Photos by Daryl Khan

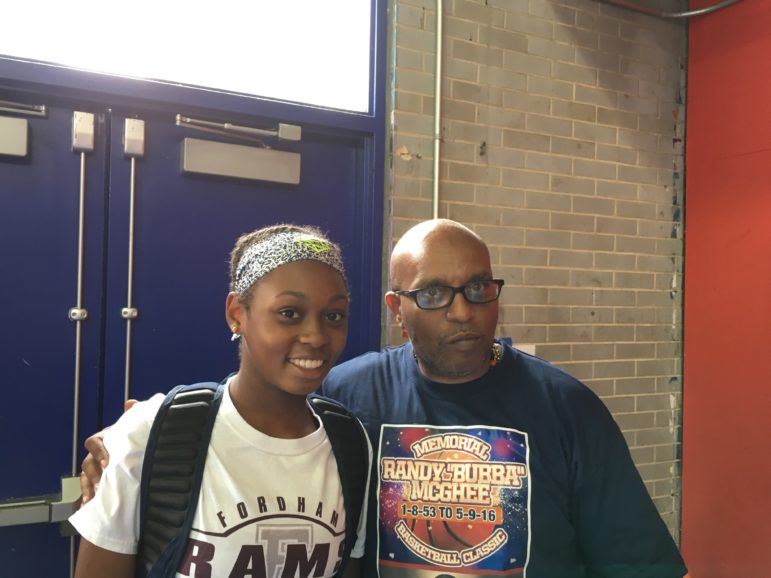

Taylonn Murphy talks to a player participating in the 2nd Annual Randy Bubba McGhee Basketball Classic Tournament in Harlem.

NEW YORK — Steve Ice Waters was a kid when his family moved to Harlem from Los Angeles in 1980. Harlem was beginning to see the early signs of what would become a crack epidemic. It had already witnessed the ravages of the heroin trade and gang violence. The homicide rate in the city that year was a staggering 1,814.

Waters, 13, had no friends or anywhere to hang out. He was aimlessly walking the streets one day when he came across the Police Athletic League (PAL) gym on 123rd Street.

Waters walked into the PAL building and that was when he met the man he would say changed his life. Randy “Bubba” McGhee, called Bub by his many friends, would routinely stay in the facility to make sure the doors would stay open to the Harlem youth whose only alternative was the streets.

Waters walked into the PAL building and that was when he met the man he would say changed his life. Randy “Bubba” McGhee, called Bub by his many friends, would routinely stay in the facility to make sure the doors would stay open to the Harlem youth whose only alternative was the streets.

“He was the first person I saw,” Waters said. “Lucky for me.”

McGhee chatted with Waters for a few minutes and asked him if he would like to become a member so he could avail himself of the programs and the basketball courts at the facility. He said yes, he was eager to join.

“But how much is it?” Waters asked.

“It’s $10,” McGhee replied.

Waters reached into his pockets and pulled the lining out.

“But I don’t have any money,” he said.

“Don’t worry about it,” McGhee said, smiling.

Waters said McGhee gave him some forms for his mother and his life was changed from that point.

“That’s just the way he was,” he said, a look of nostalgia crossing his face. “He was a coach, a mentor, a friend and a father to so many of us.”

In an interview shortly before he died in May, McGhee spoke about what drove him to look out for the youth in Harlem.

“It was my duty to help all the black young men and women in Harlem, to try to teach them to be responsible, accountable young adults,” he said. “It was something that was instilled in me, that we have to be accountable for actions and our behavior, and everyone needs someone to push them and encourage them, so my job was to encourage you guys to do the best you could, to be young men and women. Because, you know, we can have fun, but the bottom line is one day you are going to be grown, you need to be responsible for yourselves. So that was my goal.”

‘Your dad saved my life’

Waters, now 51, recounted this meeting as he stood in the yard of the Dunlevy Milbank center of The Children’s Aid Society in Harlem last week. He was the chief organizer of the 2nd Annual Randy “Bubba” McGhee Basketball Classic, the first tournament for kids and adults since McGhee’s death.

The atmosphere was festive, a cross between a county fair and a family reunion, where more than 200 people were joined by their shared appreciation for one man and a building they consider sacred.

“Look around here,” Waters said. “Ninety percent of the people here came through that PAL gym. They’re here to pay homage to Mr. McGhee.”

Taylonn Murphy talks to another young basketball player at the tournament.

Grown men giggled like children and posed for photographs. They hugged and reminisced like attendees at a high school reunion, except they were celebrating survival on the streets. Most knew someone growing up who is either dead or in prison.

McGhee was a father figure for the youth of Harlem in the ‘80s and ‘90s. That love was printed on shirts and large vinyl banners, and it was on lips of everyone attending the tournament. Nearly everyone wore shirts with his likeness or that paid tribute to him. The printed words echoed what everyone was saying about McGhee: “Father, Brother, Coach, Friend, Mentor, And Hero to the Harlem Community.”

That sentiment was shared by the team manager for NYPD Finest Basketball, the New York Police Department’s goodwill team. When Sgt. Quathisha Epps, the team manager, heard that the tournament was in honor of McGhee she didn’t even need to consult with that team before agreeing to participate.

“Bubba McGhee was a staple in this neighborhood, a fixture; how could we not say yes,” she said. “He kept those doors open. He gave those kids a safe place to go, he built a bridge from the street. That is very much what we’d like to be a part of,” she said, talking about the team’s role as ambassador to the hardscrabble streets.

Epps said she knows there are problems, both real and perceived, between the police and communities like Harlem. But as someone who comes from those streets, she is confident they can be solved, she said.

“This is how you fix it,” she said waving her arm at the mix of children and teens and adults laughing and eating. “You have events like this. There has to be more outlets for the youth, you have to have more resources for the kids.”

[Related: Kansas Overhauls Juvenile Justice System, Emphasizes Community-Based Reinvestment]

She has no patience for people who complain about the trouble youth get into without offering any alternative for them.

“You can’t complain about the streets if you’re not willing to do something to make them better,” she said.

Cristen Corprew, McGhee’s son, said he learned about his father’s influence on several generations of Harlem youth.

“When someone found out that I was his son, they would tell me, ‘Oh, your dad got me my first job,’ or ‘Your dad got me into college,’ or ‘Your dad saved my life,’ said McGhee, 26. “He wanted to make sure that the next generation would do the right thing and would have the opportunity to do something with their lives. A lot of these kids didn’t have a father figure growing up and he wanted to be that for them.”

Waters said he only graduated from Martin Luther King High School thanks to a “whooping” and a long discussion with McGhee. He wasn’t attending class and was on the verge of not getting his degree when his mother reached out to McGhee instead of his own father. It worked, Waters said. He went back to school and graduated on time.

“I was more afraid to disappoint Bub than I was my own father,” he said.

“Every kid needs help at some point,” said Robert Martin, the NYPD team coach and traffic supervisor in Manhattan, who comes from Bedford-Stuyvesant. “We grew up in these streets and we more than anybody understand that. We’re not just out here policing the community, we’re out here trying to reach the youth as well.”

What would Bub do?

The day wasn’t just about remembering the past, it was also figuring out how to meet the challenges posed by the present. In that spirit, Taylonn Murphy was given the Smile for Sonya Randy Bubba McGhee Community Service Award.

Waters introduced Murphy, describing his last tumultuous four years: the two murder trials for the young men who killed his daughter, promising basketball prospect Tayshana “Chicken” Murphy; and the trial of his son Taylonn ”Bam Bam” Murphy Jr. for a retaliatory murder for the slaying of his sister.

“Mr. Murphy, like Randy Bubba McGhee, is a community activist. When ... when we have an unfortunate incident, someone is killed or someone’s child is injured, he is the first one on the scene to try to give some comfort to someone’s family. He has been through it himself. He lost his daughter to violence and, unfortunately, he just lost his son to the prison system. His mission now is to get at these youth and try to keep them on the straight and narrow so they don’t fall into the same traps that his own children did.”

Murphy encouraged the crowd to go out and work with the youth in Harlem, to be a Bubba to a young person on their block, and try to find small ways to keep his work alive.

“One thing I got from Bubba is that he wants his work to continue in many ways,” he said in his acceptance speech. “Not just through me but in each and every individual that’s in here. I think ‘What would Bub do’ when I put feet on the ground to go talk to a young man or try to snatch a young man off the street.”

Murphy said he wants to start by ending the feuds that fuel violence among young people in Harlem. Beyond Harlem, he said, he wants to continue to take his message to besieged communities across the city.

“We’re losing our young people every day to nonsense,” he said.

Not everyone smiled on Murphy. Some people gave him hard looks. His son Bam Bam had been sentenced to 50 years to life the week before for shooting Walter Sumter. Some people made sure they let Murphy know the bad blood persisted. Murphy did not respond in kind. Instead, he sought out people to shake hands or give a hug and offer words of encouragement.

There are certain courts that are special

He had one more trip to a basketball court to make. He traveled 27 blocks north to the corner of 145th Street and Lenox Avenue to the Colonel Charles Young Playground. That’s where young players in the Tri-State Classic basketball tournament were wearing jerseys with an in-game picture of Chicken in her early teens dribbling a ball, a look of fierce concentration on her face.

Taylonn Murphy talks to a player after her game at the Tri State Basketball Tournament in Harlem.

The commissioner of the Tri-State is Antonio “Mousey” Carela, the father of Starr Breedlove, a college player who was a childhood teammate and friend of Murphy’s daughter Chicken.

In sharp contrast to the tournament Murphy just left, police officers manned a makeshift line made out of barriers instead of playing in games with the youth. They rifled through players’ and visitors’ bags. They stared stone-faced at visitors as they entered. Overhead the roar of a police helicopter competed with the announcer as it swooped again and again above the court where young girls played a game.

This court holds a special significance for Murphy.

“I can feel her presence,” he said, pausing on the sideline to watch. “Like she’s here with me.”

Murphy notices one girl getting benched and not responding to her coach’s advice. She is having a bad game and she is too frustrated to listen to any adult counsel. She turns her head away from him while he tries to offer her some advice.

Murphy approaches the girl after the game. He recognized her from his work trying to end the feud that cost his daughter’s life.

“I know you were frustrated but you need to relax, you need to relax,” he says. “No matter how hard it seems you need to keep your head. The game has to be fun. Or else what’s the point?”

At first she looks at him with practiced teenage indifference.

“Trust me, I learned a lot from this game. You know the girl who is on the jersey, Chicken Murphy? That’s my daughter.”

She looks at Murphy again with renewed interest.

“Oh! You’re the one that talked to us in Manhattanville?”

“Yeah, that’s me,” he replied.

Her face transforms from being twisted in frustration and anger to one that is willing to listen.

More related articles:

Proposed Georgia Budget Shifts Money to Community Programs

OP-ED: Community Engagement as a Key to Juvenile Justice Reform

Report: Evidence Shows Community-based Programs Work Better than Incarceration