“Every interaction between police officers and our young people is, or can be, an opportunity for prevention or intervention.”

– Betsy Hodges, Minneapolis mayor

Laura E. Furr

Is there ever a “good” youth arrest? Even without the use of excessive force, arrest can prove traumatic and destructive and the effects long lasting. One police leader from a small Pennsylvania town recounted the story of a young person who lost his promising future, with a merit-based scholarship to a four-year college, when police arrested him and charged him with a curfew violation. He spent no time in a detention center, but his criminal record, even for a status offense, lost him his scholarship and college acceptance. Imagine how this story would have ended if the arresting officer had had a way to correct the behavior without formally charging this youth.

Heidi Cooper

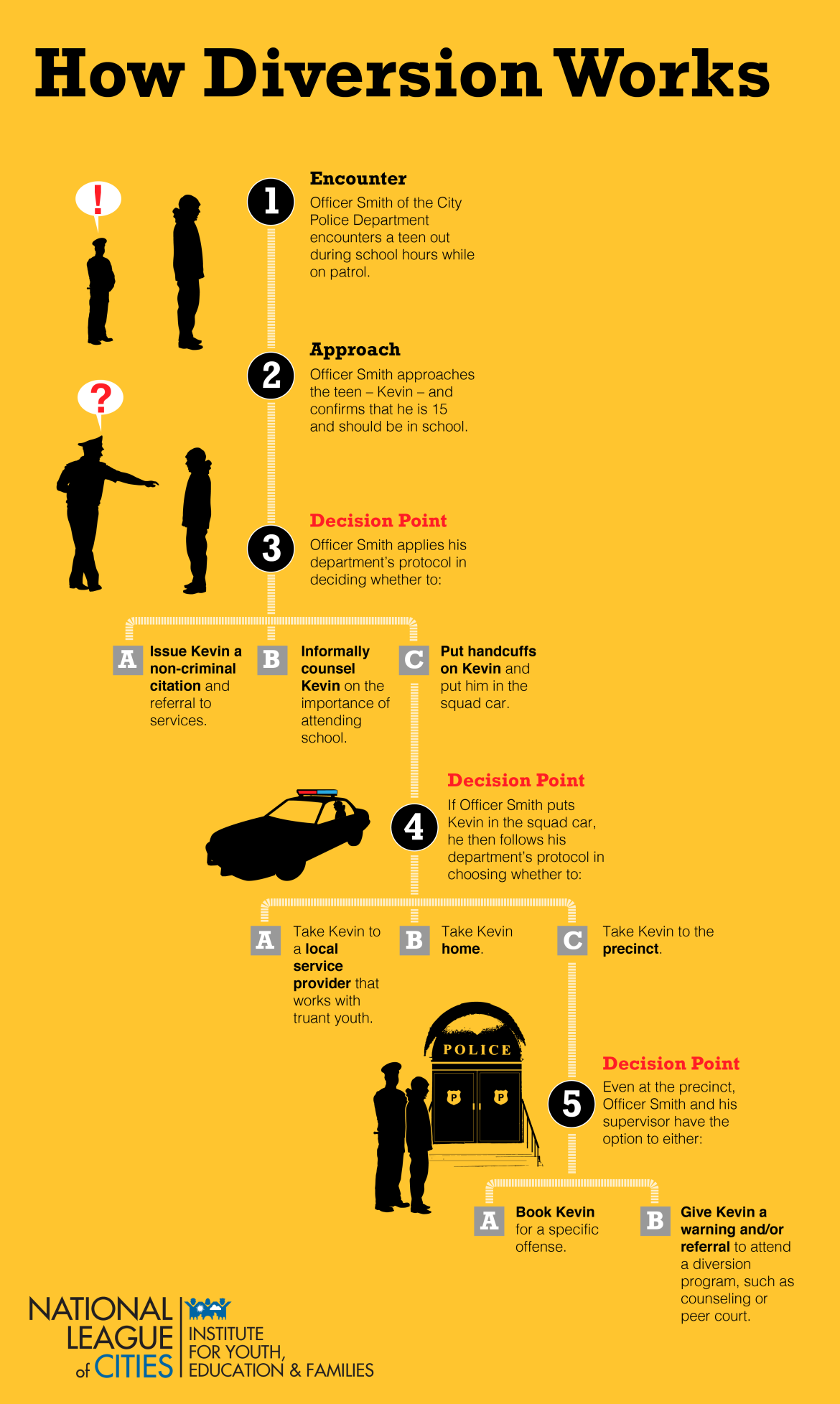

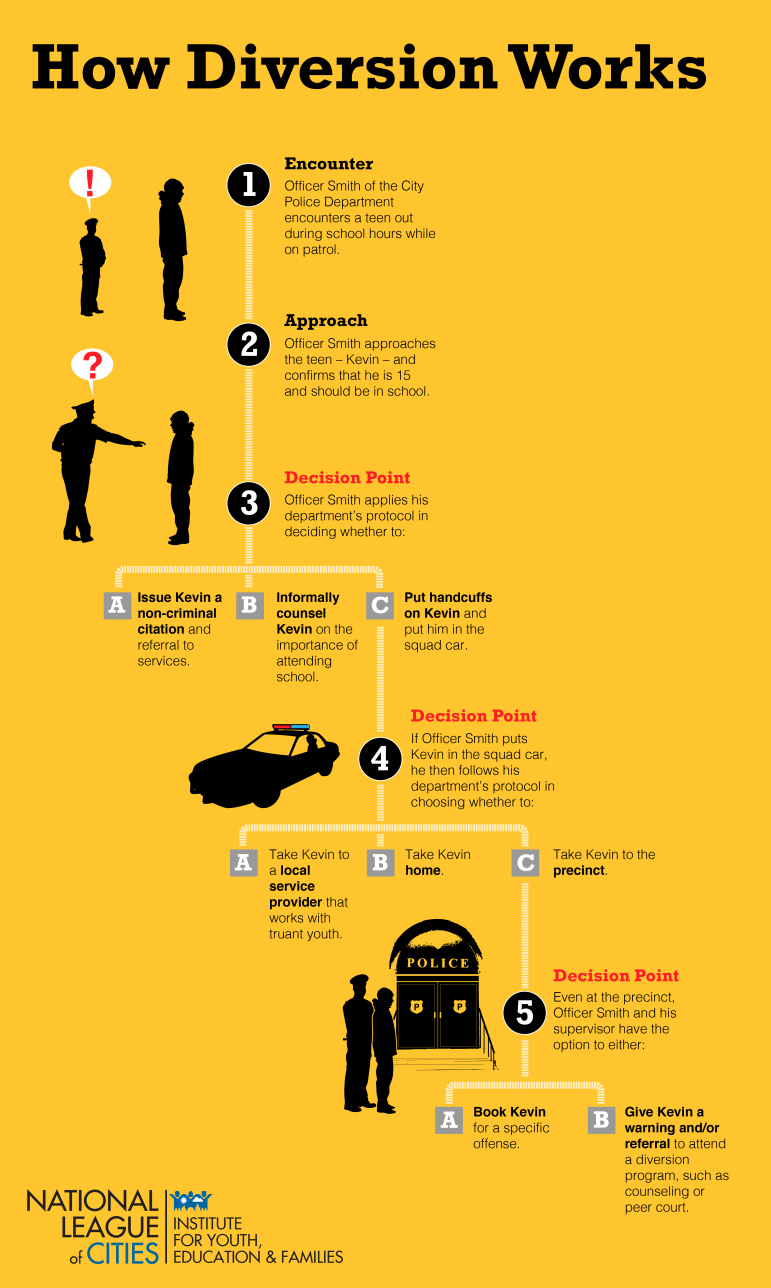

In response to data showing large increases in arrests in schools, the persistence of racial disparities among arrested youth and the devastating impact of justice involvement, city leaders have developed high-impact, developmentally appropriate responses to bad behavior. The National League of Cities’ Alternatives to Arrest for Young People issue brief uncovered three key trends in juvenile justice reform: the development of early or prebooking diversion programs, the implementation of assessments and objective criteria for decision-making and enhanced officer training.

In Philadelphia, former Mayor Michael Nutter’s public safety agenda focused on community-police relationships and using data to inform policy decisions. After recognizing through data analysis a disparate impact of school arrests on youth of color, the city developed a new policy regarding school arrests.

Under the policy, in effect for the past year, the Philadelphia Police Department no longer arrests youth, or removes them from school, for disorderly conduct or certain possession charges. Families of these youth receive follow-up from specially trained school resource officers (SRO) and neighborhood-based service providers who help develop a plan to help that young person get back on track. A crucial component of the effort involves what does not happen — youth diverted from arrest through this policy don’t receive a charge, even if they fail to complete services.

Mayors in Nashville, Tennessee, and Minneapolis supported diversion toward community-based services through budgets and policy reforms. In both cities, police take youth to juvenile assessment and service centers instead of detention intake units. At these centers, youth receive assessments and referrals to appropriate services. These programs provide a significant benefit for police departments as well. Rather than taking hours for a police officer to process a youth through more typical systems, dropping a youth off at juvenile assessment and service centers often takes mere minutes.

For diversion programs to be fair, law officers must base inclusion on objective criteria such as type of offense. While staff at detention facilities have been using risk assessments at intake for some time, a new partnership between National Youth Screening and Assessment Partners at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and the police department in Brookline, Massachusetts, is working on adapting existing tools for use at arrest. Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have validated the accuracy of assessments by the Massachusetts Arrest Screening Tool for Law Enforcement in multiple Massachusetts police departments. The Brookline Police Department and others are now piloting the tools as part of a comprehensive juvenile diversion program.

For maximum effectiveness, officers should receive training on content such as risk assessment, as well as the rationale for any reform approach. Resource organizations within the Models for Change partnership have developed a new cadre of training curricula. Among others, the Mental Health and Juvenile Justice Collaborative for Change has begun piloting its new Adolescent Mental Health Training for SROs (AMHT-SRO) in diverse departments across the country. The training seeks to support SROs to develop the critical skills and capacity for appropriately responding to the many predictable behavior issues that they often encounter among adolescents with mental health conditions.

[Related: West Virginia Eases Strict Truancy Law]

The new diversion and training models have produced promising early results. However, currently, too few youth have access to these alternatives and the effects of bad policy and practices is in the news on a daily basis. Policy experts, practitioners and advocates will continue to work together to make progress toward reforms in the face of tremendous inertia and measured successes, and continue to develop even more new, evidence-informed efforts.

Program success highlights

Philadelphia: Ninety percent of referred youth completed services with community providers, and school-based arrests have dropped 60 percent. Assaults on law enforcement officers in schools have dropped 18 percent.

Lake Charles, Louisiana: Since the foundation of the Multi-Agency Resource Center, no youth have received referrals to placement for status offenses.

Nashville, Tennessee: Former Mayor Karl Dean’s initiative, the Metro Student Attendance Center, provides services for youth who would have otherwise been charged with truancy or loitering during school hours. Since its formation, truancy has dropped 47 percent.

Laura E. Furr is the senior associate for juvenile justice reform in the National League of Cities’ Institute for Youth, Education, and Families. Heidi Cooper is the justice reform associate in NLC’s Institute for Youth, Education and Families. Follow Heidi on Twitter @hcoopercomenetz.

More related articles:

NCJJ Report Shows Juvenile Crime Keeps Falling, But Reasons Elusive

Baltimore’s Newly Approved Youth Curfew among Strictest in Nation

In Class, Out of Court: How One School District Triumphed Over Truancy