has to be very concentrated. We’re trying to improve the ability to have those educational opportunities extended to the juveniles after they leave maybe a detention facility and move back into supervised probation. We have some programs that we’re working on that we think will allow us to do that, but it’s very difficult ... We have to work on ways in which we can accommodate them in which we can further their educational opportunities. That’s why these quasi-educational approaches, I think, are so important.

Q. Recently, the Casey Foundation came out with a call to phase out the last of the large, secure youth facilities. Is that something your administration is willing to take on that this point?

A. That’s a tough question. We have to always remember that any reform we have to put in place must have as its first priority keeping the public safe. We have juveniles now who are committing very serious crimes, and they may or may not, depending on the prosecuting attorneys, be treated as an adult for purposes of prosecution. And our law requires that if they are not of age, even if they’re convicted of the adult offense, they are still incarcerated in our juvenile facilities. We have to have facilities to handle that population group, because you’ve got everything from murderers right on down the line, even though by age they’re still classified as juveniles.

I don’t think you could ever totally do away with those kind of detention facilities. But can we provide better alternatives for those who do not have offenses of that high a caliber? Yes, and that is our goal That’s what we are continually working on.

Q. You just had a situation here where the state just had to pay out about $4 million in settlements to kids who were beaten up by one kid held at Eastman [Regional Youth Detention Center]. If you want to keep those facilities open, what do have you do to improve safety and avoid those kind of payouts?

A. That is an isolated incident, but it is a serious isolated incident. My personal thought is someone who is that dangerous is not appropriately housed in a juvenile facility. We don’t have the same kind of constraint alternatives for someone who’s classified as a juvenile. But if he’s a threat to the general population, which this individual has indicated on multiple occasions that he is, we have to be able to separate that person away from the general population. That sounds more like an adult situation, where you can confine them in solitary. We don’t have the same degree of latitude with the detention of juveniles.

That is an area which, in light of this case, that we’re going to have to take a serious look at. How do we balance the safety of the other young people who are in the system with the requirement to confine someone who’s classified as a juvenile, but who’s much more dangerous than the average population? That’s not an easy answer to come by.

Q. There have been periodic calls to revisit Senate Bill 440, the “Seven Deadly Sins” law that prosecutes kids as adults. You’ve got situations where people are doing long stretches in adult prisons for crimes they committed when they were 15 or 16. As you go forward, any plans to revisit that?

A. That may be an area that the Criminal Justice Reform commission may decide to look at. We hope we can keep them as an ongoing reviewing body. We‘ve already made some modifications, as you know, to revisit eligibility for adult offenders, to reclassify some of them in terms of parole eligibility. This is probably an area of that is of a similar nature. I don’t know whether the reform commission is currently looking at that, but it may be something they choose to look at.

Q. But it’s not a priority for you at this point?

A. Not at this point, because those that fit that definition are some of the most violent offenders we have, even though they may be of a young age.

Q. You’ve said your plan for opportunity schools is going to be the next piece of this. Louisiana’s model, which a lot of this is drawn from, has had its successes, but it’s also had its drawbacks. A lot of people have said they’ve played with the numbers to hit the marks they have. In your plan, how do you insulate it from that kind of criticism? What kind of steps do you have to keep that from happening?

A. In Louisiana, you had the hurricane, and the hurricane virtually demolished the entire school system in New Orleans, so they were able to start from scratch. Arguably, the New Orleans school system before the hurricane was one of the worst school systems in the entire country ... so their successes and their failures should be measured in light of where they were before they came in with what they call their Recovery School District. I think by that kind of measurement, they have been successful. I have personally visited there. We took a group of legislators and other interested people there last year. What we saw and what we heard was, ‘Yes, we’ve had some difficulties, but overall we’re making significant progress.’ When you take the worst of the worst, progress is sometimes very slow. But I was impressed with the attitude we saw from the administrators, from the teachers, and it appeared that they were much better than they were before the reforms. And I think that’s what we always look for.

Why is the Opportunity School District so important for Georgia? With almost seven out of 10 adults in our prison system having dropped out of school, the likelihood that a child going to chronically failing school is going to likewise fail and drop out are significantly increased from the regular school population. There is a direct linkage between lack of education and presence in a prison, and the crimes that go on between those points in time in a person’s life have many victims and cost everybody a lot of money, grief and heartache. The reason I call it the ultimate criminal justice reform is if you can get at the root, the most common denominator in criminal conduct — the lack of an education, the lack of a marketable skill — and you can remove those elements, then the likelihood of reducing your juvenile detention population and your adult criminal population are significantly enhanced.

Q. But you don’t have to look far. Atlanta had its own cheating scandal. There have been questions raised about how many kids really transfer or drop out. You have seen some of the same questions raised in New Orleans. Is there any extra effort in there to ensure the integrity of the numbers you’re using to base the system on?

A. I don’t think many people are arguing the accuracy of the numbers as to whether or not the schools are failing. That’s not in dispute ... I can’t take on reform of the education community in terms of the adults. I can only try to reform the processes under which they work. If somebody’s going to cheat, whether they be a student or they be a teacher, there’s very little that you can legislatively do to prevent that.

More related articles:

Senate Judiciary Approves Criminal Justice Bill with Juvenile Provisions

House Committee Hears Strong Calls for JJDPA Reauthorization

I am a member of the Governors Task Force on Reentry and have been involved since 2012. I have witnessed very little progress. I truly believe the Governor and his administration are talking in the right direction and that some of these successes are measurable but there are difficulties in implementing programs that are not being addressed. I am a volunteer adult GED administrator and instructor at a pilot mens’ Transitional Center. I volunteered to set up the GED program after hearing that the facility did not have a GED program and had not had one in five years. It took more than a year to hold the first class. I have four men ready to test who have not ever had a computer based class. The computers are available but still have glitches that must be sorted out and we are still awaiting calculators as well. My complaints are handled cordially then nothing happens. Internal barriers simply override any and most if not all attempts to organize any consistent program. There is hope however if the administration is willing to consider unconventional solutions such as extending the GED program into the work force, hiring me or someone who could devote the time required to make the program successful and connecting work to education. This is only an example of a solutions based approach.