NEW YORK — If 20 murdered children in a small-town school could not change the debate, what would?

John Richie

This is the question that haunted filmmaker John Richie. Richie was still screening his first movie “Shell Shocked,” a documentary about gun violence and youth in America’s murder capital, New Orleans, when 20-year-old Adam Lanza blasted his way into Sandy Hook Elementary with a semi-automatic rifle and killed a classroom of first graders.

Richie had spent years immersed in the world of guns in New Orleans, where, as one teenager he interviewed told him, it was easier to get a gun than a textbook.

Now, he watched as the intractable and implacable gun debate took shape and calcified into predictable camps. But he saw one poll number that obsessed him. It was that 91 percent of people had said they agreed with closing what is popularly known as the gun-show loophole. It allows people who are not licensed gun dealers to sell guns without a background check of their customers. Richie was perplexed at how so many Americans could support comprehensive background checks and how little it meant to leaders in Washington who refused to act.

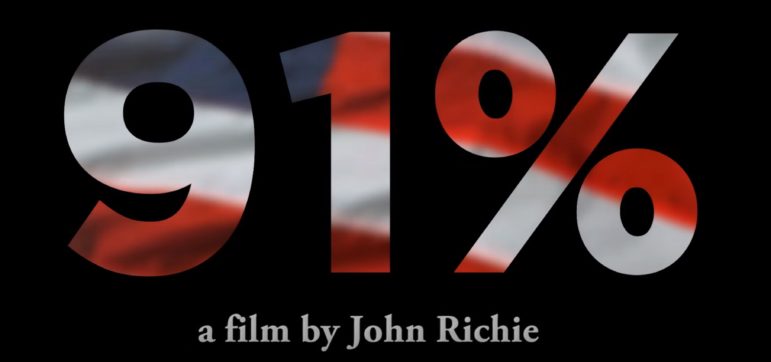

That number, that 91 percent, inspired Richie to make a sequel. Today Richie is set to release “91%: A Film About Guns In America,” the sequel to “Shell Shocked.” The film focuses on the majority of Americans who support comprehensive background checks — a factor that Richie says could have prevented thousands of gun violence tragedies around the country in recent years.

That number, that 91 percent, inspired Richie to make a sequel. Today Richie is set to release “91%: A Film About Guns In America,” the sequel to “Shell Shocked.” The film focuses on the majority of Americans who support comprehensive background checks — a factor that Richie says could have prevented thousands of gun violence tragedies around the country in recent years.

Richie, a child of the deep South who lives in New Orleans, said he is an advocate for reining the debate into what he calls the “sensible middle.” After some screenings, he said, he has been impressed by people on the other side of the issue who have said they were moved by the film and felt that it was nonpartisan.

“It’s a baby step, but I’ll take it,” he said.

After spending three years in the trenches of the fight over guns and gun regulation, he says he is finally seeing what even the lifeless corpses of Sandy Hook could not change.

“We can see it in this election,” Richie said. “It’s become such a big part of this presidential election. Hillary [Clinton] has made reforming this loophole a part of her platform. I think it’s just a matter of time before we see movement on something that until today we haven’t seen movement on since 1994. We are putting into office people who support background checks and stronger regulations to get guns out of the hands of people who shouldn’t have them.”

For almost a decade now Richie has gone to sleep and woken up immersed in the world of gun violence. In 2007 he started making his first documentary, “Shell Shocked,” a cinema-verite look at how gun violence affects young people in New Orleans. Nearly a decade later he has finished a second. This accomplishment did not come without a psychic toll.

“There’s been some dark moments and dark times but it’s given me a deeper appreciation of life. I am looking forward to working on something other than guns, guns, guns and gun politics. I would never, ever say I regretted it though,” he said. “At the same time it can be really inspiring, it can really make you appreciate life and the people who you care about around you. ”

As part of his reporting for the movie, Richie met victims of gun violence who are still dealing with the consequences of the shootings years after the shots were fired. There is Carolyn Tuft, who watched her daughter get gunned down and killed in a mall in Salt Lake City while going shopping for Valentine’s Day cards. There’s Judi Richardson, whose 25-year-old daughter Darien was shot to death by masked intruders who burst into her bedroom in Portland, Maine, while she slept. A young man was killed by the same gun a month after Darien’s murder, police said.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Richie said. “You go to their houses and see the narratives of their lives in pictures — special events, graduations, vacations — and their child is ripped out of there. There’s a certain amount of suffering every day of their lives that easily could have been prevented if there had been stronger gun laws.”

There isn’t a particular person that moved him, but he was left inspired by them all, he said.

“It would be hard to pick just one person who we featured in the film or that we talked to while making the film who wasn’t a constant reminder that this is not about politics,” Richie said. “This isn’t about policy. The end result … is literal life and death. This is the difference between a safe, comfortable society, or one in which you have to live in fear of being shot down randomly. This is what it’s about.”

He said he was constantly humbled upon meeting people who tried to turn tragedy into reform.

“One of the most inspiring things about the people featured in the film is that they took this awful tragedy and tried to turn into something meaningful,” Richie said. “They’re out there trying to prevent what happened to them from happening to the rest of us.”

There were numerous moments when Richie wondered if he would have the emotional endurance to respond to the horror of sudden, deadly violence the way his subjects in the film did.

“I think there’s a lot of people, you and myself, who deal with this tragedy all the time, and I can only imagine what that loss would feel like and the amount of grief that comes with it — it would be absolutely crippling. I would hope I could muster up enough strength to do what they have done.”

He hopes the movie will jar viewers into an understanding of how there is a universe of tragedy that continues after the mainstream media moves from one high-profile shooting to the next, he said.

“If you are not immediately touched by gun violence or actually shot, then you don’t realize what the long-term effects are on real people’s lives,” Richie said. “We hear these stories in the news and the narrative is always the same: The person was shot and they either lived or they died. For you watching at home that’s the end of the story. We don’t think about what happens afterward.”

A crucial, underreported part of the story, he said, is to understand how far-reaching gun violence is and how long-lasting its damage can be.

“We spend well over a billion dollars a year treating gunshot victims — to treat this wound that never really heals,” Richie said. “There’s tons of scar tissue and fragments of bullets inside people. I’ll tell you one thing, though; these people, despite all they’ve been through, have moved to activism. What would break a lot of people, they try to turn into something good. The people we show in the film use this unbelievably horrific event in their life to prevent it from happening to other people.”

Richie spoke to dozens of people for the film, mixing interviews with experts and real-life stories of victims of gun violence with verite footage of them at National Rifle Association conventions, coping with day-to-day struggles and being activists in Washington, District of Columbia. “91%” focuses on only a handful of stories.

“Some people lost their lives, some people lost the life of a child,” he said. “Some are luckier than others. Some were just shot.”