Photos by Karen Savage

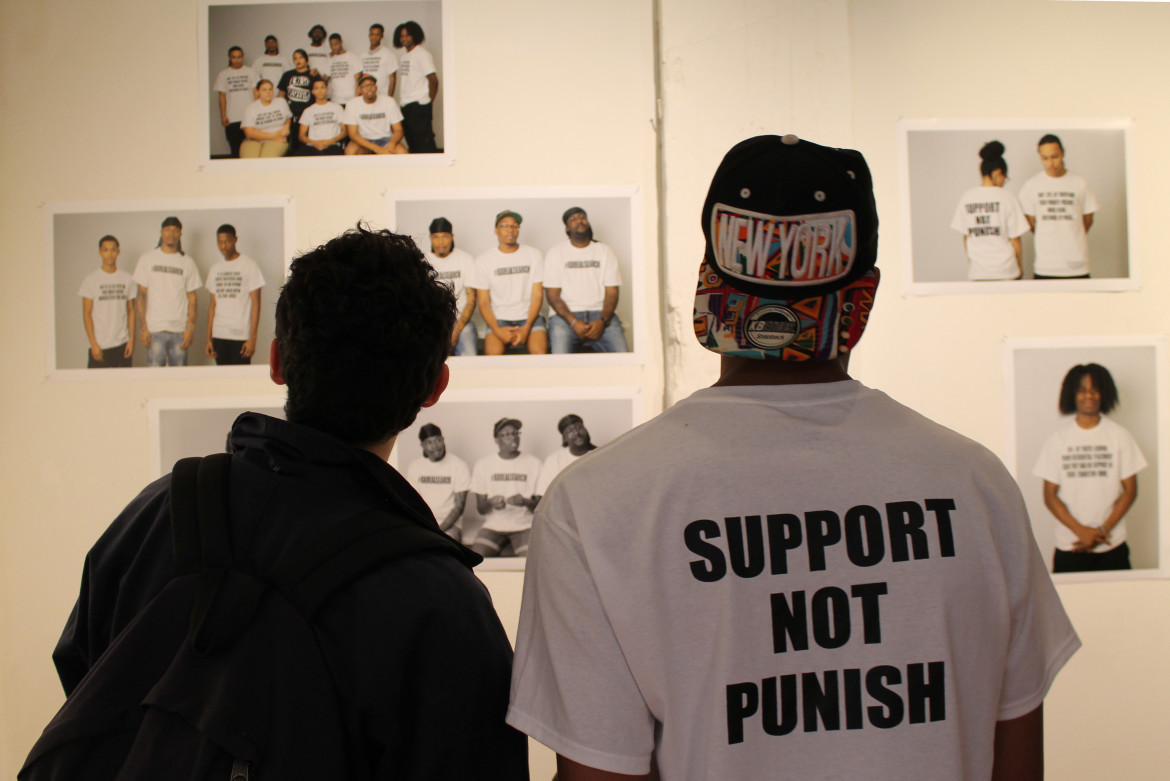

Survey researcher DeVante Lewis (right) views portraits of local youth wearing shirts that highlight the report's main findings at the Bronx Art Space.

NEW YORK — The bold black lettering stood out emphatically on freshly pressed white T-shirts.

One read, “Only 28 percent of youth had their parents present while being questioned by police.”

“Only 42 percent of the youth had their parents notified immediately after arrest,” read another.

The T-shirts were a concrete way to dramatize a survey about some of the most pressing juvenile justice issues in the Bronx. Unusually, young adults from the community had been trained in participatory action research, which is created for, about and by affected community members.

Wearing the shirts, they eagerly shared their personal experiences with about 100 neighborhood residents and some experts at a February event.

The commissioner for the Administration for Children’s Services, which provides juvenile justice services in New York City, said she was impressed not only with the survey but with the suggested solutions.

The commissioner for the Administration for Children’s Services, which provides juvenile justice services in New York City, said she was impressed not only with the survey but with the suggested solutions.

“Send me your recommendations, you should hold me accountable,” Gladys Carrion said. “I am responsible. You pay my salary.”

A New York Police Department (NYPD) spokesperson, in an emailed statement, declined to respond to the survey findings, but said it is department policy to notify parents or guardians when juveniles are taken into custody and to question juveniles in their presence.

The report the youths created, “Support Not Punish: A Participatory Action Research Report” outlines findings from a survey created and completed over 18 months during 2014 and 2015.

It showed that nearly 80 percent of youth arrested miss more than 20 days of school following an arrest, and 45 percent said the programs they were sent to were not helpful. The report contains sections on arrest, probation, juvenile court processes, detention, placement and family member support.

But the research was about more than just identifying problems.

“The best type of research doesn’t just tell us what is, but it helps us imagine what could be,” said Whitney Richards-Calathes, who trained the group and works on juvenile justice reform in Los Angeles, during the panel discussion.

“The best type of research doesn’t just tell us what is, but it helps us imagine what could be,” said Whitney Richards-Calathes, who trained the group and works on juvenile justice reform in Los Angeles, during the panel discussion.

“We want to know what does a world look like where 10-year-olds aren’t being arrested,” she said.

Additionally, researchers found 37 percent felt police used excessive force and 75 percent said they felt officers were being dishonest regarding what would happen after their arrest.

“In situations like this,” said researcher DeVante Lewis, 24, “solutions are simple. You just don’t question a kid without their parent.”

Wesley Jennings, associate professor of criminology at the University of South Florida, who has also published research on youth in Puerto Rico and the Bronx, agreed.

“Relocation of a youth, for any reason, you would hope that parent or guardian would be abreast of that in real time,” he said, adding that although it differs from traditional academic research, “Support Not Punish” is valuable because it comes solely from the community and addresses the entire juvenile justice process.

Attorney Ezekiel Edwards, with the American Civil Liberties Union, said the bigger issue is the overcriminalization and overincarceration of the black and minority community in New York and the nation.

“Just think about that — a 10-year-old getting arrested,” he said. “You should call the parents. But why are you arresting a 10-year-old?”

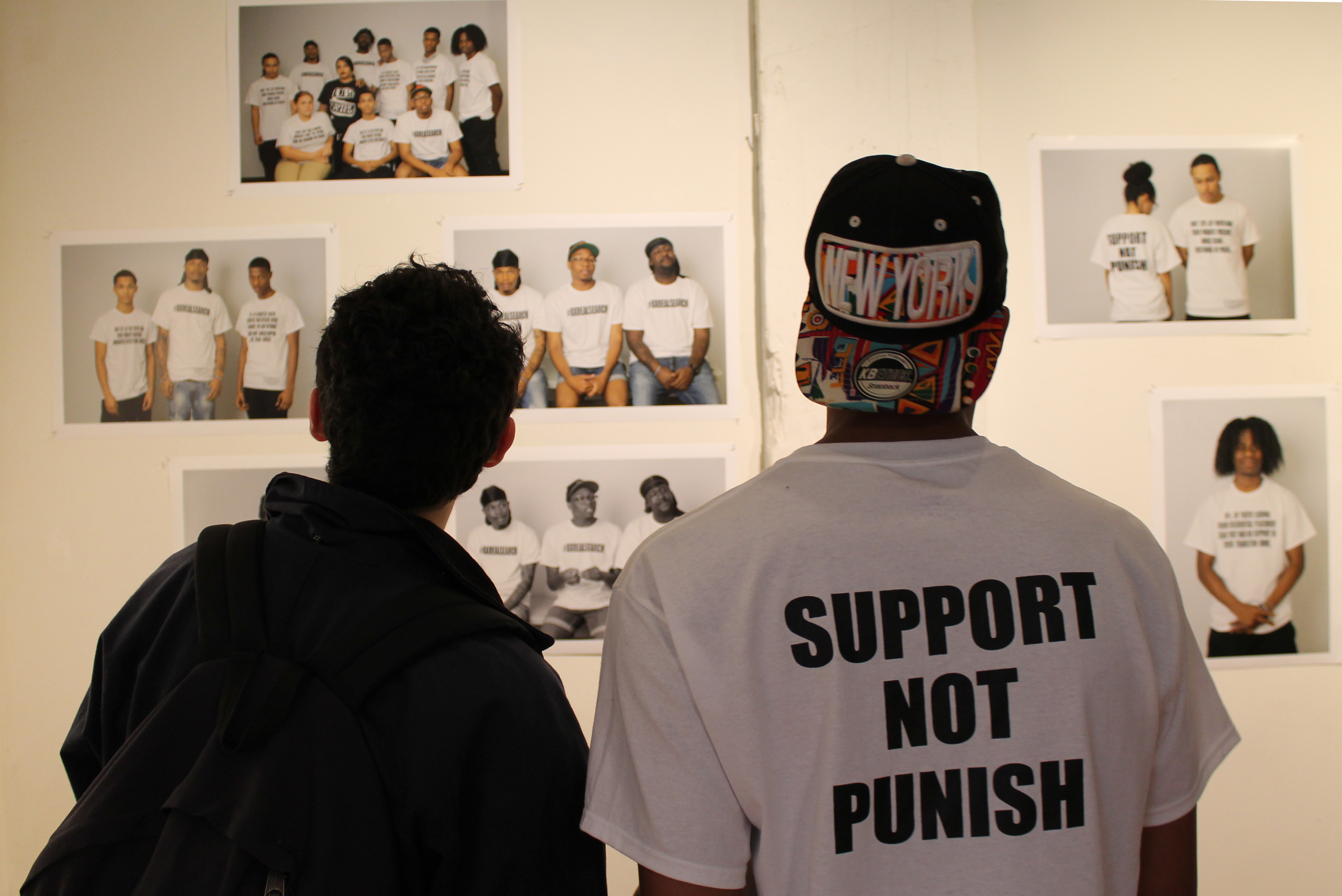

Report co-authors Charles Hudgins (right) and DeVante Lewis (back to camera) explain its findings at the Bronx Art Space.

What Lewis said he found especially appalling was that among those surveyed, 70 percent said their parents weren’t notified immediately following their arrest, which is a violation of New York state law.

The team was pleasantly surprised that 62 percent of the juveniles surveyed found their probation officers to be helpful, said researcher Charles Hudgins, 25.

The team spent a week learning about data collection and about three weeks creating, testing and tweaking the survey, Lewis said. Then they hit the streets, surveying 92 youth under the age of 15 by attending family court, holding focus groups and going to block parties in Bronx neighborhoods. Researchers sought out youth on playgrounds and in shopping areas like the intersection of Third Avenue and 149th Street.

The tense atmosphere in family court made data collection the most difficult, Hudgins said. “What we learned is that youth are willing to share when they are in a safe environment with people they trust,” he said.

[Related: Racial, Ethnic Disparities Stubbornly Endure in Juvenile Justice System, Expert Says]

Not long after completing the report, Lewis was coming home late and dozed off on a near-empty D train. He said he was jolted wide awake by two officers standing over him who violently dragged him off the train and told him to remove his shoes. His pockets were searched repeatedly.

“In the back of my head, I was thinking of this report that I just got done finishing and thinking if I was 12, I’d be going through the same thing,” he said.

“But at that moment when I had two police officers push me against the wall and physically search me, I wanted my mother,” he said, reminding the audience he was an adult at the time.

The survey was a project of Community Connections for Youth, a nonprofit that works to develop community-based alternatives to incarceration for young people.

Seventy percent of those surveyed would like to be involved in policy discussions, Lewis said. He suggested community gatherings such as the presentation are an important part of that process.

“It’s so important to share our stories,” he said. “There’s strength in knowing that you’re not the only one and that there are others who look like me who are also victimized and criminalized by the system.”

More related stories:

Proposed Georgia Budget Shifts Money to Community Programs

Advocates Offer Solutions for Kids at Crossroads of School, Justice System