I graduated from high school in June 1975. On June 30 of that year there were 52,190 youth in public or private juvenile facilities charged with or adjudicated for a delinquency or status offense. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) wasn’t yet a year old. The National Center for Juvenile Justice, which I now direct, was not yet 2 years old.

Since that time there have been many changes in the juvenile justice landscape. The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974 (JJDPA) was just beginning to have an impact on the way states handled youth who violated the law — reducing the use of secure confinement of youth whose behavior would not constitute a crime for an adult and insisting on “sight and sound” separation if youth were confined with adult inmates.

JJDPA later required that states not confine juveniles in adult jails or lockups except in limited circumstances. Over the decades, there were wars on drugs, omnibus crime control measures and several due process-focused Supreme Court decisions. Those rulings continued on the heels of Kent (1966) and Gault (1967) to make clear that “justice for all” included children too.

Starting in the mid-1980s, the rates at which youth entered the juvenile justice system, especially with charges of violence, rose sharply. Predictions of a coming wave of “superpredators” was used to justify responding more harshly to youth law-violating behavior.

Thus, not only were the numbers of youth entering the juvenile justice system increasing to levels never seen before in U.S. history, so too were the numbers of youth placed out of their homes because of their law-violating behavior. The number of youth in public and private juvenile residential placement facilities reached a peak of 108,802 in 2000. In the 25 years from 1975 to 2000, the number of youth in residential placement more than doubled.

For me, the mid-1980s through at least 2000 felt like a very dark time for juvenile justice and the youth involved in the system.

Somewhere along the way, things began to change. Instead of the numbers continuing to rise, they began to turn around. Reform initiatives like the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative and Models for Change: Juvenile Justice Reform Initiative engaged advocates and juvenile justice system professionals alike. A growing body of research spelled out what worked and what didn’t in terms of juvenile justice programs and policies. And research on adolescent brain development helped us all understand how and why kids are different from adults and why that matters to juvenile justice system responses to their behavior.

In the midst of all this, the country experienced the Great Recession, which put tremendous budget pressures on states, including their juvenile justice agencies. In 2013, the National Academy of Sciences released “Reforming Juvenile Justice: A Developmental Approach” with concrete recommendations for changes that would improve outcomes for youth involved with the juvenile justice system.

Now, many of the things we count to gauge how the juvenile justice system is doing seem to be heading in the right direction. With fewer youth in the system, there is some hope that we can do a better job with them. We may not be fully out of the darkness, but there is light.

Today, I’m more than four decades past my high school graduation and although that means I’m “way old,” as my kids keep reminding me, I’m feeling optimistic. Why, you ask.

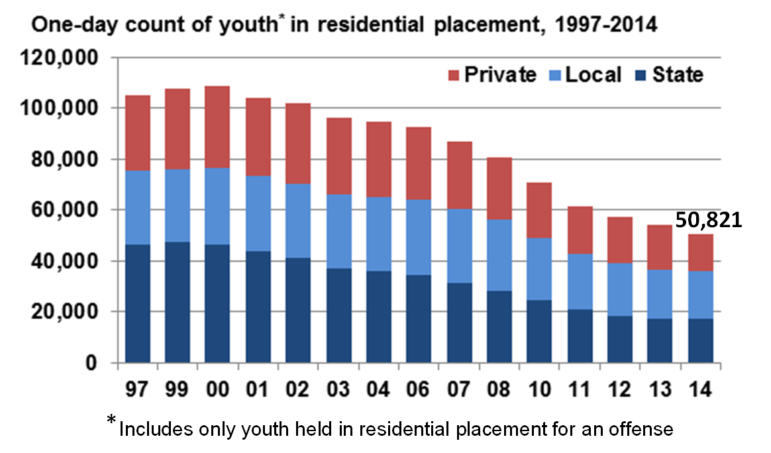

Because analysis of the most current data collected through OJJDP’s Juvenile Residential Facility Census shows the number of youth held in juvenile residential placement facilities reached a new low point in 2014 — 50,821. That means that the 25 years of continuous growth in the residential placement population has been erased in 14 years. The one-day count of youth in residential placement in 2014 is 53 percent below the figure for 2000 (and 3 percent below that 1975 figure).

The number of youth held in state-operated facilities showed the largest relative decline during the 2000–14 period, falling 63 percent, compared with a 54 percent decline in the number of youth held in privately operated facilities, and a 37 percent decline for those held in locally operated facilities.

As a result of these declines, more youth were held in locally operated facilities in 2014 than in state- or privately operated facilities. The shift away from state-operated facilities has reduced the state share of youth in residential placement from 44 percent in 1997 and 1999 to less than 35 percent every year since 2011. Reformers of all stripes can take comfort in knowing that they have had an impact.

I know not to be overly joyful, though. There is light, but shadows remain. Juvenile justice systems around the country still have a lot of room for improvement. In just about every jurisdiction, there are a disproportionate number of youth of color in the system.

We need to figure out how we can ensure that ALL youth benefit from reforms, not just a privileged few. In too many places, the juvenile justice system treats youth shamefully. In many parts of the country, communities do not trust the justice system to treat their youth fairly. That is something we ignore at our own peril.

As a researcher I believe that data and research are important, even key, to juvenile justice reform. Too many juvenile justice agencies, service providers, counties and states do not currently have the data and analysis capacity they need to know if their responses to youth law-violating behavior are working.

That is also something that can’t be ignored. I am encouraged by the growing number of places that are using data for illumination, which can only be sustained with an investment in data collection and analysis infrastructure.

To learn about youth placement facilities, look for the data snapshot on the 2014 Juvenile Residential Facility Census and the forthcoming bulletin “Juvenile Residential Facility Census 2014: Selected Findings” on the OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book website or NCJJ’s website.

Melissa Sickmund, Ph.D., is the director of the National Center for Juvenile Justice, which is the research division of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Points of view expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of OJJDP or the U.S. Department of Justice.