DURHAM, N.C. — David Johnson was 16 years old when he faced his first criminal charge in a North Carolina court that considered him an adult.

He remembers being overwhelmed by the proceedings, uncertain of what it would mean to take a plea or to spend years in prison — and to end up with a permanent criminal record. After all, he says, he was just a kid.

“I didn’t realize the consequences that it could have for me down the line,” he said.

Today, Johnson is an outreach worker with Bull City United in Durham, where he focuses on discouraging violence in the neighborhoods where he grew up. He tells teenagers about how he picked up his first adult charge for a stolen car, then at 17 was charged with assault with a deadly weapon and served nearly 10 years in prison.

Johnson says he talks to the teenagers he works with all the time about what could happen if they come in contact with the criminal justice system. He wants them to know that in North Carolina, 16- and 17-year-olds are charged as adults, not juveniles, a reality he says makes it harder for young people to get access to the programs they need to get on a healthy path.

“You’re killing my life before I even get a chance to live it,” he said.

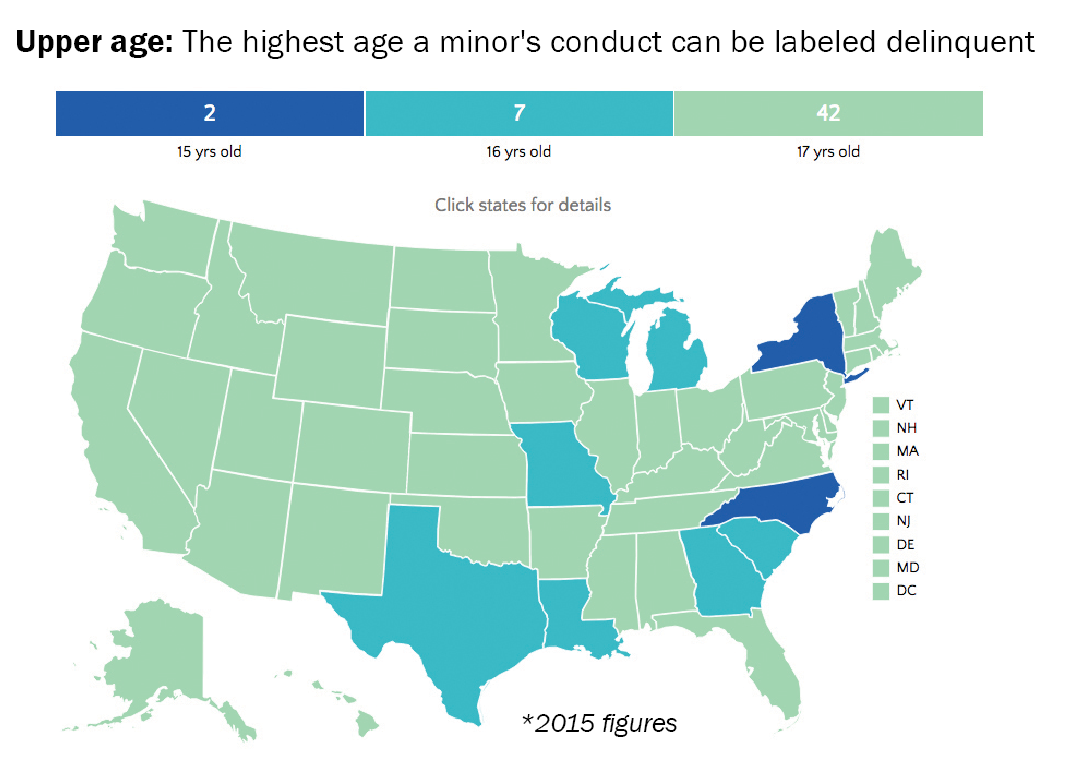

North Carolina and New York are the only two states where 16-year-olds are routinely charged as adults for any offense, from petty misdemeanors to violent felonies. And only a handful of states do the same for 17-year-olds.

Across the country, keeping teenagers in the juvenile system until their 18th birthday has become the norm, with ways for prosecutors to send teenagers into the adult system if they think the crime requires it.

.

In 2016, South Carolina lawmakers swiftly and unanimously passed legislation to keep teenage offenders in the juvenile system until age 18, rather than automatically sending them to adult court. Louisiana lawmakers did the same with only a handful of dissenting votes. Since 2009, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts and New Hampshire also have “raised the age.”

North Carolina lawmakers have debated for years whether they also should make the change. Now, supporters of raising the age in the state say 2017 could be their year, as traditional opponents such as police and prosecutors have shown greater support than ever before, and a state commission on judicial policy led by Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Martin has endorsed the change.

“It just feels like a changing tide,” said Susanna Birdsong, policy counsel at the ACLU of North Carolina.

Supporters argue that 16- and 17-year-olds belong in the juvenile system because they still are maturing — and are therefore less culpable and more primed for rehabilitation than older offenders.

In addition, they say adolescents charged as adults must deal with criminal records that limit their educational and employment opportunities — and put them at a disadvantage compared with their peers in other states. Plus, the small number of teenagers charged with serious crimes who spend time in adult facilities are particularly vulnerable to physical and sexual assault.

Rodney Robbins knows well the way a criminal record can follow a family for years.

Twenty-one years ago, his 16-year-old son was part of a group of teenagers charged in a car-vandalizing spree. His son, who also has developmental disabilities, has struggled to find work, even losing a job when a post-hiring background check turned up his misdemeanors.

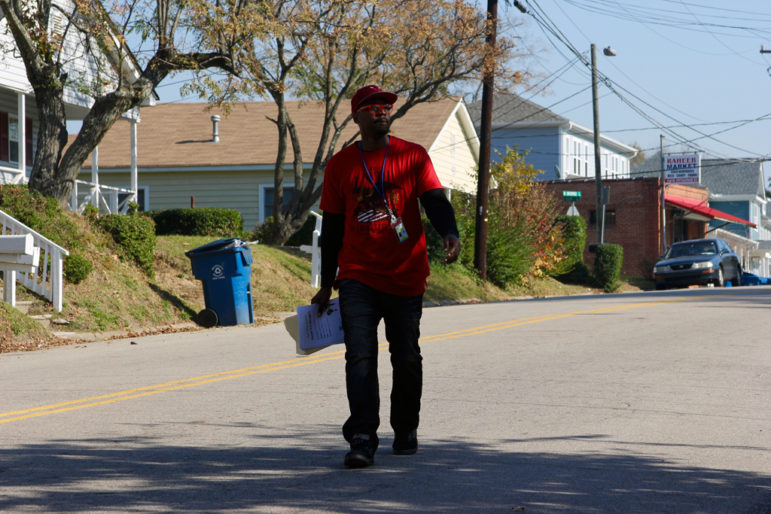

Convellus Parker, 34, right, an outreach worker with Bull City United, canvasses a Durham neighborhood in support of the group's anti-violence initiatives. Parker, a former offender who was charged as an adult at 17, supports raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction in North Carolina.

The family had mistakenly thought he didn’t need to disclose his record because of his age at the time of the offense since juvenile records typically are sealed.

And, there are the what-ifs. Robbins often thinks about what he could have done differently after his son was charged. Should he have hired a private attorney, rather than relying on a public defender? Should he have mentioned his son’s developmental disabilities to the court?

“We continue to live this every day. It’s tiring, it’s relentless,” he said.

Robbins testified last year, one of dozens of children’s advocates and parents who did so at public hearings across the state, one sign of the growing momentum to change the state’s policy.

Legislative action possible

In the past, raising the age in North Carolina has had support from organizations across the political spectrum, from the conservative John Locke Foundation to the liberal American Civil Liberties Union. But legislation always stalled, often as detractors cited concerns about costs as well as public safety.

This year though, traditional opponents of the measure, including law enforcement and prosecutors, also have given qualified support to raising the age. And, the North Carolina Commission on the Administration of Law and Justice, headed by Martin, was expected to release a report in February (not available at press time) that includes a committee’s recommendation to raise the age.

At the group’s final meeting, Martin said he plans to work with the legislature and governor to pass such a measure.

“Let’s get to work and get it done in the long session,” he said.

State Rep. Duane Hall, a Democrat, said in early February that he expected to introduce bipartisan legislation that largely tracks with the commission’s recommendations during the upcoming session.

Hall, who has co-sponsored raise the age legislation in the past that cleared the House, said costs have typically been the biggest stumbling block in recruiting lawmakers to support raising the age. While the change would have significant start-up costs, other states have saved money in the long term because of decreases in recidivism and reduced facility costs.

“Once you get it going, it’s cheaper to have 16- and 17-year-olds in the juvenile system. People are just fearful of the upfront costs,” he said.

But Hall said costs shouldn’t be the only consideration. Teenagers’ capacity for change and their safety also should drive the decision to raise the age.

“It’s the right thing to do,” he said.

Despite the greater consensus around raising the age, supporters warn it’s hardly a done deal. They expect some lawmakers will have objections about costs, as well as public safety.

David Johnson, an outreach worker with Bull City United, canvasses a neighborhood in support of anti-violence initiatives. Johnson was charged with assault as an adult in 1998 when he was 17-years-old. He supports raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction so that 16- and 17-year olds in North Carolina don't automatically land in adult court.

For example, in a letter to the North Carolina Courts Commission, which also has endorsed raising the age, recently retired state Rep. Paul Stam, a powerful Republican, said he has concerns that young offenders’ crimes would be shielded from the public because they would have juvenile, rather than adult, records.

“To take that away is a real mistake. There are multiple felony offenses that the public, future spouses and employers may never hear,” he wrote.

Stam also said he has concerns the change could encourage gangs to use 16- and 17-year-olds for certain crimes, knowing they likely won’t be tried in adult court and will face lighter penalties.

No violent felonies

One of the notable characteristics in the committee’s recommendation is what it excludes. As is the law in some states, the group set apart some serious, violent felonies, meaning 16- and 17-year-olds charged with crimes such as murder or rape would still be considered adults after a finding of probable cause or indictment.

Prosecutors also would retain the ability to petition a judge to send other teenagers to adult court if they think it necessary.

Few of the young offenders in North Carolina are convicted of violent offenses. In 2014, only 3.3 percent of the 5,689 16- and 17-year-olds convicted were charged with the violent crimes that the group recommended excluding. Another 80.4 percent were convicted of misdemeanors and 16.3 percent of nonviolent felonies.

Bob Simmons, executive director of the Council for Children’s Rights in Charlotte, said he ultimately would like to see all adolescents under 18 remain in juvenile court, but the recommendation is a strong step in the right direction.

“We, as advocates for children and as juvenile defenders, believe children should be treated as children regardless of the severity of the offense because the brain science about their ability to control their impulses doesn’t differ based on that severity,” he said.

The recommendation also stresses the importance of information sharing among state agencies and full funding to implement the changes, a point that was critical to gaining the support of the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association.

“Previous legislation that has been vigorously opposed by the Association merely deleted the number 16 and replaced it with the number 18,” the association wrote in a letter to the commission indicating their support. But the committee’s recommendation takes into account “practical real world concerns” identified by the sheriffs, they said.

The North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys also wants to see the Legislature put adequate training and funding in any bill before they can support it, said Peg Dorer, director of the group.

Prosecutors also have said they want more authority to decide which juveniles get sent to adult court without having to go in front of a judge. But Dorer said the main priority for the group is adequate funding.

“There’s a lot of interest, and I do think it stands as good a chance as it ever has if the General Assembly is willing to put the resources to it,” she said.