Arkansas Nonprofit News Network

(This is one of four parts.)

In 2008, Wendy Jones’ teenage son, Corby, began getting into trouble with the law: skipping school, doing drugs, stealing. His behavior soon landed him in Benton County, Arkansas, juvenile court, followed by a stay in the local juvenile detention center, or JDC, a 36-bed, jail-like facility in Bentonville, not far from the home offices of Walmart.

Corby was just the sort of youth who might be expected to stop dabbling in illegal activity after a brush with the juvenile justice system. His mother had a good job with the city of Rogers, and, though she was raising Corby and his sister alone, she had a strong social network in her community. In theory, a night or two of detention at the JDC would have provided the jolt needed to make such a kid reassess his future.

But as with so many other teenage offenders, being locked up did little to alter Corby’s trajectory for the better. His drug use continued, and the court responded by clamping down harder, creating a cycle familiar to observers of the system.

“I had connections that most parents didn’t when I was going through the JDC with my son,” Jones said recently. “But as a parent, regardless of who you are, where you work, or who you know, it’s the most lonely, terrifying experience to go through with your child.”

“Basically, [JDC] was the only high school he went to, because he was in and out so much,” she recalled. “He went through all the counseling, all the rehab … really, anything that was offered.” Yet the court’s default response to Corby’s behavior was always yet another round of the juvenile equivalent of jail.

Jones describes herself as a “tough-love mom” who is “all for punishment” when necessary. But by the time her son aged out of the juvenile system in 2011, she had reached her own verdict about JDC detention, at least for Corby: “It was worthless. ”

“It was kind of at that point where it’s like, 'OK, this isn’t working,’” she said. “They’re still getting locked up over and over and over.” She pointed to statistics showing that the juvenile incarceration rate in the United States is the highest in the developed world. “That’s pathetic. … We shouldn’t have to keep building prisons for children.”

But then, around the time that Corby aged out, things began to change in Northwest Arkansas.

Juvenile detention rates dropped. Alternatives to incarceration expanded. In 2013, a national program called the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative began partnering with the court in Benton County and its counterpart in adjacent Washington County. Jones was asked to serve as the parent representative on the local JDAI board.

Kris Johnson

Wendy Jones

“They asked me because they really wanted the parents’ perspective, instead of it just being law enforcement, judges, prosecutors, defenders — you know, all the typical people involved,” she said. “When you’re talking about your child, and you’re in it, it’s completely different from being on the outside looking in. You’re living it, day to day.”

Jones served on the board for two years as the program got off the ground. Today, she said, she sees the county “actually working with kids. We’re not just locking them up. … I can’t say enough about the system and [Benton County Circuit] Judge [Tom] Smith right now. I truly believe in what they’re doing.”

Smith, who has been the county’s juvenile division judge since 2013, said his court uses confinement only “when we have to use it. We don’t use it just to use it. … The philosophy is lock up last, not lock up first.”

In 2009, 859 kids cycled through the Benton County JDC. In 2016, JDC intakes had decreased to 467, a 46 percent drop. Youths spent a total of 6,557 days detained at the JDC in 2009; in 2016, total detention days had declined to 2,844. Benton County’s JDC average daily population is now so low — it averaged between six and seven youths per day in 2017 — that a portion of the facility will soon be permanently converted into an emergency shelter.

Smith succinctly made the argument for reducing juvenile confinement: “It saves money, it saves resources, but more importantly, the data shows that once you start locking up a kid, the propensity to get locked up [again] increases tenfold. Once you start that process, their propensity is to be in the system longer.”

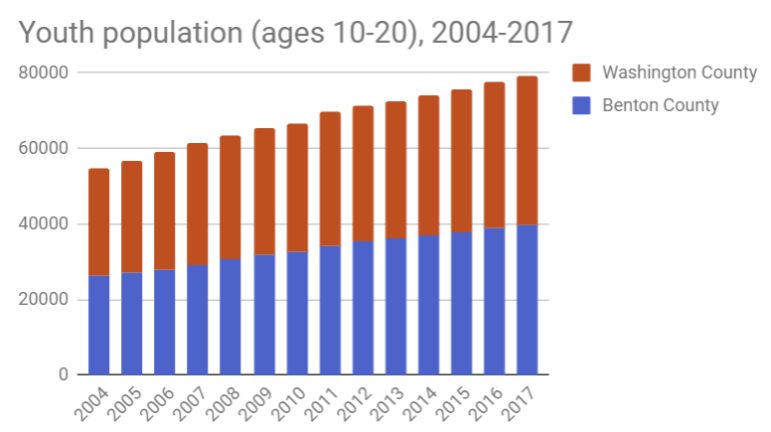

Locking up fewer kids hasn’t led to more juvenile crime. In fact, the number of delinquency petitions filed by the Benton County prosecutor dropped by 32 percent from 2009 to 2016. And at the same time that the JDC population was shrinking, the population of Benton County as a whole was rapidly expanding — it’s now the state’s second-largest county — meaning the per capita decrease in confinement has been even greater.

Similar trends have unfolded next door. In 2008, the Washington County JDC detained 915 kids over the course of the year; in 2016, intakes stood at 507. Like its neighbor to the north, the county’s general population has surged over the past 15 years as the economy has boomed in Northwest Arkansas.

Circuit Judge Stacey Zimmerman, who has presided over juvenile court in Washington County for 19 years, echoed Judge Smith on the hidden costs of excessive lockups. “The more entrenched they are in the juvenile justice system, the greater the chance they’re going to end up as an adult criminal,” she said. To that end, Zimmerman’s court has also embraced alternatives to detention, including a new evening reporting center that opened in April.

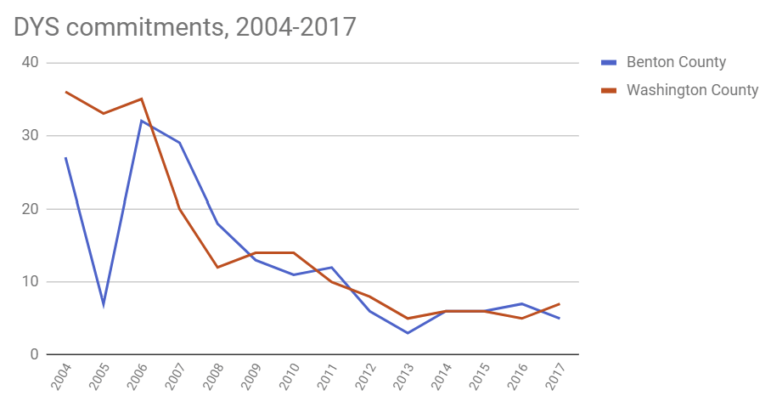

HIGHER POPULATION, REDUCED INCARCERATION: Despite rapid population growth over the last 12 years, Washington and Benton counties now send one-fourth as many kids to the DYS as they did a decade ago.

The changes in Northwest Arkansas are all the more striking when contrasted with the state as a whole. Other reform-minded jurisdictions in Arkansas have successfully reduced confinement in recent years — among them, juvenile courts in Pulaski and Faulkner counties — but the state overall continues to lock up large numbers of children.

There is little statewide data on the use of detention at county facilities, but a national census of residential facilities performed every two years by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention provides limited information. According to the OJJDP, there were about 99 kids held in the 14 JDCs across Arkansas on an average day in 2007. (In rural areas, a single JDC serves multiple counties.) In 2015, the most recent year that the OJJDP performed its snapshot, the one-day detention count for Arkansas had increased to 210.

Local juvenile detention centers are only half the youth incarceration picture. The juvenile justice system distinguishes between “detentions” at county-run JDCs and “commitments” to treatment facilities operated by the state Department of Human Services’ Division of Youth Services, which is intended to rehabilitate more serious offenders. Detentions are typically measured in periods of days or weeks; kids committed to the DYS by a judge’s order may remain confined for months or even years as they complete the terms of their treatment plan.

In Northwest Arkansas, the number of youths committed to the DYS plummeted over the last decade. In 2007, according to DYS data, Benton County committed 29 kids to state facilities. A decade later, in 2017, the number was five.

Washington County sent 35 kids to the DYS in 2006 — more commitments in a single year than the 29 made by the same juvenile court over the five-year period from 2013 to 2017. (The statewide DYS commitment rate also dropped from 2007 to 2017, but the percent decrease was just one-third as much as the decline in Washington and Benton counties over that period.)

“If a kid comes to DYS out of Benton County, we’ve exhausted all of our options. That’s just the way we view it,” Judge Smith said. He ticked off various alternatives to the DYS, including Youth Challenge — a program of the Arkansas National Guard — or vocational training through Job Corps.

Typically, Smith said, he will only commit a youth to the DYS who has committed rape or a violent crime involving a firearm. Even in some of those cases, he will first try inpatient psychiatric treatment at a facility such as Piney Ridge, in Fayetteville. “It’s when they refuse to get help … that we have to put them in DYS.”

Though such reforms stand out in Arkansas, what’s happening in Benton and Washington counties is consistent with national trends. The OJJDP’s census found 108,000 juvenile offenders locked up in the U.S. in 2000, a number that includes both detentions and commitments. In 2015, there were about 48,000. Arkansas is one of the few states in the nation that has failed to reduce confinement by double digits since the 1990s.

This reporting is courtesy of the Arkansas Nonprofit News Network, an independent, nonpartisan news project dedicated to producing journalism that matters to Arkansans. Find out more at arknews.org.