In 1993, Louis Gibson was arrested at age 17. He was sentenced to life without any chance of parole.

Today, Gibson, 41, is a model inmate, one of a select few living at the Louisiana State Police Inmate Barracks in Baton Rouge, where he does maintenance on state police aircraft.

Until recently, it seemed he would die in prison. He was convicted of killing another teen, a friend he’d grown up with.

But two bills passed through the Louisiana Senate and the House could give Gibson and about 300 other juvenile lifers a chance at parole.

First, legislators must resolve key differences between the House and Senate versions of Senate Bill 16, sponsored by Republican state Sen. Dan Claitor of Baton Rouge. The Senate version promises parole eligibility for juvenile lifers after 25 years; the House version offers it after 30 years.

The Senate version also bars all future juvenile life-without-parole sentences, while the House version eliminates future sentences for almost all of them, by barring the sentence for second-degree murder defendants, who made up 92 percent of recent defendants.

Both the parole eligibility and tightened future sentencing were recommended by a task force convened by Gov. John Bel Edwards in an effort to fight crime in smarter, more cost-effective ways.

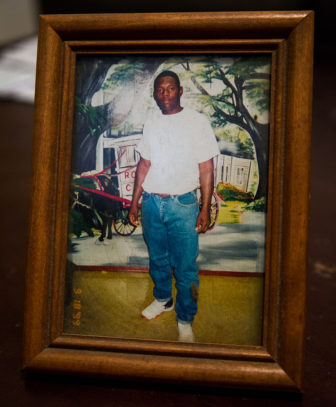

Family photo

Latrone Davis, a friend of Louis Gibson, was fatally shot at 19.

If enacted, the law will “mark a substantial win for Louisiana and for the country,” said Jody Kent Lavy, executive director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a national advocacy group.

For the state’s 300 or so juvenile lifers, the true test of the bill will be whether it allows for more than a few dozen of them to be released. Still, the legislation could be a big step for Louisiana, which has flown in the face of a few different U.S. Supreme Court rulings about juvenile lifers.

At night, in his prison bed, Gibson replays in his mind what happened that night 24 years ago. He wishes he’d never driven with an older pal to a New Orleans hip-hop hotspot called the End Zone. They arrived around midnight. By 1:30 a.m., his friend Latrone Davis, 19, was dead.

It seems like an all-too-common story of young New Orleans men turning to guns over small disagreements. But years later, the insights of those involved help to illuminate Senate Bill 16 by examining not only senseless violence, but also poverty, punishment and forgiveness.

The legislation that became Senate Bill 16 was first broached in Capitol hallways in 2012, after the Supreme Court ruled that laws requiring life-without-parole sentences for juveniles violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Though Louisiana soon eliminated mandatory life-without-parole sentencing for juveniles, it allowed the sentences after a hearing to consider mitigating factors related to the defendant’s young age and upbringing.

Statewide, 75 percent of the juveniles who have had those hearings since 2012 have ended up going to prison for life. So the sentence still looks automatic, said Professor Katherine Mattes, who directs the Criminal Law Clinic at Tulane University Law School.

That runs contrary to the Supreme Court’s declarations that these sentences should become “rare” and “uncommon,” Mattes said. “Seventy-five percent is not uncommon. Seventy-five percent is not rare,” she said. “We’re putting ourselves in the crosshairs of the Supreme Court again.”

Family photo

As a child, to put food on his table, Louis Gibson worked odd jobs, carrying grocery bags to cars in Central City, then tap-dancing and shining shoes in the French Quarter. By fifth grade, when assigned an essay about whom he looked up to, he couldn't write the truth: that he admired the neighborhood drug dealer.

Two years ago, researchers with Phillips Black, a public-interest law firm in St. Louis, found that Louisiana was one of five states responsible for the “vast majority” of juveniles in the U.S. serving life sentences. Because of that history, the effect of the Louisiana legislation will ripple far beyond Baton Rouge, Kent Lavy said.

Juvenile lifers like Gibson have been waiting for Louisiana to act for more than a year, since the Supreme Court ruled in Montgomery v. Louisiana that states must offer them “meaningful opportunity” for release.

Henry Montgomery, the plaintiff in that case, has been a prisoner at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola since 1970. Claitor was a toddler when Montgomery was convicted mere miles from his district, he told a Senate committee. To him, the directive in Montgomery’s case seemed both clear and personal. “This is a mandate from the Supreme Court saying, ‘Fix it,’” Claitor told his colleagues.

If the bill becomes law, no one will be automatically released. Juvenile lifers can earn a parole hearing if they meet certain behavioral and educational criteria and have served the required time, whether 25 or 30 years.

The bill’s behavioral and educational requirements may present a hurdle for many. According to a preliminary estimate by the state Department of Public Safety and Corrections, 72 inmates have served enough time, but fewer than 1 in 5 of them met the other requirements to get a hearing.

Bill follows adolescent brain development research

Claitor’s bill prompted hours of charged testimony in the House and Senate committees that oversee criminal justice. Tearful family members testified about teenagers who had brutally murdered grandmothers, young children and parents. A sheriff’s deputy described his shock at a particularly grisly crime perpetrated by a teen.

“It’s difficult. Lives are torn apart; people are dead,” Claitor said somberly in a committee meeting after he’d heard the testimony.

Dr. Kiana Andrew, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Tulane University School of Medicine, explained to the Senate committee that, until the brain is fully formed at about age 24, young adults are like cars that cannot stop.

“The brakes aren’t even there yet,” Andrew testified. “They’re more impulsive, are more likely to be involved in risky, dangerous behavior. They really do not think before acting.”

This relatively new body of science is central to the recent series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions re-examining juvenile sentencing. In 2012, Justice Elena Kagan quoted a 2005 decision as she emphasized “the great difficulty … of distinguishing at this early age between ‘the juvenile offender whose crime reflects unfortunate and yet transient immaturity, and the rare juvenile offender whose crime reflects irreparable corruption.’”

“How can anyone see into a crystal ball and know what a child will be like in 20 or 30 years?” asked Aaron Clark-Rizzio, who heads up the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, which includes a better-known legal arm, the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana. “Even those who have caused harm have a tremendous ability to mature and change, something we see every day as juvenile public defenders.”

A childhood of poverty, hunger and abuse

Dozens of certificates and honors earned in prison point to Gibson having changed since he pulled the trigger that night. And he feels deep remorse. “Latrone and I were friends,” he said. “We were not enemies. We were just following street protocol that night.”

Since he was a boy, Gibson had to hustle for his dinner. At first, he carried bags for customers leaving the Venus Gardens Grocery in Central City, one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Then he’d buy some sandwich meat and bread and bring it home for him, his little brother and their two sisters.

“Whatever I got at the store, that’s what we ate,” he recalled recently. Neighbors from that time remember feeding them and seeing little Louis using safety pins to hold tattered shoes together.

“We went through a lot, as far as my mom being on drugs and on the streets,” said Cha-Chi Gibson, 40, his younger sister. “Louis actually took the role of being our daddy.”

The Advocate

Cha-Chi Gibson, the close sister of juvenile lifer Louis Gibson, poses for a photo in front of her home in New Orleans, Wednesday, May 31, 2017. At the age of 17, Louis Gibson was arrested. He was sentenced to life without parole after he shot someone he grew up with. Gibson is now 41 and the state legislature is looking at a possible 300 other juvenile lifers including Gibson to receive a chance at parole. She is a security guard.

Their older sister Zabrine Gibson Priestley, now 42 and a minister living in Texas, was molested at a young age and gave birth at 13. “I think that it’s only by the grace of God that we survived,” Priestley said.

Cha-Chi Gibson, a security guard, has worked in private-security and sheriff’s offices for the past 16 years. “I’m on the other side of the law,” she said, explaining how she watched her brother negotiate high-poverty, high-crime neighborhoods in Central City and where the Orleans Parish criminal courthouse stands.

The Advocate

Cha-Chi Gibson keeps a photo of her brother Louis Gibson on her coffee table in New Orleans, Wednesday, May 31, 2017. At the age of 17, Louis Gibson was arrested. He was sentenced to life without parole after he shot someone he grew up with. Gibson is now 41 and the Louisiana legislature is looking at a possible 300 other juvenile lifers including Gibson to receive a chance at parole.

“I’m not trying to defend what happened,” she said. “But there wasn’t no opportunities around there. We didn’t even have playgrounds. We stayed down the street from the jailhouse. And everybody that I know that went to jail, went there because they were in the streets, trying to survive.”

As Gibson got older, he tap-danced and shined shoes in the French Quarter. He recalled how, when he was a student at John W. Hoffman Elementary, a teacher named Mrs. Gabriel asked students to write about whom they admired.

Louis, who was a good student, wrote how he wanted to be himself. He got an A. Several years later, when he ran into his teacher, she remembered the essay. He was the only student of hers to ever take that tack, she told him.

His essay may have been well-crafted, but it wasn’t true. “In actuality, I wanted to be like the neighborhood drug dealer,” he said. “But I didn’t want to write that in my paper.” In his everyday world, working for that dealer seemed like his only chance for economic stability.

Within a few years, Gibson had become a small-time drug dealer who hung out with a group of teens on Gravier Street. Several blocks away on Palmyra Street, another group of teen drug-slingers hung out, including his junior-high classmate Terrance King. Socially, the two groups traveled as one.

Ali Sardar/Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

Terrance King, a friend of Louis Gibson, was also shot but survived. "I was part of what went wrong with all of us,” he said.

“If we went to a party, we all went together. We grew up together from 2 or 3 years old to 15 and 16. We knew the same people and we went to the same schools,” said King, now a 40-year-old theology student living in Atlanta.

Recently, because of Senate Bill 16, King finds himself recalling their tumultuous childhoods. “When I reflect on our time in junior high, I see Louis’ face, but I cannot hear any words. That’s how reserved he was,” King said.

Bullets fly

That night, King sat next to the car’s driver, his friend Latrone Davis. Another car of friends followed in near-gridlock traffic near the popular bar, which sat in a desolate corner near a railroad and highway overpass.

At first, everyone was cordial, King said. Davis honked the horn and hollered at Gibson, who stood nearby, outside a Popeye’s chicken franchise. Others yelled out the window, “Hey, Louis, how you doing, Louis?”

But earlier, someone had told Gibson that Davis and the others in his car were armed and prepared to kill him. Terrified, he aimed his gun and pulled the trigger.

As bullets flew, King raised his left arm to shield his face and caught a bullet in the wrist. Next to him, Davis was hit by seven bullets that tore up his chest. Two other friends were also shot, in an arm and a leg.

The shooting had all the hallmarks of impulsive, adolescent thinking and peer pressure. Even the hard line typically drawn between victims and perpetrators can seem senseless when teens hurt those around them, who are often friends and peers. So, after a few years of not talking, King and Gibson made amends.

Now, King hopes to see Gibson released. “Not so much because he was a juvenile. But because of his character,” King said. “And because when I look at the bigger picture of what happened, I feel like I was part of the injury. I was part of what went wrong with all of us.”

Ali Sardar/Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

Terrance King, now a 40-year-old theology student, in his home in Atlanta. "I feel like I was part of the injury," he said.

‘Let him go’

After the shooting, Cha-Chi, who was then 16, knocked on a nearby door and talked with Latrone’s mother. “That little girl came to me and cried,” said Linda Davis Williams, now 61. She appreciated the apology, though some people thought she shouldn’t have allowed Cha-Chi in her house.

“But they were all friends. That’s the worst part about it,” said Williams, who worked as a cook and fed many in the neighborhood, including the Gibson children.

Williams mourned hard for a few years. “Latrone was my first-born. And he was so pretty,” she said. “Big, 6-foot 4. He was calm, a peacemaker, and he was protective of us.” Though it seems morbid to her now, she questioned Latrone’s friends about his dying moments: “Tell me what he said: Did he cry? Was he in pain? Did he call out for his mother?”

She stopped eating and became terrified about the safety of her other children. She’d walk them to school each morning and wait for them outside at the end of the day. And she was angry, so angry.

But over the years, her feelings have softened. “I never thought I’d say this. But I think it’s time to let Louis go,” she said. “He was a child. He made a mistake. But no matter how long they keep him, it’s not going to bring Latrone back.

“If you get a chance to talk to Louis, please tell him I’ve forgiven him years ago,” Williams said. “If I can do anything to get him out, I will do that. Please, please let him go, with my blessings.”

The story is a partnership among the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, a national news site that covers the issue daily; The Lens, a nonprofit, in-depth newsroom in New Orleans; and The Advocate, a daily newspaper serving Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana.

This post has been updated.