LOS ANGELES — Kim McGill was only 12 years old when she was first arrested and incarcerated for grand larceny. As a young girl, she had taken order requests from individuals, stolen and sold the items. At 13, she was charged with a felony for the second time and imprisoned in a juvenile detention center for shoplifting more than $1,000 worth of merchandise. After that she was prosecuted for several misdemeanor cases, both as a youth and an adult.

As a former felon and now the lead organizer of the Youth Justice Coalition, McGill is against confinement.

“It's not about fixing the system so people re-enter with more resources,” she said. “It's about knowing that you can't get well in a cell, you can't grow in a cage.”

McGill’s memories still gnaw at her today. She described sleep deprivation due to extreme air conditioning, fluorescent lighting and lack of sufficiently warm clothing. She recalled the absence of any external stimulation: the lack of windows, the inability to see the sky and the deficiency of engaging activities.

McGill’s memories still gnaw at her today. She described sleep deprivation due to extreme air conditioning, fluorescent lighting and lack of sufficiently warm clothing. She recalled the absence of any external stimulation: the lack of windows, the inability to see the sky and the deficiency of engaging activities.

The walls were all one color, usually beige or white. Steel cells, tables and beds were the only items in the lock-ups, unless a concrete slab protruded from the wall as a makeshift frame. Sleeping on the floor was not uncommon, nor was seeing the physically most vulnerable people being forced to sleep with their heads next to the toilet in an overcrowded cell. McGill remembered how inmates were talked at, not spoken to; and how the explicit use of her last name made her fail to feel like a human being, let alone like a child.

The United States leads the industrialized world in the number and percentage of children it locks up in juvenile detention facilities, according to Human Rights Watch.

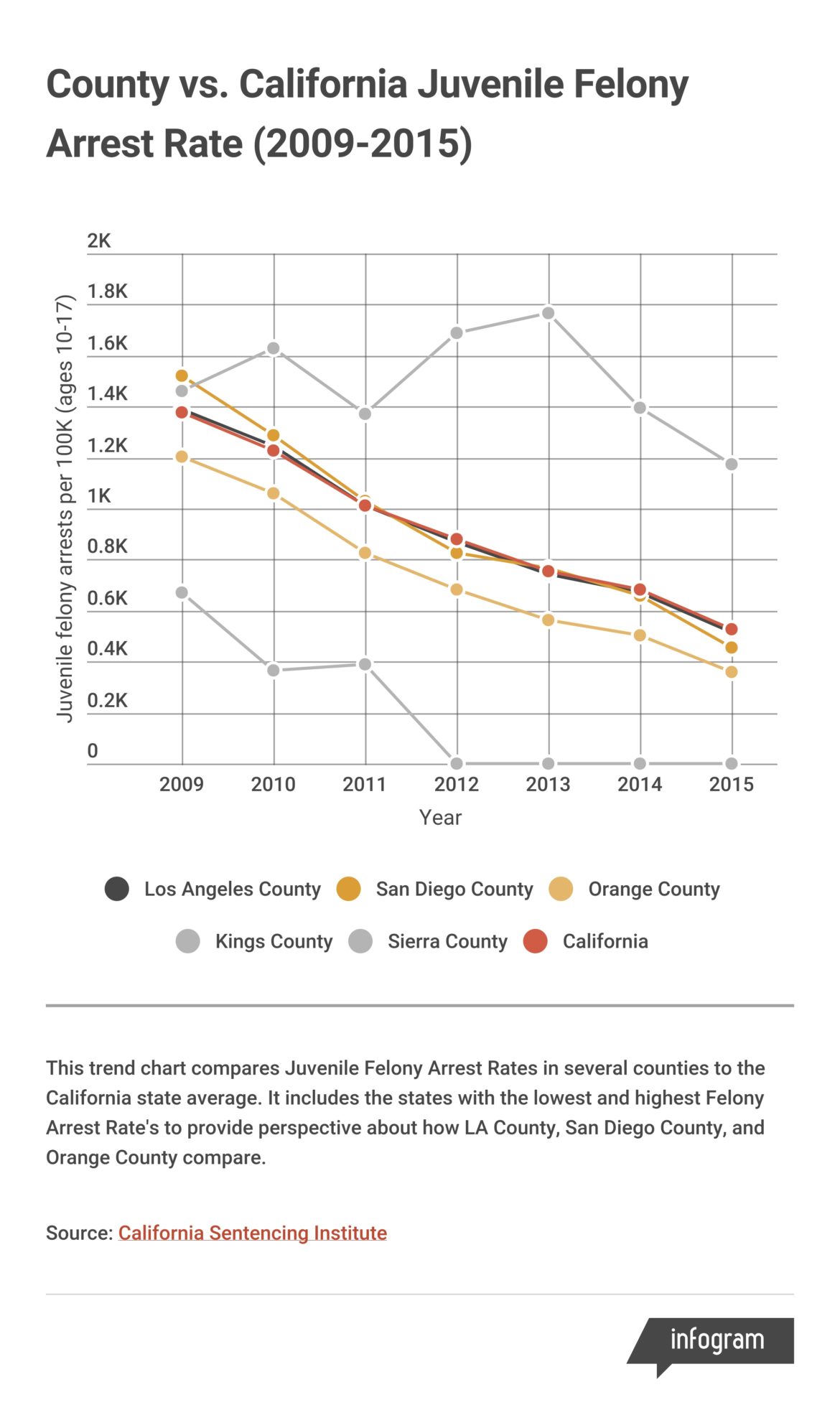

In California, 71,923 juveniles were arrested in 2015 according to a report from the California Department of Justice. Slightly more than 58,000 were referred to probation, about 13,000 were counseled and released, and approximately 1,000 youth were turned over to another agency.

Meanwhile, improvements have been made. Lawmakers unveiled a list of bills in March 2017 in an attempt to divert youth from a school-to-prison pipeline and keep them out of the juvenile justice system.

“We have made really big progress, we just have to do a lot more,” said Dr. Bo Kyung (Elizabeth) Kim, assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. “We still incarcerate the most vulnerable population in this country. ... More than any other country in the world.”

Confinement conditions

Among her bad memories were the powerlessness: “As a young person you’re in cells usually with no bathrooms. So, you’re pounding on the door or a plexiglass window ... in the door, to try to get someone’s attention so you could pee. [You are] especially desperate in the middle of the night when you’re locked in, and having people either know that you’re pounding and ignore you, or pretend not to hear you, and having to pee into a towel or into a corner or hold it all night. That was particularly horrible.”

But the boredom was the worst.

Being in a place where pencils, pens, books and paper are all considered contraband, she said, inmates could spend hours, days and sometimes months without the ability to read or write, let alone do anything else to stimulate your mind.

“Once I had a nickel on me that wasn't caught during the search and I wrote with it into an entire cell wall,” she remarked. Although there would be dayroom time, it was rarely programmed to help you grow.

Contemplating whether she had found solace in anything or anyone during her most vulnerable moments, she said, “[I] can't think of any positive thoughts that got me through anytime.”

Young people who go into the system are particularly vulnerable, McGill said.

“Because of your age or because of your lack of experience, you’re introduced to people who have been much more involved in the streets,” she said. “So, prisons, jails [and] juvenile halls are also breeding grounds for violence.”

McGill pauses for a moment before saying strip searches were obviously another distinct memory. She would have to “strip down naked in front of total strangers, not only the people that you’re locked up with but the guards. In [the] case of the youth system, it’s probation officers. In [the] case of the adult system, it’s usually sheriffs, sometimes police officers.”

The stench of the facilities is another feature she vividly recalls as being unbearable. “I think that anyone who’s been locked up can smell … exactly how it smelled when we were there,” she said. “And you can differentiate between the facilities you’ve been based on the smells they had.

“Sounds at night are also something that never leaves you,” McGill said, “whether it’s the pounding of doors, crying, screaming, people mumbling to themselves, people rhyming … yelling, arguing with each other.”

But even so, McGill said she was better off than many other people who have been in solitary confinement and were sentenced to life in prison.

Racial profiling

One of the most impactful things for her development was growing up in communities of color, she said.

“I think I had the benefit of seeing the obvious issues in the system from a very young age … When you’re white [like me], and you’re going through it, it’s really obvious to you that you’re getting preferential treatment.”

On the streets, McGill was treated as a victim while her friends were viewed as criminals. She recalled being taken aside by police twice and asked if she had been kidnapped. She was constantly queried about why she was in specific areas, if she knew they were dangerous and if she wanted a ride home.

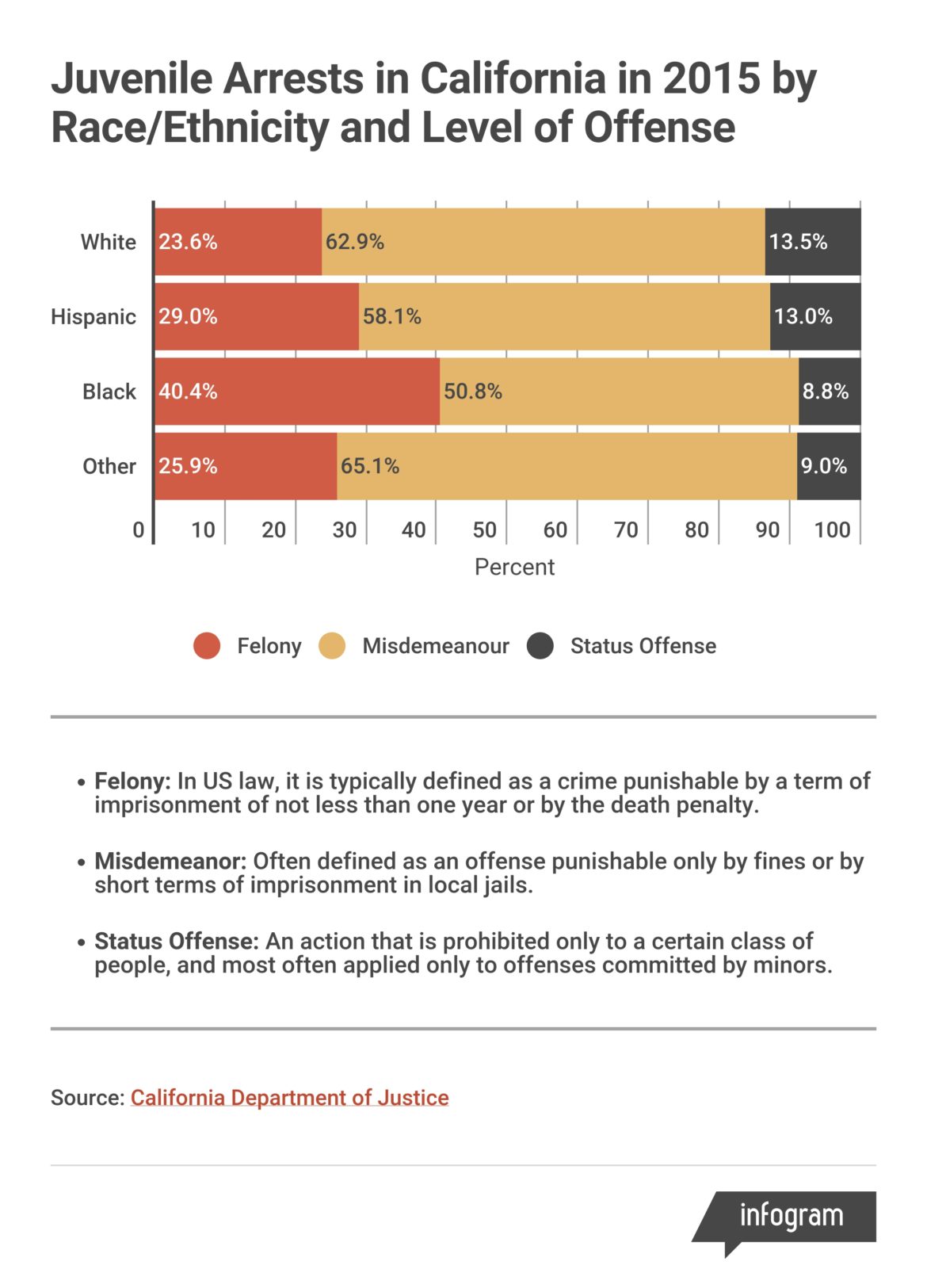

A 2017 report from Human Impact Partners found that in 2015, 88 percent of juveniles in California who were tried as adults were youth of color.

The record also cited evidence of “rampant racial inequities … in the way youth of color are disciplined in school, policed and arrested, detained, sentenced, and incarcerated.”

Crissel Rodriguez, the Southern California regional coordinator at the California Immigrant Youth Justice Alliance, agreed.

“We see that the zero tolerance policy has actually really affected communities of color,” Rodriguez said.

Kim said youth of color are much more likely to be in touch with police negatively at every single point of contact in the system, and they are more likely to be taken further into the system than out of it.

“The justification for that for the judges themselves, is that ... it’s dangerous, so we are going to detain them,” Kim said. “It’s a way to protect them. But under the purview of protecting them, they’ve further introduced them to a system that brings them back over and over again.”

Detention dispute

In 2012 Gov. Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 9, which supported judges reconsidering the sentences of juveniles punished to life in prison. After that, most of the state’s juvenile life-sentenced prisoners are being resentenced, according to The Sentencing Project.

Brown signed SB 394 in October, legislation that now outlaws the state from sentencing youth offenders to life in prison without possibility for parole.

Today McGill, 36, leads the Youth Justice Coalition, an organization that challenges the U.S. “addiction” to incarceration and race, gender and class discrimination in the juvenile “injustice” systems. To her, and most people in the coalition, this crusade is personal.

“The greatest feeling that myself, and I think other people, have got has come through our organizing and fighting back to change the system,” she said. “It’s healed us more than any other single thing has.”

Hello. The national Knight Foundation and the Democracy Fund like our work so much that they have agreed to match donations of up to $1,000 per person. They will spend up to $28,000 through the end of December.

So this would be an especially good time to donate to the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. Any money you give us up to $1,000 will be doubled.

Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

Thanks for listening.