POUGHKEEPSIE, New York — When she was in the sixth grade, when she still wanted to be a pediatrician and not a lawyer for revolutionaries, Soffiyah Elijah entered her first integrated school in Hempstead, Long Island. She remembers that in response to integration the administration of the school then segregated the classrooms. So she spent her first day in an integrated school among all black students.

That didn’t last long.

That afternoon after school was dismissed she went home and told her parents.

“My mother marched up to the school the next day,” Elijah recollected. “And she moved her little girl over to the other class. It was like either my daughter will be in this other class or you’ll wish she was. My mother was a no-nonsense mom.”

When asked if she feels some of her mother’s sense of justice helped shaped the woman she has become, she bursts out into laughter.

When asked if she feels some of her mother’s sense of justice helped shaped the woman she has become, she bursts out into laughter.

“I think a lot of her rubbed off on me,” she said. “And my dad was a no-nonsense dad.”

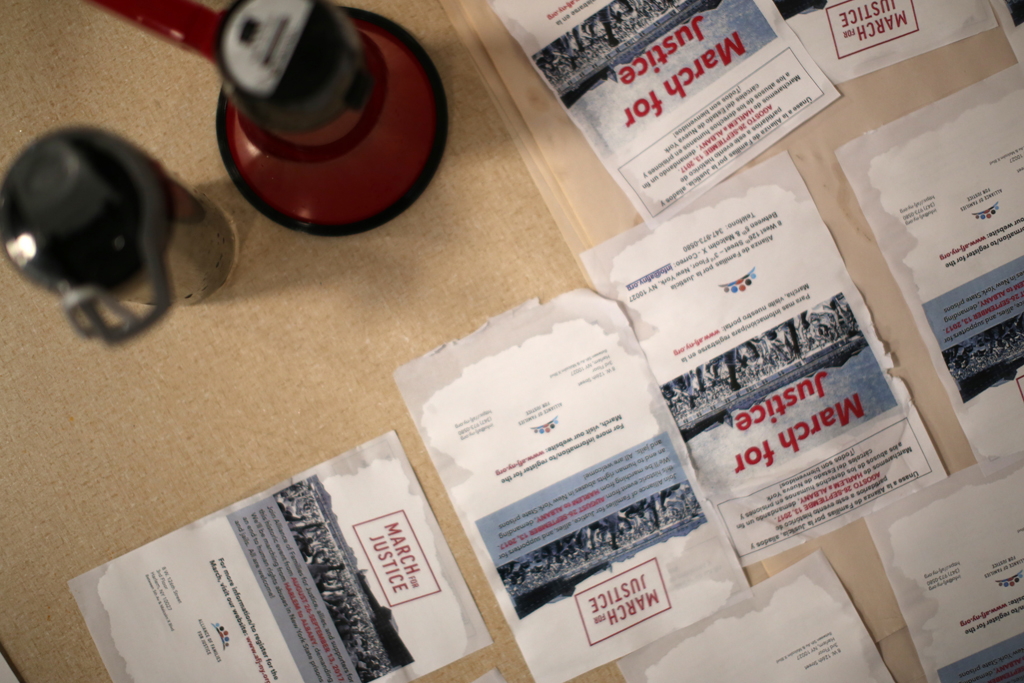

Elijah was looking to explain what inspired her to organize and lead the March for Justice. In order to do that, she reached back to her childhood. She needed to explain the ubiquitous system of segregation that touched her life starting as a toddler.

Major events of her childhood

It wasn’t just her professional life as a lawyer or her work leading the Correctional Association of New York, but a lifetime of exposure to rampant segregation that shaped the 62-year-old to organize a 21st-century civil rights march in the state often considered one of the most progressive in the union. That’s a misconception she hopes to dispel by the time she reaches Albany, New York, at the end of her 180-mile March for Justice.

“The assassination of John F. Kennedy, the assassination of Malcolm X, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, the assassination of Martin Luther King, the assassination of Medgar Evers, the Cointelpro program, the brutality of the civil rights workers that they went through,” Elijah said, listing the historical forces that shaped her youth. “That’s a lot, right, to shape someone’s formative years. I watched the political assassination of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., I grew up when black people were never depicted on television in a positive light. So, it’s rooted in my DNA.”

By the time Elijah had reached sixth grade she had already become inured to the ubiquitous racism that defined her neighborhood. She grew up on the border of Hempstead and Garden City. Garden City was all white back then, but Hempstead was segregated between black and white residents. Her house was near the border of Garden City. So she and her black playmates grew up knowing a lesson that wasn’t taught at any school.

“So I knew,” she said “As black kids growing up there we all knew. ‘Do not ride your bicycle past this block.’”

As a black child in Long Island, segregation was as much a part of her life as someone in the deep South. Elijah grew up hearing her parents tell the story of moving day. Her neighbors were white. Someone had painted “Go Home NIGGER” on the picket fence.

“Now I was too young to see that or to understand it because I was only 2, but my parents, as I got older I would hear them talking about that,” she said. “So, I didn’t have to wait until I got to the sixth grade.”

When her parents took her on trips to Delaware to visit her godmother or farther south into Maryland to visit relatives, Elijah became accustomed to a routine: Her parents would always pack food and a portable toilet. She learned on those trips that because she and her parents were black that they couldn’t use any public accommodations.

“That was just the norm,” she said flatly. “You packed your food; you packed your port-a-potty, and that’s how you traveled. And so I learned that well before I got to sixth grade. The idea of stopping at a rest stop on the road to D.C. to go in and use the bathroom and buy something to eat — I didn’t learn that until I was an adult.”

First step to fix justice system

As the founder and executive director of the Alliance of Families for Justice, Elijah now works with many families with loved ones behind bars. But in 2001 she had her own close call. Elijah’s son was arrested by the Boston Transit Police for a graffiti charge. She attended the court hearing in Boston, but did not reveal she was a criminal defense lawyer who had once taught at Harvard. Her son’s defense lawyer came up to Elijah and told her to relax.

“‘Mom, you don’t have to worry, we’re going to get him six months probation,’” Elijah remembers her saying. “I said, ‘Oh no, you’re not. You’ve got yourself the wrong little black boy.’ And I gave her my card. And I said, ‘Now you fix it or I will.’”

The head of the gang violence unit of the Boston police came into court and swore out an affidavit that she witnessed him doing graffiti at a train station, Elijah said. The headmaster and the dean of her son’s private school went to court and swore out an affidavit that he was in school.

“I’m sure the only reason he didn’t go on the adult track is because he had a criminal defense lawyer as a mother,” she said. “It was like, ‘You are not going to screw up my son.’ If it weren’t for that, I’m sure his life would have been very different.”

She said there is no fixing the criminal justice system without first repairing a broken juvenile justice system.

“I don’t think you can fix mass incarceration unless you address the juvenile justice system,” Elijah said. “And you can’t address the juvenile justice system without addressing the education system. They are feeder systems.”

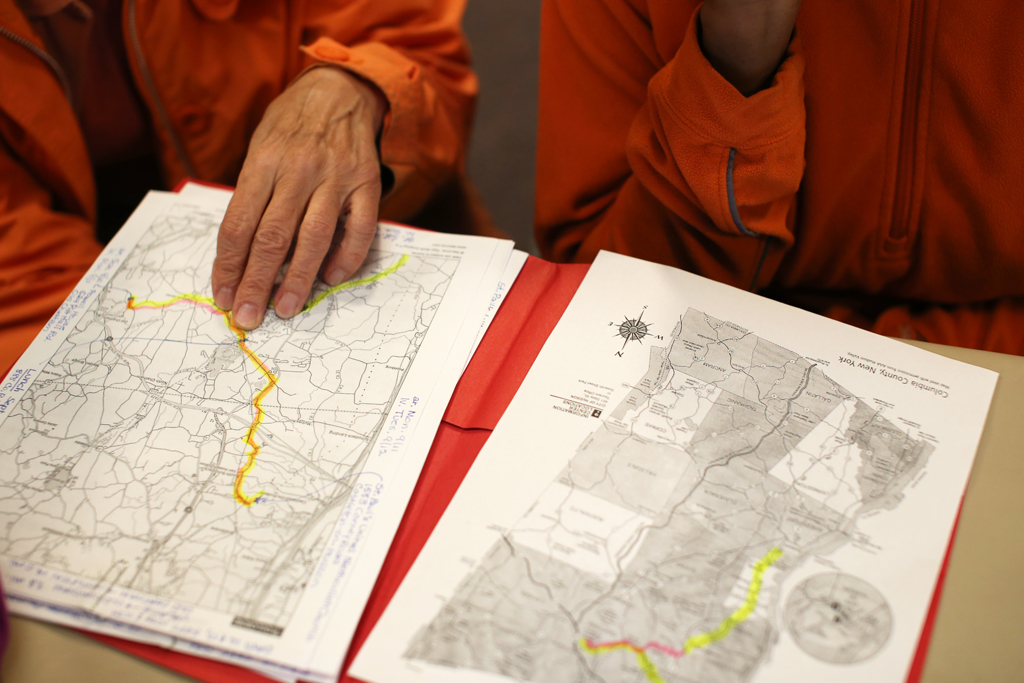

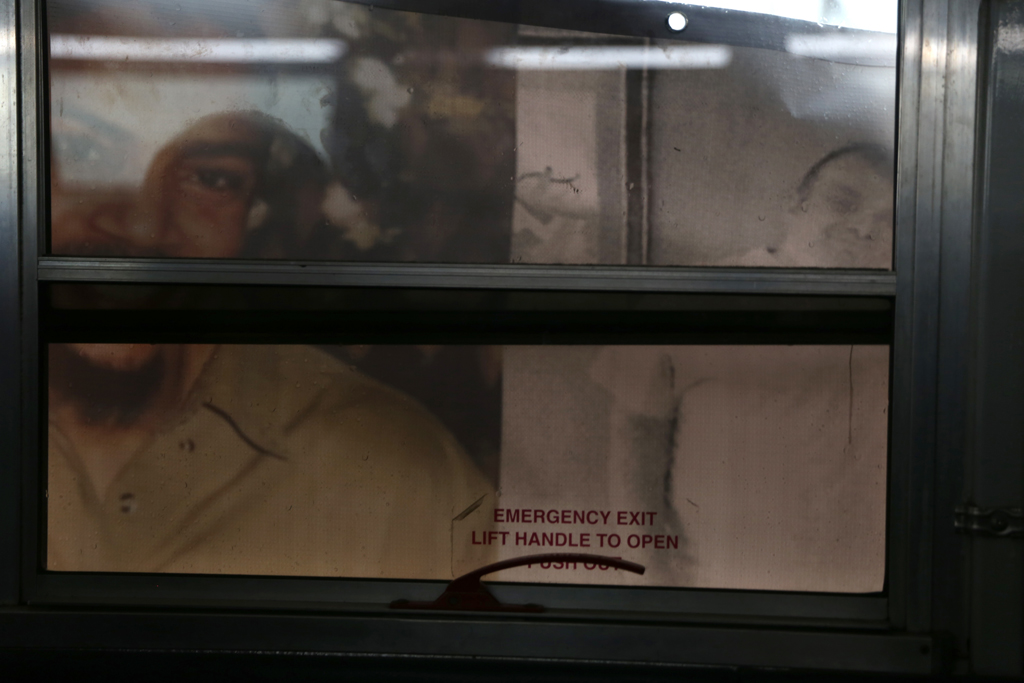

She had just taken a quick cat nap on a beat-up sofa in the lobby of one of the many churches that offered her marchers shelter. She was on the eve of reaching the halfway point between the beginning of the march in Harlem to the terminus in Albany.

She remained steadfast in her belief that this civil rights movement for the 21st century she is trying to jumpstart is essential in influencing a generation of young people to make as big a difference as the activists of the 1960s did to transform the country.

“This is part of how we can touch the next generation. This why I am doing this,” she said. “Lord knows, I could be doing something else at 62 years old besides going down the block in some strange neighborhood with a megaphone, OK? But it’s like a moving classroom. It’s like an interactive moving classroom for young people. And that’s really important. There’s no university they can go to on this planet where they can go to that can teach them this.”

Check out previous New York March coverage

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.