“Everywhere we go, people want to know who we are, where we come from, where we’re going, so we tell them, we are a family, a diverse family, a mighty, mighty family, headed to Albany, fighting for justice …”

NEW YORK — The civil rights marchers had gone about a mile and change into Wappinger Falls, a quaint village in Dutchess County, New York, when it was time for a bathroom break.

“Sometimes,” one of the marchers joked, “you need to take a bathroom break for justice.”

The three-vehicle caravan of a ramshackle school bus, a 12-foot Penske moving truck and a Toyota FJ Cruiser that had followed the marchers from Harlem all pulled to a stop at the curb.

The marchers had been walking for about an hour on a bleak and unseasonably cold and rainy September morning without incident when they decided to stop at a coffee shop along Main Street. A handful had been on foot from the starting point in Harlem on an 180-mile walk to Albany, New York, in an attempt to draw attention to the abuses in state prisons and, they hoped, bring about some reforms. Others had just joined the group a few hours ago.

The marchers had been walking for about an hour on a bleak and unseasonably cold and rainy September morning without incident when they decided to stop at a coffee shop along Main Street. A handful had been on foot from the starting point in Harlem on an 180-mile walk to Albany, New York, in an attempt to draw attention to the abuses in state prisons and, they hoped, bring about some reforms. Others had just joined the group a few hours ago.

A few of the marchers, a mix of white and black, young and old, gay, trans and straight, went inside the coffee shop to grab a hot drink to warm up They were a bedraggled bunch. Many had slept the night before on cots and inflatable mattresses in the sanctuary of a nearby church. So the warm, dry Ground Hog coffee shop was a welcome relief.

Stepping into the shop felt like stepping back in time to Mayberry or some other small-town idyll, aside from the cleverly named espresso drinks on the chalkboard like dirty chai latte or coconut moka. The chessboard-tiled floors, wooden tables and framed black-and-white photographs all had the feel of a timeless bit of Americana.

The customers, all of them white, lifted their heads up from breakfasts of French toast and omelets to observe the wet group of marchers ambling past, wearing a quote from Fyodor Dostoyevsky on the back of their T-shirts. It read: “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.”

As the marchers lined up, the opening piano riff of Lynard Skynard’s “Free Bird” came over the speakers. The man taking orders came out from behind the slatted wood counter and approached a 30-year-old black woman, one of the march’s organizers.

“You all need to leave,” he said. “You all need to get out. Now.”

“Why is that?” Lilly Oseitutu replied in a lilting London accent.

“We’re busy and can’t have you blocking up our establishment,” he snapped back.

The two squared off in the middle of the cramped dining room. Ronnie Van Zant sang, “If I leave here tomorrow, would you still remember me?”

“I don’t understand,” she replied making a deliberate effort to remain calm. “We’re paying customers. Why would we have to leave?”

The counter man was in no mood for an argument and shook his head.

“I want you back outside now,” he said.

“We’re not leaving,” she replied.

The man held his ground for a few beats, then shook his head in disgust and returned to his station behind the counter.

The woman went to the bathroom and left the shop a few minutes later.

“You’re damn right I’m not leaving, I’m a paying customer. What does he think this is?” she asked no one in particular. The patrons watched as the door shut behind her and “Free Bird” reached its rousing final chorus.

“Lord knows, I can’t change, Lord help me, I can’t change ...”

The march’s origins

When Soffiyah Elijah, the march’s leader and chief organizer, hears about the incident inside the coffee shop she is not surprised.

“Remember when I told you we were heading Up South,” she said. “This is Up

South.”

Elijah lifts her red megaphone to her mouth and leads the group in a new chant. They have a long way to go yet.

The nonprofit organization she founded and is executive director of, Alliance of Families for Justice, came up with the march. Here is an incomplete list of some of the abuses behind prison walls she is hoping to end. She has them printed on a pamphlet with a pair of black hands in handcuffs on one side and a white hand clutching a billy club on the other: Waterboarding. Mangled ears. Plastic bags held over prisoners’ faces. Teeth kicked out. Prisoners shackled and thrown down flights of stairs. Years spent in solitary confinement.

Lilly Oseitutu yells into megaphones during the March for Justice.

When the nation saw students punched and kicked for trying to integrate lunch counters, or marchers going from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, Alabama, hit with billy clubs and tear gassed, it was outraged. That led to two signature pieces of civil rights legislation.

But, Elijah said, New Yorkers remain indifferent to the savagery in the state prisons that line the march’s route to Albany. That’s why she self-consciously borrowed from an effective civil rights tactic from the 1950s and 1960s. She wants to get people to see that the injustices plaguing the modern criminal justice system have parallels to the past. She sees a profound disconnect between how people lionize the work done in the civil rights movement but remain oblivious to the need for one in present.

It’s a paradox that frustrates Elijah and many who have dedicated themselves to the work of making reforms to the state’s criminal justice system — from the juvenile justice system to adult prisons. She, like many activists and advocates for juvenile justice reform and ending abuses behind prison walls, gets frustrated that the public does not see this as an urgent civil rights catastrophe going in New York state. It’s a partisan issue at best that gets bogged down in predictable policy debates in Albany.

All the while, people like Elijah, the alliance board and its members, made up mostly of volunteers who have seen firsthand what happens behind bars in New York state or who have family there now, watch as children and adults, a staggering number of them black and brown, get beaten out of sight in one of the prisons nestled deep in the bucolic woods and farms of the Hudson Valley.

She thinks the 21st century is in as desperate need for a civil rights movement as the 20th century was, and that the work started then is not done. It’s something she learned working as a defense attorney for decades.

“I started to grasp what my client’s families were going through,” she said. “Particularly mothers and spouses, mothers and partners, fathers and what they were going through. And the agony that they experienced having someone incarcerated. And they would suffer in silence, there was nowhere for them to go, there was no organization, there was nothing. They wouldn’t tell their pastor, they wouldn’t tell their fellow parishioners, frequently they wouldn’t tell other relatives. They would say, ‘Oh Johnny went down South to visit his relatives,’ but like I said, Up South.”

Elijah first stepped into a New York prison because she was in love. She was 17 and her boyfriend was in Auburn Correctional Facility. He was a few years older and was in for a drug charge. His older siblings had already died of heroin overdoses. Elijah was a freshman at Cornell University, an elite private school about 30 miles from the prison. She scheduled her classes so she would have Thursdays free.

“He was someone that I knew that I cared about,” she said. “So I went.”

On her class-free days she would go to the Greyhound station, take the bus to Auburn and visit him.

“I didn’t tell anybody,” Elijah said. “My parents went to their grave never knowing.”

Although she didn’t know it at the time, she said, those visits to the prisons were making a mark on a teenage girl that would shape the lawyer, prison reformer and civil rights advocate she would become.

“What struck me was that everybody in the visiting room being visited looked like me, and all the guards looked like you,” she said, motioning to a white man. “And that was really stark to me, really stark.”

Elijah explained the origins of her brainchild, the March for Justice, sitting on a beat-up metal chair at a rickety foldout table in the lobby of the Unitarian Universalist church in Poughkeepsie, New York. Just down the hall in the sanctuary is where she would be spending the night with the rest of the marchers.

“The other thing that was stark to me was that I saw so many people from my neighborhood in that prison who I had thought had gone down South to visit relatives. I didn’t know they had gone Up South.”

Elijah’s Alliance of Families for Justice is dedicated to ending abuses behind the walls of New York state prisons and helping families of prisoners on the other side. She conceived of the March for Justice, a 180-mile walk from Harlem’s National Black Theater to Albany’s Capitol Building, as a way to be more aggressive in getting out the message of prison abuse.

She witnessed those abuses first-hand while she was the executive director of the Correctional Association, from 2011 until last year. It is the only private organization in the state with the legal authority to access prisons. The legislature granted it the authority in 1846 to inspect prison conditions and report back to the public.

But Elijah felt the association wasn’t doing enough for families, so she founded the Alliance to support incarcerated people and people with criminal records, and their families. Its purpose is also to mobilize people to put pressure on the political system to make sweeping institutional change. That was part of the inspiration for the March for Justice.

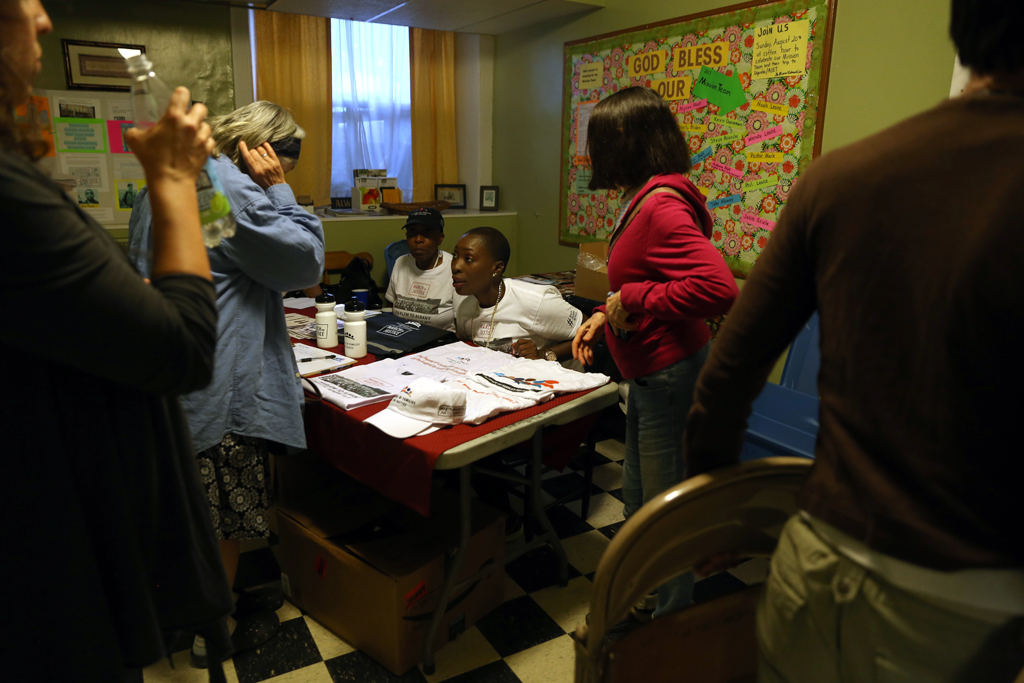

Soffiya Elijah and Lilly Oseitutu sell T-shirts and other merchandise before an evening event.

“When you are trying to move people you have to deal with their hearts and minds, and you can’t do hearts and minds on the phone,” she said. “You have to literally bring it to their living rooms, or at least to their neighborhood — the March for Justice brings it to people’s neighborhood, it brings it to their churches, their houses of worship.”

Justice, but first forms and stretches

It’s not even 9 a.m. on Sunday morning and Lilly Oseitutu in her second church. She describes herself as the “co-logistical coordinator of the whole damn thing.” She walks around the lobby with three clipboards with forms for new arrivals looking to join the march. One is for an emergency contact in case anything happens on the way.

After all the new arrivals fill out their forms they head into a wide hallway of the Beacon Light Tabernacle Seventh Day Adventist Church. Oseitutu takes a head count — 15 will march today — and turns the crowd over to Elijah. Outside it’s gray and overcast with a cold steady drizzle. Elijah speaks the letter “S.” Bill, who wears a long scraggly beard and camouflage and seems like a veteran of the civil rights battles of the 1960s, leans toward a newcomer and whispers, “When Miss Elijah says ‘S’ it means be quiet.”

Elijah turns to the group and flashes a broad, warm smile.

“Welcome to the March for Justice,” she said. “We’re scheduled to do 14 miles in the rain!

“I’m going to start with the importance of following leadership. Oseitutu and I call all the shots. When in doubt,” and then she paused and corrected herself. “I’m not even going to say the word doubt. Just ask us. If anything comes up — ask. If we say get off the road and on the bus, you will get off the road and onto the bus.

“We have a long road ahead of us. There will be times when you can’t be heard and we’ll say reserve your voices and just march. And when we say that, just march.”

After she laid out the importance of leadership, it was time for chi. Every morning Elijah leads the marchers in a series of stretches designed to get people’s chi going. She jokes that you can’t get justice without the chi. After series of twists, toe grabs and leg stretches it’s time to hit the road.

“This is a good time for a bathroom break because we don’t know where the next bathroom will be. So now is the time!”

Bathrooms, snacks, potential allergies volunteer marchers might have, roads with shoulders, alerting police departments, routes, alternative routes, places that will have outlets to charge phones, accommodations, sleeping arrangements, laundry — when you spend a few days on the March for Justice you get a sense of how much of the work is dedicated to a dizzying array of minutiae, tasks and navigating around unexpected obstacles that pop up, both major and minor.

Everyone climbs on the bus. Elijah is riding in another of the caravan vehicles. But she gives some final words of wisdom from the doorway.

The drivers of the March for Justice caravan watch the marchers from a parking lot.

“Our goal is to be what?” she asks the passengers. They look back blankly. Elijah nods. “To be safe!” She flashes a mischievous grin. “If you get a little anxious, sing ‘The wheels of the bus go round and round’!”

Bill turns the key, the bus makes a loud wrenching noise and rumbles to life, headed to the next spot where the organizers have found a safe marching route.

Banners hang from each side of the bus covering the windows. On them are pictures of some of the incarcerated people and their families they are marching to help. The feeble light creates a gloomy atmosphere, but it doesn’t affect the marchers. The mood on the bus is upbeat. A few women are trying to retrace yesterday’s route on a map.

Another clutch of newcomers are engaged in lively chat, the kind of conversation you expect out of strangers who just met in a church lobby at 8 in the morning. Miss Ivey, the oldest member of the group who has been with the group since they left Harlem on Aug. 26, is napping. Her son has been in a New York state prison for two decades. She calls him daily to keep him updated on their progress.

Bill pulls the bus into a Valero gas station in Wappinger Falls about nine miles outside Poughkeepsie. Kevin Barron, the media coordinator, stand up and shouts: “OK, everybody off!”

The marchers gather gear. The banner carriers work out the best way to hold them so they can be seen by passers-by. Elijah makes sure everyone has a poncho as the rain continues to steadily fall.

“Hey, does anyone want a megaphone,” one marcher shouted to the crowd. “I have two,” she said, raising the bright red amplifiers in the air.

They’re on the move.

Elijah lifts a megaphone to her mouth and shouts the first of dozens of call-and-response chants she will lead that day:

“One, two, three, four! Tell me what we’re marching for,” she says, almost singing the words. “Five, six, seven, eight! An end to the prison state!”

A car zooms by honks and waves. Elijah doesn’t miss a beat as she smiles and waves back.

Hot soup and a new home for the night

After Oseitutu’s showdown at the coffee shop, the rest of the march goes without incident. A few people roll their windows low enough to voice their displeasure. But most of their reception is positive, with people scooching their windows down to wave. The afternoon turns into a torrent and Elijah decides to drive the remainder of the day’s route. Everyone piles back in and Bill delivers them to a Unitarian Universalist church.

Everyone forms a bucket brigade and helps haul in all the supplies from the Penske truck. Once everything is inside the church, people settle in for lunch. A pile of brown bags sits on one table, and two pots of steaming soup sit on another. Volunteers made homemade chicken noodle soup and veggie and bean wraps. Stickers are on the foldout tables with bold black lettering that read: #Feed the Resistance.

Elijah calls out “S” and the room falls silent. She tells everyone what’s on the menu.

“The lunch is vegan, the cookies are not,” and then she starts singing it, as she would a march chant.

During lunch many of the participants talk about what brought them out to join the March for Justice and walk in a cold, dreary rain. Chaia Lehrer, a member of Mid-Hudson Jews for Racial Justice, explains it with a picture she recently took.

The March for Justice went on despite the rain.

“It’s totally off the road, it’s way back behind the woods,” she said, almost with an air of paranoia. “That’s how they do it. They hide it back in the country so no one can see it — so no one knows.”

Lehrer pulls out her phone and pulls up a photo. It is a picture of a sign. Highland Residential Center Office of Children and Family Services. It’s a juvenile center that was at the heart of a 2010 lawsuit for numerous abuses.

She pulls up another. This one is a picture of a nondescript building behind a fence ringed with barbed wire.

“Who knows what’s going on in there,” she says in a whisper.

Lehrer explains that her main frustration is that the children in the facility have no connection to the community in the surrounding area, and the community has no connection to the children. There is no incentive, she said, for anyone in the community to care about what is happening to the children imprisoned behind the gates.

“There are no kids from around here in there,” she says with a dismissive wave. “These are all kids from the city. The community has no connection to what is going on in the facility. Their parents are too far away to know. It’s a very bad situation.”

She pointed to the members of the march scattered around the sanctuary.

“This is the civil rights movement,” Lehrer said. “This is just the next phase of the civil rights movement. This is how civil rights abuses happen now. Locking people up, putting them under supervision. Making a whole new class of people with no rights.”

Jake Salt agrees that the March for Justice is at the heart of a burgeoning civil rights movement.

Salt, 31, said he first realized that the criminal justice system was broken when he got arrested for a prank gone wrong when he was a teenager, in the early 2000s. Salt and two friends were in the Youth Detention Center in Passaic, New Jersey. Salt, who is white, was in a holding cell awaiting an appearance when another teenager, who was black, approached him. Salt remember the black teenager yelling at him that he and his two white friends were going to be out of here and that everyone else in the cell would be stuck in jail.

“He was right,” Salt said, talking in the Unitarian church’s sanctuary after lunch. “The three white kids went home. All the black and brown kids stayed in jail.”

Growing up white and middle class insulated him from the pipeline that eventually funnels many black and Hispanic children into the adult prison system, he said.

“I was able to go through a year of probation and live my life and not be exposed to recidivism,” Salt said.

The experience forever changed his worldview. Salt, who now runs the Hudson Valley LGBTQ Community Center, dedicated his life to activism because of that day in the court. He said it was important for him to come out and show solidarity with the March for Justice because so many LGBTQ, especially youth of color, are vulnerable to the juvenile justice system.

“Sure, I’m in this Universalist Unitarian church sitting being able to feel great about being able to go and march and make a difference, and that’s fine,” he said. “But there’s a lot of people out there who could be doing the same thing but they didn’t have the chance because the way they looked sent them down a different path.”

After the volunteer marchers who just signed up for the day leave and only the hard-core marchers remain, Elijah places a computer on one of the lunch tables and plays a video from the day before. It shows the march going past the Fishkill Correctional Facility. An administrator comes out and tells them to leave. They refuse. Oseitutu and the administrator get into a heated argument. As they go back and forth, corrections vehicles race past in what appears to be an attempt to intimidate them.

Jake Salt hangs out at a Universal Unitarian Church after marching from Beacon to Poughkeepsie, New York.

Miss Ivey, the oldest member of the group at 82, has a son serving time there. He is 55 and has been inside for two decades. She talked to him on the phone later on. He told her he couldn’t hear them. She counseled him not to mention it to the other inmates. She was worried that the word would get out and her son would face retribution from the corrections officers.

Day 9: Next stop, New Paltz

The next morning is the same as the one before. More forms, a head count, more channeling the chi. Elijah warns the new marchers to be polite and not get into any skirmishes with anyone who might disagree with their message along the route.

She points to Miss Ivey. “Miss Ivey is here to make sure there is no counter-revolutionary activity,” she tells them, smiling. “If anyone gets out of line she is here to straighten them out.”

During breakfast, a heated argument breaks out among a few marchers about the best way to persuade people to their cause. One argues for direct action and confrontation, the other for persuasion. They agree to disagree.

Everyone is ready to go by 9 a.m. They file out with Elijah at the front. As the marchers make their way up the church driveway and down a narrow sidewalk a few step on someone’s lawn. Elijah cautions them to be careful.

“We don’t want to disrespect anybody’s property,” she tells them. “So please go single file.”

They are headed for Hudson Valley Rail Trail. After conferring with Oseitutu and Barron, Elijah decides that since it’s Labor Day they will be able to reach a lot of people with their message. She is concerned because this will be the first time the caravan won’t be by their side. The trail doesn’t allow cars. But, it's a warm and sunny day, and she expects there to be a lot of people out.

Soffiya Elijah (third from left) negotiates with a Park Department employee (far left) about marching across the Walkway Over the Hudson in Poughkeepsie.

While they are walking along Hooker Avenue, a white man in another pickup truck slows down and honks to get the marchers’ attention. Then he stuck his hand out the window and gave them the middle finger.

“We’re getting mixed responses,” Oseitutu said. “Very mixed responses.”

It is a sign of things to come.

First the march enters downtown Poughkeepsie, where Oseitutu said she has encountered more resistance to the message since they left Harlem. She has been darting back and forth across the street handing out fliers. She goes into businesses like a barber shop and Dunkin’ Donuts and makes her pitch.

Oseitutu tries to give a flier to a woman but she refuses.

“Black people kidnapped my kids,” she shouts. “You got to stop doing what you’re doing!”

“It’s to be expected,” Oseitutu says as she hustles across the street to hand another passerby a flier. “The further we head upstate we go, the more we are going to be encountering people who are resistant to our message. But I have really been feeling it today.”

When Oseitutu recounts the encounter with the woman to Elijah, she flashes a sardonic smile.

“Black people kidnapped her kids,” Elijah said sarcastically. “White people kidnapped my family. Did you say that?” she asked Oseitutu.

“No,” she replied. “I should’ve said that.”

“Listen,” Elijah said. “We don’t want to have a lecture about kidnapping.”

One of the marchers taking part from Poughkeepsie to New Paltz, New York.

Taking the scenic route for justice

It doesn’t take long along the Rail Trail, a pedestrian trail that has a bridge that spans the Hudson River offering a stunning view, when they encounter their first obstacle. After a bathroom break at the port-a-potties and guzzling some water in the shade, they make their way to the bridge but are stopped by a Parks Department worker driving a golf cart.

“Who’s got the permit, you can’t march without a permit,” she says with finality.

After some initial confusion, Elijah approached the parks employee.

“I called the police station in the area and alerted them that we were coming and that we would be coming through.”

The employee starts shaking her head before Elijah can finish her sentence.

“There’s going to be no marching today,” she said. “Not without a permit.”

“Well,” Elijah said with a weary smile. “I’ve been marching all the way from Harlem. I’m not turning back.”

The two women stare at each other. After a few beats, the mechanical, officious bureaucratic demeanor of the parks employee melts away and her off-the-clock personality comes through.

“All right, listen,” she said. “You all go ahead and march. Just try to keep it to one side and watch out for the bikes.”

Can we chant, one of the marchers chimes in. The question hangs in the air for what seems like an eternity. For a second it seems like the hard-won victory may be derailed. The emotions that play across Elijah’s face make it evident this was a rookie question. Seasoned protesters know you never ask for permission.

The parks employee takes a deep breath, sighs, drops her chin to her chest and nods.

“Go ahead, chant,” she said. And then she leans forward and whispers to Elijah: “Keep up the good work!”

Crossing the Hudson

The small victory rallies the marchers, and they need it. They have logged about 5 miles under a bright sun and seem tired. All except Elijah. On the March for Justice she is equal parts drum major, singer, coach and CEO. At the front of the march she appears to fall into a reverie, slowly nodding her head and moving like a dancer, crouching with athletic ease.

Elijah gets the marchers organized and has them shouting another chant. She waves and beams a huge smile to visitors on their Labor Day strolls who gawk at the marchers navigating the crowds. Meanwhile Oseitutu and Ray Ray are sprinting up to people, handing out fliers to anyone who will take them.

Ray Ray, 42, a black activist from Poughkeepsie, approaches a white man along the trail and tries to hand him a flyer. He refuses. “Ninety-five percent of all the people in there deserve to be in there,” he said. “They’re all killers.”

Ray Ray politely disagrees and points to some of the facts on the flier. She then points out the Alliance for Families for Justice website, which has information and data on New York state prisoners. He does not show any interest.

Ray Ray tries another tactic.

“If you think that people who are killers or hurt other people should be put in prison, you should be marching with us. That’s what we’re fighting against. These prisoners are getting beaten and tortured and sometimes killed.”

A marcher comes out of a coffee shop where she stopped to use the bathroom.

The man does not agree. Ray Ray thanks him for his time, joins the chant and jogs to catch up with the march.

Another white man shouts at Oseitutu: “Can you please keep moving? We’re trying to enjoy our Labor Day.”

Oseitutu responds politely but forcefully.

“Actually, we have as much right to be here as you do,” she said. “So sit there and listen.”

Jayme Schultz, 38, who is white, had not planned on marching. She was out on a leisurely walk with her son on her shoulders when she noticed Oseitutu enthusiastically handing out fliers to passers-by. She changed her route and joined in the march from the rear. After a few paces she started joining in the chants.

“I saw them and it seemed like the right thing to do,” she said.

Schultz talked about a friend who was teaching behind the walls of a local prison. The administration would constantly sabotage her efforts to do her job, the friend said.

Jayme Schultz and her son Arthur joined the march on the Walkway Over the Hudson for a while.

“She came out of that experience completely changed,” she said. “She saw lots of abuses and the corrections officers treating the prisoners so badly, calling them racial insults. She said they were treated so poorly.”

Schultz said she had no doubt that the abuses in prisons and the racial inequities in New York’s criminal justice system represent a civil rights crisis.

“Absolutely,” she said. “That’s why it’s such a good thing these marchers are out here. You need to make people feel uncomfortable. They live their comfortable lives and they aren’t touched by any of the horrors that are going. You need to make them feel uncomfortable. You need to put it right in their faces where they live, where they go for their Labor Day walks.”

When she got across the bridge she stopped. She had a long walk ahead of her to get back home and needed to get her son lunch. Arthur, still on his mother’s neck, craned his neck to watch the marchers head off into the distance.

“I want to go,” he said in a disappointed voice.

“I know you don’t want to stop, you want to keep going,” Schultz said in a reassuring tone. “It’s OK, buddy, we’ll be able to join up again some other time!”

Not a safe route

After they cross the bridge and head farther north on the trail, the crowds diminish. They are now walking through towering woods that occasionally create a canopy with dappled light on the path. Elijah announces there won’t be any more chants until they reach a more dense area.

“I want you to conserve your energy,” she tells them.

The marchers slow their pace and chat among themselves, recalling some of the encounters they’ve had along the way.

There are exercise stations set up along the trail. One of them has a sign mounted that reads: Hamstring Stretch. Ray Ray sees it and gets excited.

“Oh man, hamstring stretch, I need that,” she said.

She jogs over and slings her leg up one of the bars and starts leaning in. She groans as she stretches.

“All right,” she said, limbered up. “Time to go.”

Ray Ray takes a stretch break halfway between Poughkeepsie and New Paltz, New York.

About a mile or so later, they reach Tony Williams Park, where another volunteer has lunch waiting. Two big trays of peanut noodles, one with chicken, another strictly vegetarian, and an economy-sized bag of ginger snaps for dessert. There’s a sense of camaraderie among the group. Even though many of them met in a strange church about seven hours earlier, they are laughing, hugging and sharing intimate conversation.

After lunch, Elijah, Oseitutu and Barron spread a map out on one of the picnic tables and assess the next move to New Paltz. The only road to New Paltz from the park has no shoulder. Elijah decides it’s too dangerous and tells Bill to get the bus ready.

Elijah explains to everyone that they need to drive the next few miles. They look visibly disappointed. They relish hitting the pavement. But Elijah is insistent.

“It’s just not a safe route,” she said.

New Paltz is where Elijah is scheduled to meet a 105-year-old named Journey Truth.

She wants to join the march.

The road to New Paltz

The mood turns at New Paltz. More people join the marchers as they make their way through downtown. At the head of the march is Elijah, trotting backwards, shouting one of her favorite chants:

“Everywhere we go, people want to know, who we are, where we come from, where we’re going, so we tell them, we are a family, a diverse family, a mighty, mighty family, headed to Albany, fighting for justice …”

Right behind her, singing along, are Miss Ivey and Journey Truth, a local, a former artist and activist who insisted on joining the march. She is being pushed in her wheelchair. Miss Ivey stands next to her, clutching her walker. The crowd is as big as it has been in days and the sidewalks are narrow.

The road is steep and they have to be careful. Miss Ivey and Journey Truth are determined. They find each other in the scrum of the march and reach out for each other. They clasp hands for a brief moment and look at each other while they sing.

Truth can’t make it to the end of the march. She is wheeled back to her car, where a marcher and her caretaker gently guide her into the passenger seat of a car.

“She’s 105 years old; she’s seen everything,” said Amy Trompetter, one of the many friends of Truth’s who care for her. But, she added, Truth is horrified by what the prisoners in New York endure. “She is going to leave the planet soon. She knows this. But she’s determined in helping to lead the struggle.”

Journey Truth, 105 (in wheelchair), and Miss Ivey, 82 (using walker), march down the streets toward New Paltz, New York, with the March for Justice.

Unfinished business

The gloom that had settled on the group after the run-ins in Poughkeepsie has lifted as they make their way through historic New Paltz. As they approach the Reformed Church of New Paltz, they can see a huge crowd waiting for them. The crowd is jubilant, cheering them as they make their way into the driveway. The front lawn is covered with picnic tables that have spread out on them farm corn, casseroles, potato salad, burgers, hot dogs and a variety of homemade treats.

A celebratory feeling is in the air. Miss Ivey gets a burger and a hot dog, a little squirt of ketchup and mustard on each. Miss Ivey lives in the East New York neighborhood in Brooklyn, but was born in Selma and moved to the Florida Panhandle town of Pensacola when she was still a toddler. She still spent many of her summers in Alabama growing up, and said her time there had had a big influence on her.

“Now, when we were in the South, white people were the ones who taught their children there was a difference between black and white,” she said, munching on her burger. “Preaching hate at the dinner table. Black people didn’t do that. They just told us to be careful. They just told us what to be careful of. They never taught us to hate.”

She recently went back to Alabama to visit Edmund Pettus Bridge with seven of her grandchildren. But she said, civil rights isn’t a chapter to be relegated to a stale history book. There is no doubt in her mind that the March for Justice is part of a movement.

“It’s civil rights, it’s human rights, it’s the whole nine yards,” she said. “The brutality shown to the inmates. There’s no reason for a human being to be treated that way, to be dehumanized. What we’re marching for is unfinished business from the old days.”

A huge gust of wind blows through, knocking over some cups and causing a minor commotion.

“The wind is telling us,” Miss Ivey said. “We got to get moving.”

Bill helps escort Miss Ivey down the stairs to the basement. Elijah, Oseitutu and Kevin Barron are already there, converting a foldout table into a makeshift information booth. They stack their literature in neat piles and arrange their merchandise. After they’re done, they sit and relax for a moment.

Barron looks at Oseitutu.

“Tired?” he asked.

“I could sleep for three days,” she replied, hanging her head with exhaustion.

Barron, 62, arches his eyebrows and looks puckish.

“How old are you?” he asked.

“What does my age have to do with anything,” she shot back. “I’ve just marched for nine days. I don’t care how old I am, I am going to be tired.”

“How old are you?” he asked again.

“I’m 30,” she said. “Were you doing 19-day marches when you were 30?”

Barron leans back in his chair and waves his hand dismissively.

“I could have marched to California when I was 30,” he responded with a grin.

Elijah, who has been enjoying watching the exchange, chimes in. She turned to Barron.

“Do you remember what you said to me when I said we’re going to be marching from Harlem to Albany?”

“No,” Barron said.

“You said, ‘Who?’” Elijah responded. “‘We’ is a plural pronoun last time I checked.”

The anecdote has them all laughing, but it’s short-lived. Moments later, people coming for that evening’s program are already crowding around the table. They start asking about T-shirts and tote bags, and inquiring about the pamphlets.

The march has ended for the day, but their work has just begun.

Check out previous New York March coverage

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.

Pingback: New York’s March for Justice | Bokeh