This is part of The Long Wait, a series exploring the Illinois Prisoner Review Board’s process for deciding on parole for a group of inmates who remain in prison for serious crimes committed before 1978.

The crime would send shockwaves through the Chicago police department for decades.

On a summer day in 1970, two Chicago Police officers assigned to the “walk and talk” team, meant to improve relations between police and the community at the Cabrini-Green public housing projects, were walking across a field when gunfire erupted. Surrounded by the high-rise buildings, snipers fired on the men, killing them both.

Police quickly built a case against two young men, who they said were members of street gangs. Johnnie Veal, then 17, and George Knights, then 23, were both charged with two counts of murder and tried together. While there was physical evidence presented against Knights, none directly tied Veal to the crime. Both insisted they were not guilty.

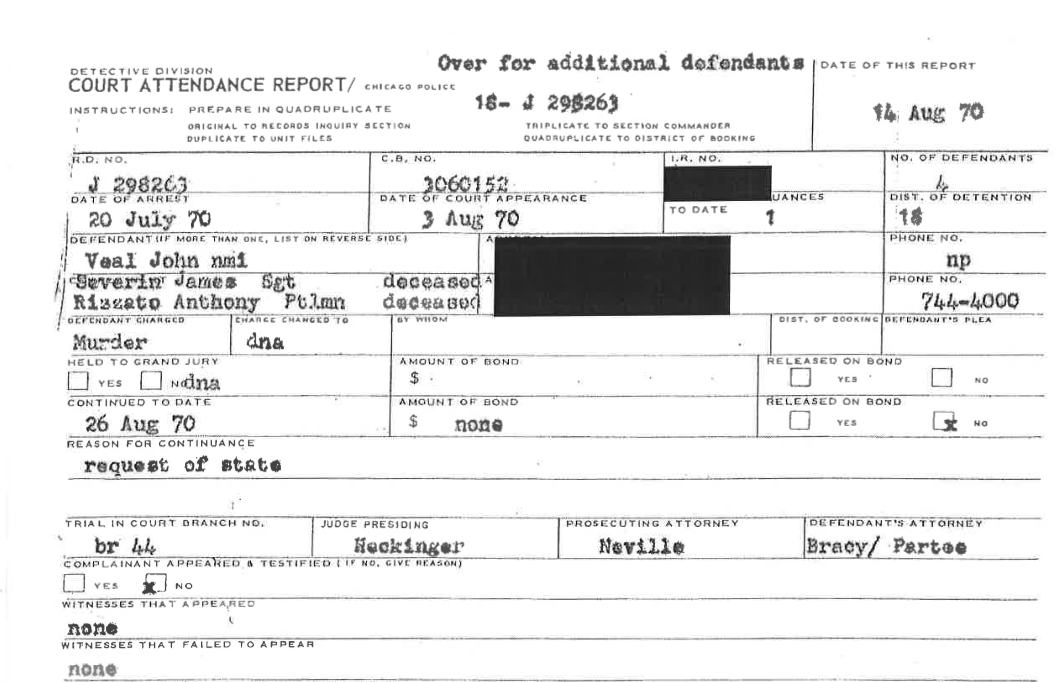

A court report from Johnnie Veal’s murders case from Aug. 14, 1970.

Both were convicted and sentenced to terms of 100 to 199 years in prison with the opportunity for parole. That has left them among the 121 men and one woman at the mercy of the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, which has consistently rejected their efforts to seek parole.

The board’s decisions, an Injustice Watch examination found, are often inconsistent and arbitrary. Veal is among a number of the prisoners who, finding the door to parole shut year after year, have turned to the courts in a desperate effort to win freedom.

Veal filed a petition last year in Cook County Circuit Court contending that because the parole board is not meaningfully considering his release, he has been illegally sentenced to life without parole — a sentence that the U.S. Supreme Court said cannot be automatically imposed under the Constitution on 17-year-olds. Earlier this year, as the board again turned away a parole request from Knights, board chairman Craig Findley commented, “I just don’t see how George Knights or Johnnie Veal could ever be released.”

Veal’s plea was rejected by Cook County Circuit Judge Rickey Jones in July 2016. He is appealing.

The Illinois Supreme Court ruled in 1996 that the board has “complete discretion” in deciding parole, and that unlike other states such as Wisconsin and Michigan, its decisions are not generally reviewable. The court noted that parole board decisions are “often based on subjective factors and predictions rather than objective factors.”

Prisoners in Illinois can only turn to the courts if the board fails to hold required parole hearings — whatever the outcome — or if the board acts in an unconstitutional way, such as denying parole based on a defendant’s race.

While evidence of a defendant’s innocence is critical in court, it tends to work against prisoners seeking parole. Prisoners’ refusal to acknowledge responsibility for the crime — even if they insist they are innocent — is often held against them in board deliberations.

In Veal’s case, a fingerprint of his co-defendant, Knights, was discovered on a box of bullets in a high-rise’s incinerator room after the shooting. Police traced the bullets to a store in Indiana, where Knights signed the purchase slip for the ammunition, according to court records.

David Wilson / Flickr

A photo of the Cabrini-Green public housing projects in 2003.

But there was no physical evidence against Veal, according to court records, and no witnesses said they saw Veal commit the crime. The case against him was built on the word of several witnesses who testified that Veal made statements before and after the murders indicating he was involved.

Three boys, also gang members, were among the key witnesses against him. They each recanted after the trial.

When Veal’s last parole request came before the board in 2014, one factor board members considered was his lack of remorse for the crimes, board minutes show. His supporters tried to justify Veal’s response, saying, “You cannot ask a man to admit guilt for something he did not do,” the minutes show.

The board’s repeated rejection of his parole spurred Veal to try the courthouse. “Time is of the essence,” he said in an interview from Hill Correctional Center. “Tomorrow’s not promised to me, so I’m trying to get the best I can get, to try to get to where I’m supposed to be with family and loved ones.”

In another police killing case, Ronnie Carrasquillo, who was sentenced in 1978 for shooting Chicago police officer Terrence Loftus, also filed a petition in the Cook County Circuit Court stating that he has no real chance at parole because the victim in his case was a policeman. Like Veal, Carrasquillo, who had turned 18 months before the crime, contends that the board’s routine denials have resulted in an automatic life sentence without parole.

Carrasquillo also argues in a separate petition that his hefty sentence was unfairly imposed by a corrupt judge to deflect the sharp public criticism he received months earlier after acquitting mob hitman Harry Aleman in a nonjury trial. At a September hearing on that petition, Carrasquillo’s trial attorney, Glenn Seiden, testified that an FBI agent later made comments to him suggesting a link between those cases.

More than a decade after Carrasquillo was convicted, Wilson committed suicide after the FBI confronted him about evidence that he had taken a $10,000 bribe to acquit the mob hitman. “Only a corrupt judge would have sentenced a teen-aged boy under these circumstances to a draconian sentence of 200-600 years,” Carrasquillo’s petition states.

While Carrasquillo and Veal, among other prisoners, try to overturn their verdicts arguing they were unjustly convicted or sentenced, such evidence carries little weight in their separate proceedings before the Prisoner Review Board.

Legally, the board is required to focus solely on whether an inmate is an acceptable risk for release, said the board’s legal counsel, Jason Sweat. Because inmates have already gone through trial and sentencing, speculating on the quality of trial evidence, Sweat said, is not up for consideration.

Claims of innocence have not always been an obstacle to parole.

In late 2005, the board paroled Duffie Clark, who was convicted in 1971 of slaying two youth on Chicago’s South Side. Clark’s attorney, Dana Orr Williams, said in prior years Clark had not received any votes in favor of his parole. He only was released once she presented information sowing doubt in the evidence of his guilt.

Williams said she thinks her argument and the questions she raised about Clark’s guilt resonated with the board members who voted in his favor. Parole was granted despite his refusal to be contrite, she said, which “did not go over well” with all members of the board. Williams said Clark “wasn’t going to cop to something he didn’t do.”

In other cases, board members cite that lack of contrition as they deny parole. Carrasquillo has long contended he did not intend to shoot the police officer, who was in plainclothes at the time, causing then-board member Angela Blackman-Donovan to comment that Carrasquillo “won’t own up to it,” according to meeting minutes from 2013. She then voted against his parole.

Jeanne Kuang / Injustice Watch

Old photographs show Ronnie Carrasquillo with his family during prison visits. They sit on the mantle in the home of Deyra Mercado, Carrasquillo’s half-sister.

Sitting in a visiting room recently in Dixon Correctional Center, Carrasquillo discussed his plans for a life outside prison. If he is ever released, he would be starting a life when most others his age would be nearing retirement.

He recognizes the struggle to win over the board members.

He has more faith, he said, in being released through the courts than the parole board. “They see me as a lifer,” he said of the board members. “It’s that simple.”

Injustice Watch co-director Rob Warden, who co-authored the book “Greylord,” is being called as an expert to testify about me=dia coverage of Judge Frank Wilson, on behalf of Carrasquillo’s petition. As a result Warden played no role in reporting or editing this series.

This article was written by and originally ran in Injustice Watch.