Proposed legislation would move juvenile justice in California closer to rehabilitating youth rather than punishing them, juvenile advocates say.

State sens. Holly Mitchell and Ricardo Lara, both Democrats, introduced bills in March that would keep more youth out of the juvenile justice system by focusing on crime prevention and family ties rather than incarceration.

While none of the proposed laws are groundbreaking, they could lead to changes in other states.

“Some states may look at look at California and say if California can do it with all those kids, wow, then maybe we can do it, too,” said Melissa Sickmund, director of the National Center for Juvenile Justice.

The four bills are:

- SB 190, which would eliminate court and administrative fees that families of juvenile offenders pay.

- SB 394, which writes into state law a U.S. Supreme Court decision that minors can’t be sentenced to life without parole.

- SB 395, which would require that minors talk with a lawyer before waiving any legal rights.

- SB 439, which would keep children 11 and under out of the juvenile courts.

“I feel optimistic that our entire juvenile justice and equity package will be signed into law," Mitchell said. "My colleagues in the Legislature and the governor’s office have heard the general public loud and clear in their approval of Proposition 47. The people have demonstrated their desire for a shift away from a punitive orientation system, to a new approach that focuses on prevention, and rehabilitation."

SB 439 has been approved by the Senate; the other three bills are awaiting that step.

Next Friday, June 2, is the deadline for bills to be passed out of the legislative body where they were introduced.

If approved by the Senate, similar bills must be approved by the state Assembly. The bills would then go to the governor for approval, which is not expected to happen until the fall.

The Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ) in San Francisco co-sponsored SB 190 and SB 439 to help combat the long-term trauma that the financial burden of fees and the juvenile court system have on youth and their families.

Families of incarcerated youth are charged administrative fees that can easily reach thousands of dollars and disproportionately affect poor and low-income families, said Maureen Washburn, a policy analyst at the CJCJ. A family in Orange County, for example, accumulated $16,000 in debt and ended up losing their home to pay the bill, she said.

The fees vary by county. Some, including Los Angeles County, have already suspended charging those fees.

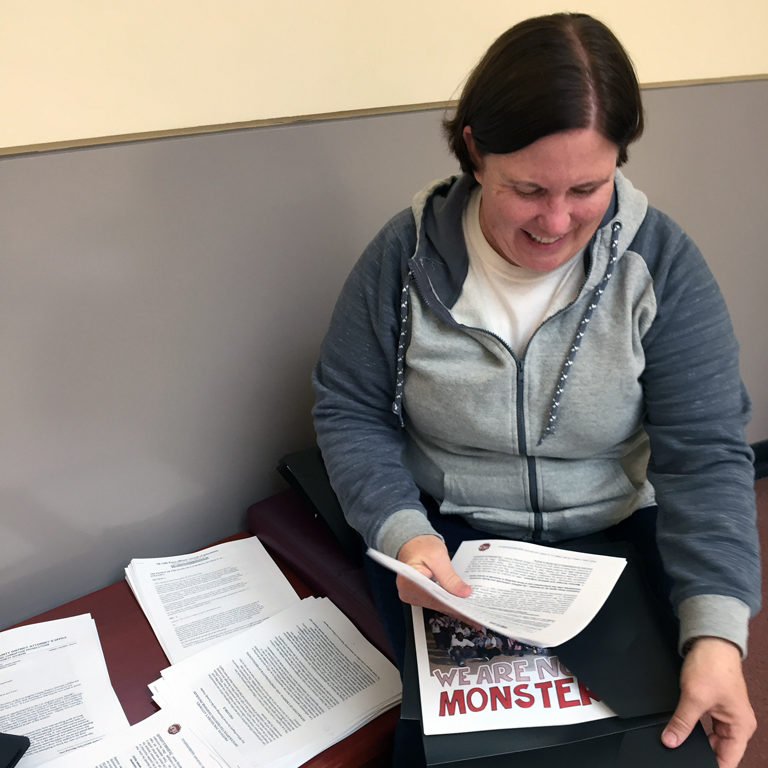

Michael Wilson, whose family had to pay for his detention when he was incarcerated as a teen, was in Sacramento this week working with the Youth Justice Coalition to pass the bill.

Youth Justice Coalition member Michael Wilson.

“For me personally, the reason why it’s very important is because number one, it doesn’t bring any type of stability to the home once that young person is released,” Wilson said. “It actually causes more harm, and it’s been shown that this bill and these charges directly affect black and brown underserved and underprivileged families.”

Laura S. Abrams, a professor at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs who specializes in the study of juvenile justice, said charging families for incarcerating their children makes no sense.

“We provide county services for other types of facilities for young people at no charge,” she said. “I never quite understood the philosophy of charging families for an involuntary confinement. To charge a person is just adding salt to the wound.”

“We know that the majority of the families that have young people enter the juvenile justice system are poor or low income. Charging these families only exacerbates the problems,” said Patricia Soung, senior staff attorney and policy associate for the Children’s Defense Fund in Los Angeles.

Keeping children under 12 years old out of the juvenile justice system is also a priority for the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

For more information about EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES, go to JJIE Resource Hub | EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES

California currently does not have a minimum age threshold for prosecuting children. Having one would follow guidelines established by the United Nations. Nineteen other states already have minimum age thresholds.

Opponents to the age threshold expressed concern that children who commit serious crimes, such as murder, could endanger communities. Advocates say very few youth under 12 commit serious crimes, and those who do commit such crimes usually have serious psychological problems that incarceration would not solve. In 2015, no serious crimes were committed by children under 12 in California, according to the CJCJ.

Washburn said children under 12 who commit crimes may have psychological issues or problems at home that are better resolved through counseling or placement outside the home rather than incarceration.

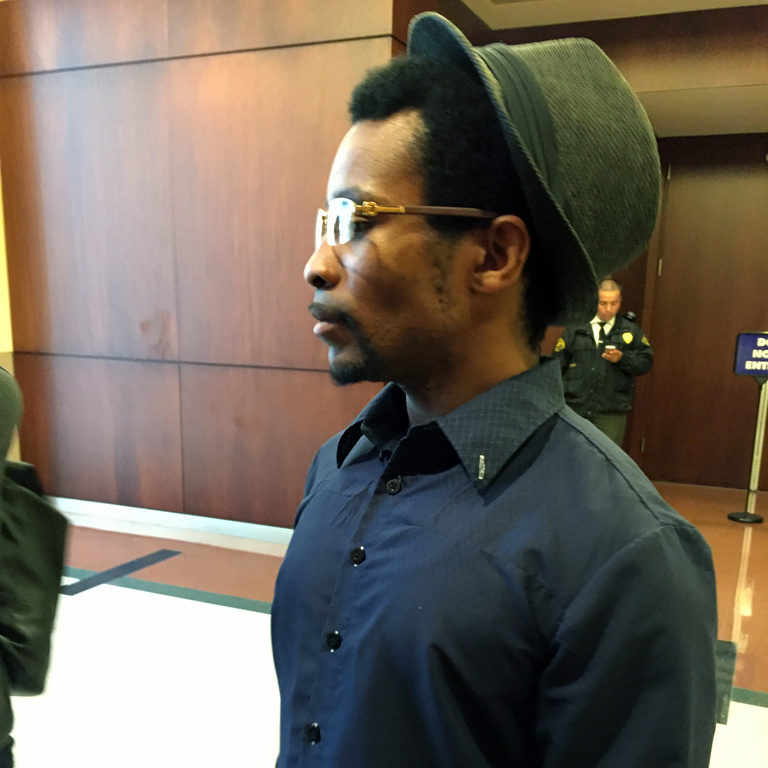

Tauheedah Shakur (left) and Kim McGill of the Youth Justice Coalition in 2016.

“We are just coming into compliance with what is happening elsewhere,” she said. “A lot of children are being swept into the juvenile justice system at an early age.”

“Incarceration is really inappropriate for very young children,” said Maria F. Ramiu, senior staff attorney for the Youth Law Center in San Francisco. “They should be able to deal with these issues with social service agencies.”

“We are over-responding by incarcerating children,” Soung said, noting that in 2015 a 5-year-old was arrested for violating curfew. “Existing alternatives should be able to address the issues.”

Banning minors from being sentenced to life without parole and requiring consultation with a lawyer before they waive any legal rights is needed because minors are not yet developed enough mentally to understand their actions, according to advocates.

“Young people are different, we can’t treat them like adults,” Soung said. “A life sentence without parole is an extreme punishment. We cannot know at that young of an age what kind of person they will become.”

“Kids are more capable of change,” Ramiu said. “They should have the opportunity to get out of prison.”

The waiving of so-called Miranda rights — the right for a person to remain silent and to have an attorney present during questioning by police — is sometimes difficult for youth to fully understand, advocates say.

“In the face of a police officer, young people can be intimidated into talking,” said Abrams of UCLA. “It would have a major impact on young people if they had an attorney present during questioning.”

Wilson remembers that feeling of intimidation.

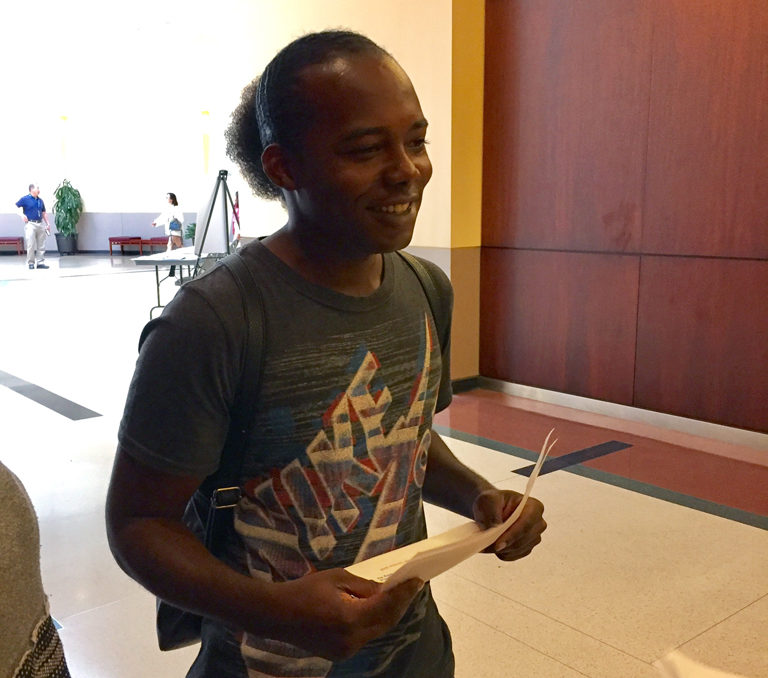

Youth Justice Coalition member Dayvon Williams.

“Being a young person, you don’t understand the gravity of the coercion that they use. They kept directly giving me a story and asking me, ‘Isn’t this right? Isn’t this right?’ That coercion is very devastating,” he said. “I use my experience to help those young people who may have not committed a crime but are so scared.”

Wilson was among 10 YJC members who traveled to Sacramento to visit with legislators and lobby for the four bills and several more.

“I’ve been organizing since I was 13,” says 19-year-old Tauheedah Shakur, who also went to Sacramento. “We do things on issues that probably will never affect us, but ... will affect our community. Our community is us.”

One of the bills YJC was supporting would have made records of police misconduct available for public review. While the bill died early, YJC members are working locally to advocate for changes in the complaint process to improve how incarcerated youth are treated. They followed up their Sacramento trip with a presentation before the Los Angeles County Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission, where they presented their recommendations.

To YJC member Dayvon Williams, making sure youth are aware of the complaint process and that it is clearly posted in facilities is very important. “We’re going in here to testify about that,” he said.

At 18, he spent seven months in jail and was placed in solitary confinement for two weeks because the guards thought he was faking a seizure.

“The complaint process is different depending on where you are,” explained Kim McGill, YJC organizer. “There’s not really any clear standards. You might ask a deputy and he might say, ‘Well you can just give me the complaint,’ or you’ll ask a deputy and he’ll say, ‘We don’t have any complaint forms,’ or you’ll ask a deputy and it’s like ‘I don’t know where the complaint forms are.’”

This story has been updated.