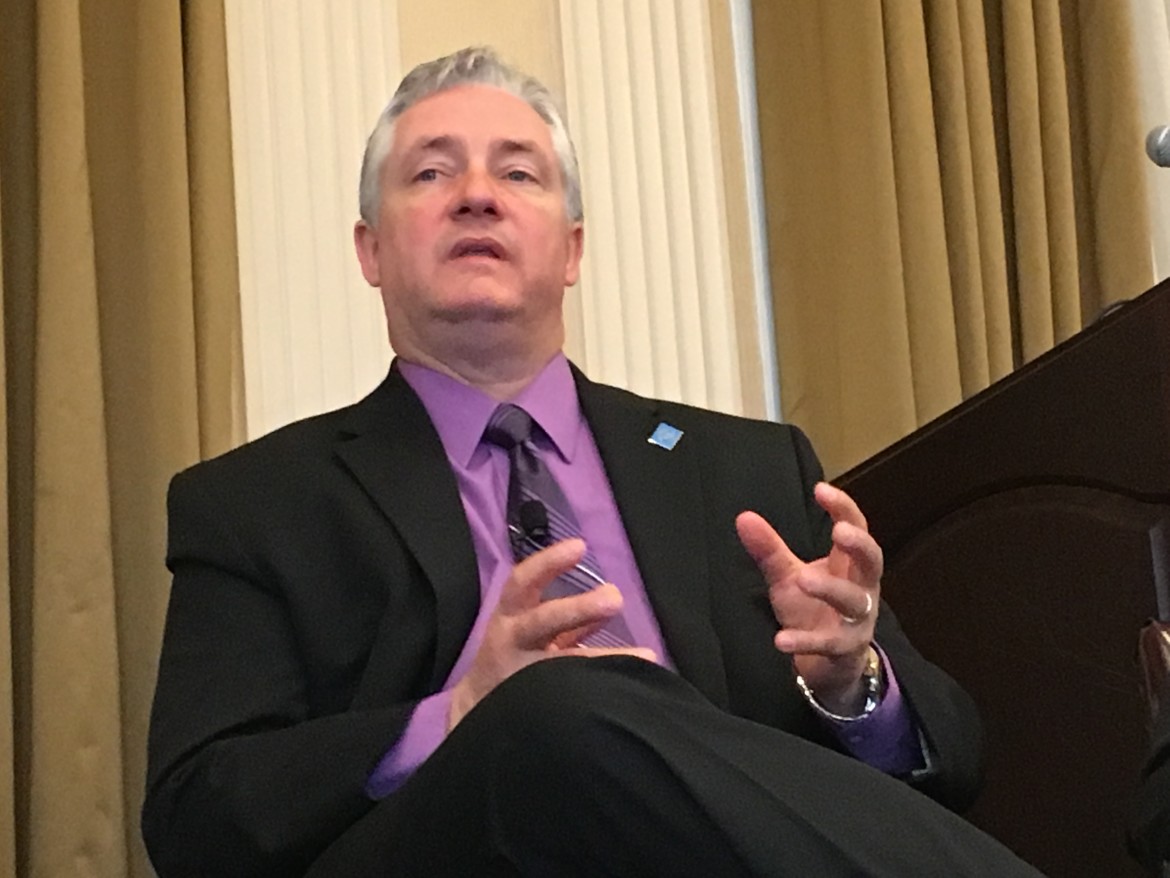

Photos by Daryl Khan

Roy L. Juncker Jr., director of the Department of Juvenile Services in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, had an "ah-ha moment" about how well the juvenile justice system works more than 10 years ago.

BOSTON — The revelation struck Roy L. Juncker Jr. more than a decade ago, but the memory remains as stark as it is vivid.

Juncker was standing outside the detention facility in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, about seven months into his tenure as director of juvenile services there. He was having a chat with Nat Williams, the facility’s supervisor.

Williams interrupted the talk to say hello to a middle-aged black woman and her daughter heading toward the entrance. Williams knew the women by name, Juncker said. Williams told his boss that one woman was the grandmother, the other the mother, and they were going to visit their daughter and granddaughter, both of whom were in detention.

“I looked at him and I said: So you’re telling me that we have had three generations of this family cycle through our detention center, and he said yes,” Juncker recalled. “I said we are doing something wrong here. Why is that that we have three generations of a family coming through our detention center and we have not broken that cycle?”

Juncker resolved then, outside the detention center, to spearhead an effort to reform how he did business for the youth coming into his system.

“That was kind of my ah-ha moment,” he said. “I thought, my God, we have to do something different. I mean this is insanity; we are doing the same thing over and over again looking for a change in the families, so at that point I realized we had to do something different.”

Juncker was not alone in being haunted by his professional past, and dogged by old decisions. Many of the professionals who gathered for the symposium on probation system reform organized by the RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice in Boston in April talked about the lingering guilt they still wrestle with today.

Juncker was not alone in being haunted by his professional past, and dogged by old decisions. Many of the professionals who gathered for the symposium on probation system reform organized by the RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice in Boston in April talked about the lingering guilt they still wrestle with today.

Many of the men and women on the frontlines of the juvenile justice systems, especially those in leadership positions, have made great strides in reforming their jurisdictions, pointing to lower recidivism, staggering drops in the number of youth in secure facilities and lower caseloads.

But despite such successes, there was a theme that was palpable over the week of the symposium, both privately in hotel hallways and publicly from the podium: a desire to make up for past mistakes. The more they implemented sound reforms that led to better outcomes for the children in their care, the more they thought about the old way of doing things and the damage they may have caused.

“I’d like to tell everybody here that I was some kind of great visionary that saw the future of juvenile justice, that I designed my own program and moved forward, but that would be too far from the truth to sell that to you,” said Bob Bermingham, the director of court services in Fairfax County (Virginia) Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court. “I did all the wrong things for the right reasons for about 15 or 16 years of my career. I think about the possible harm that I did to kids and families over the course of my career. There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t use that to motivate me.”

Fairfax is a safe, affluent community with a low crime rate, he said. But after he took over as director of the county agency he found the detention centers were filled to maximum capacity, his probation officers’ caseloads were stunningly high, and the system was rife with disproportionate minority representation.

Fairfax is a safe, affluent community with a low crime rate, he said. But after he took over as director of the county agency he found the detention centers were filled to maximum capacity, his probation officers’ caseloads were stunningly high, and the system was rife with disproportionate minority representation.

“It didn’t make sense,” he said. “It motivated me to go out and look at what was going on around the country.”

Adolphus Graves, the chief probation officer of Fulton County Juvenile Court in Atlanta.

Adolphus Graves, the chief probation officer of Fulton CountyJuvenile Court in Atlanta, was also driven to transform his juvenile justice system by the mistakes he made as a young probation officer.

“I was a little wayward and misguided as a probation officer,” he said. “Knowing my times as a probation officer, and how many things I did horribly, or how many children that I irresponsibly, or sometimes just ignorantly, subjected to detention because I had no other tools,” he added. “The recurring theme consistently has been the lack of knowledge, of understanding what’s going on, the depth of what’s going on in a child’s life.”

When Keith Snyder started his career as a probation officer he remembers how many of the youth in his caseload were afflicted with mental health problems. Now, as executive director of Pennsylvania’s Juvenile Court Judges’ Commission, he has worked to change that.

“The quality and quantity of mental health services just wasn’t good and that was still stuck in my craw,” he said.

A decade ago, when the opportunity to work on reforming the system in Pennsylvania presented itself, he said, he volunteered to step up and spearhead the reform.

Gina Vincent is associate professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Gina Vincent said she remembers researching as a graduate student outcomes for youth in the juvenile justice system and making troubling discoveries about recidivism rates and the number of youth in detention facilities. She is an associate professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts, and the president of National Youth Screening and Assessment Partners,

“And that was in tree-hugging Canada,” she said. “We have come a long way, but we still have a long way to go.”

There is an 18-inch by 24-inch framed autographed drawing of Spider-Man that reminds John Tuell about what he describes as the moral underpinning of the work he and other probation professionals do. It was drawn by Eduardo, a youth he worked with when he was an administrator at a residential treatment facility for chronic delinquent offenders in Fairfax, Virginia.

John Tuell is the executive director of the RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice.

Tuell, the executive director of the RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, lived in the area where he worked, so he would occasionally run into young people at a ballgame or at their jobs. He saw Eduardo at a favorite restaurant. He was a youth with a childhood marred by poverty and abuse. Now he was working at a restaurant and going to college to become a cartoonist.

“His brief note accompanying that autograph remains a priceless reminder for me of why we must give our all to these youth; more, why we must succeed, he said.

Not all the stories ended so well. Tuell worked with Christy, a bright young woman with a broken childhood, when she was 14 to 18. She looked to him as a father figure, he said. So it was a blow when Christy’s sister told him Christy had killed herself shortly after her 26th birthday.

“Her loss and my realizations of the many gaps and failures in my approach coupled with the way our systems responded to Christy, drive me every day to prevent another of these stories,” he said.

Juncker has more than a past as a probation officer driving him. Before he joined probation, he was a police officer. He worked as a juvenile detective for more than four years.

“As a police officer we looked for probable cause, we made arrests, we put kids into the system because that’s what we were trained to do,” he said. “Once I made the arrest and the child went to court and was adjudicated I didn’t care what happened to that child.”

Now as a leader transforming his agency Juncker said he feels he can atone for that jaded approach to children.

“I felt like all the damage I had done before arresting these kids and putting them in the system, that now I had an opportunity to correct that and make positive changes.”

This story has been updated.

This article doesn’t make clear the transgressions that these officials felt they’d committed. One assumes they are talking in part about the eagerness with which juvenile corrections adopted the “superpredator” nonsense in the ’90s.