BATON ROUGE, Louisiana — More than 23 years ago, 15-year-old Damien Riley walked into the Legends Comics and Sports Cards store, browsed through the cards, then aimed his gun at the back of the head of 41-year-old store owner Michael Kleban, who was sitting at the counter listening to the radio.

Today Judge Richard Anderson in the 19th Judicial District Court in East Baton Rouge could revise Riley’s life sentence because of a series of decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court. Those rulings found that adolescents are less culpable because of their still-developing brains and ability to change.

In 2016 in Montgomery v. Louisiana, the most recent decision, justices ruled that Louisiana and other states must apply the court’s previous rulings about juveniles with mandatory life sentences retroactively, to prisoners like 71-year-old Henry Montgomery, who has spent a half-century at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola after being sentenced for murder at 17 in East Baton Rouge courts.

Inmates with life-without-parole sentences like Montgomery — and Riley — who had committed crimes as juveniles must now be given a “meaningful opportunity” to have their sentences reconsidered, the court ruled. That is no small task in Louisiana, which ranks third in the nation in the number of juveniles serving life, after Pennsylvania and Michigan.

In June, Judge Anderson changed Montgomery’s sentence to life with the possibility of parole. A parole hearing is tentatively scheduled for next month.

Riley killed Kleban with one shot in the back of the head that night in December 1994 and ran off with a wad of the store’s money before he was caught by police. He soon confessed to what he’d done and led detectives to the Stallard Arms Maverick pistol he’d thrown into a nearby canal called Bayou Fountain, telling them he’d paid $20 for the gun and a single bullet.

There was no question about guilt: Riley had murdered a beloved community merchant.

After listening to the evidence during Riley’s trial and hearing his taped confession, the jury was reluctant to put him away for life, even though it had voted 11 to 1 (Louisiana allows non-unanimous verdicts in certain criminal cases) to convict him.

“We all felt like this young man, the instant he did it, was like, ‘Oh my God. What have I done?’” jury forewoman Kellye Troth told local media at the time.

Jurors sent a note to Judge Curtis Calloway: “We, the jury, would like to ask that if it is in the judge’s power, (that) this young man be given any consideration allowed by the law during sentencing and offered any and all rehabilitation opportunities.”

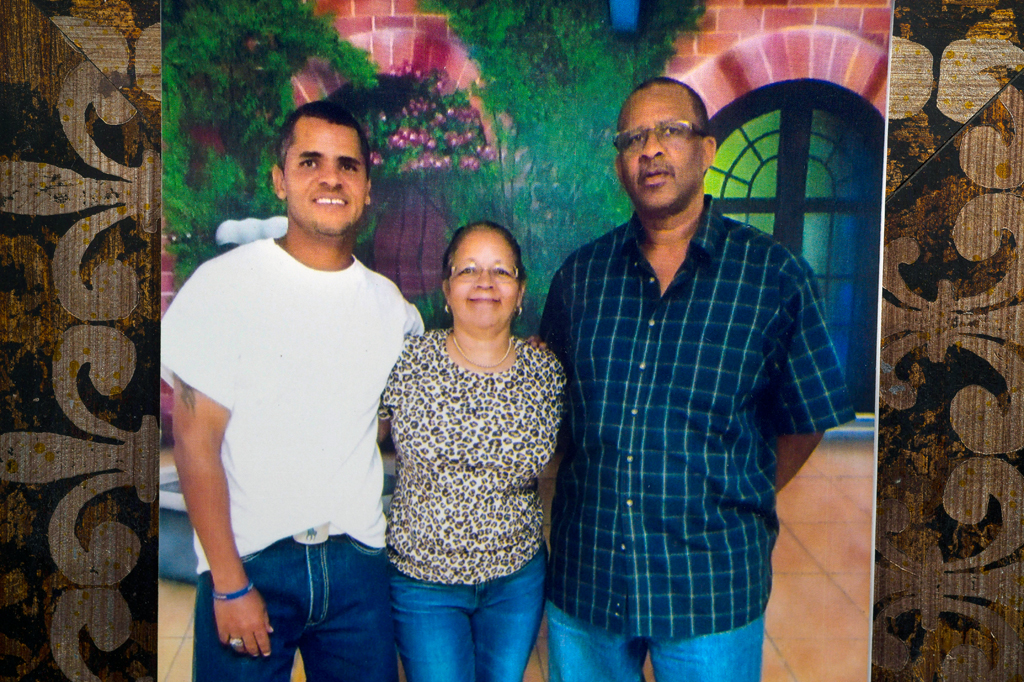

Travis Spradling/Baton Rouge Advocate

Damien Riley's mother Melvina Jones, right, and his stepfather Danny Jones, left, who's been a father to Damien since he was 4, in their dining room with a few photos of Riley, taken during their visits to Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

Judge’s memories

Details of that case and its defendant are still vivid in Calloway’s mind more than two decades later. “I don’t know why this kid stands out in my mind,” said Calloway, now 78 and retired. “This kid just seemed different. He was mild-mannered. He looked young and innocent. He looked like a little baby.”

Calloway, who has long volunteered with youth in his spare time, said he didn’t see a predator sitting at the defendant’s table. He saw an adolescent who “probably had no idea what he was doing.” He didn’t see Riley as incorrigible. “Who goes in to rob someone with a gun with one bullet?”

But Calloway’s hands were tied. Louisiana law required life without the possibility of parole for anyone convicted of second-degree murder. “I was obligated to follow the law,” he said.

Resentencing hearings like Louisiana’s have been criticized because they open old wounds for victims’ family members, who thought they had put the painful court process behind them for good.

Kleban’s nephew, Douglas Saltz, who was with his uncle at the store 20 minutes before the fatal shooting, said he understands the Supreme Court’s decision about adolescent brain function. “It makes sense,” he said. But he doesn’t believe it should apply to Riley. “I think three life sentences isn’t enough for him,” Saltz said.

Like other states, Louisiana allows juveniles with mandatory life-without-parole sentences a chance at a parole hearing after they’ve served a certain amount of time — in Louisiana’s case, 25 years. But Louisiana also created a district attorney safety valve that allows prosecutors to pursue life-without-parole sentences for certain selected defendants they considered the “worst of the worst.”

Even as a legislative committee hammered out the state law last year, Republican state Sen. Dan Claitor, a former district attorney himself, emphasized that the U.S. Supreme Court had directed that juvenile life sentences should be “rare” and uncommon. He issued a caution. “It will be up to the DAs from this point forward to follow the law,” he said. “You can’t declare everything the ‘worst of the worst.’”

Statewide, prosecutors ended up seeking life sentences for 84 of the state’s remaining 255 juveniles with life sentences, roughly one-third of the cases.

“That’s like sending an embossed invitation to the Supreme Court to tell us that we’ve done it wrong yet again,” said Katherine Mattes, director of the Tulane University Law School’s Criminal Litigation Clinic.

Katy Reckdahl

Melvina Jones looks at a number of photos of her son Damien Riley, who is serving time at Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola after being convicted of murder 20 years ago.

No funding for hearings

The legislature allocated no prosecution or defense funding for resentencing hearings, which makes the cases a heavy lift for defense attorneys, said lawyer Ben Cohen, who represents two defendants who received life sentences as teens. To do it right requires juggling everyday details on a tight budget while also getting to the core of your task as a lawyer, he said.

“This is a human endeavor filled with the challenges of finding paper for the copier and at the same time figuring out what makes a person unique,” Cohen said, referring to the U.S. Supreme Court mandate that each defendant receive an “individualized” hearing.

To provide the sort of personalized investigation and interpretation that the Supreme Court decision requires would run $58,000 for the defense per hearing, said James Dixon, head of the Louisiana Public Defender Board, who calls the hearings “an unfunded mandate.”

In a few courts, judges have awarded mitigation money, to hire specialists who typically get copies of key records and conduct extensive interviews with crucial people.

Not in Riley’s case. Mummi Ibrahim, of New Orleans firm Ibrahim and Associates, who is representing Riley pro bono, requested money for a mitigation expert during the hearing but was turned down by Judge Anderson, she said. So she handled the case solo.

That’s a near-impossible task, Dixon said. “Let’s say I did this investigation. I can’t call myself to the stand,” he said. “You’re probably also going to have to have expert testimony beyond the mitigation specialist, including psychologists and psychiatrists, people to testify about that child. All of this is necessary but expensive.”

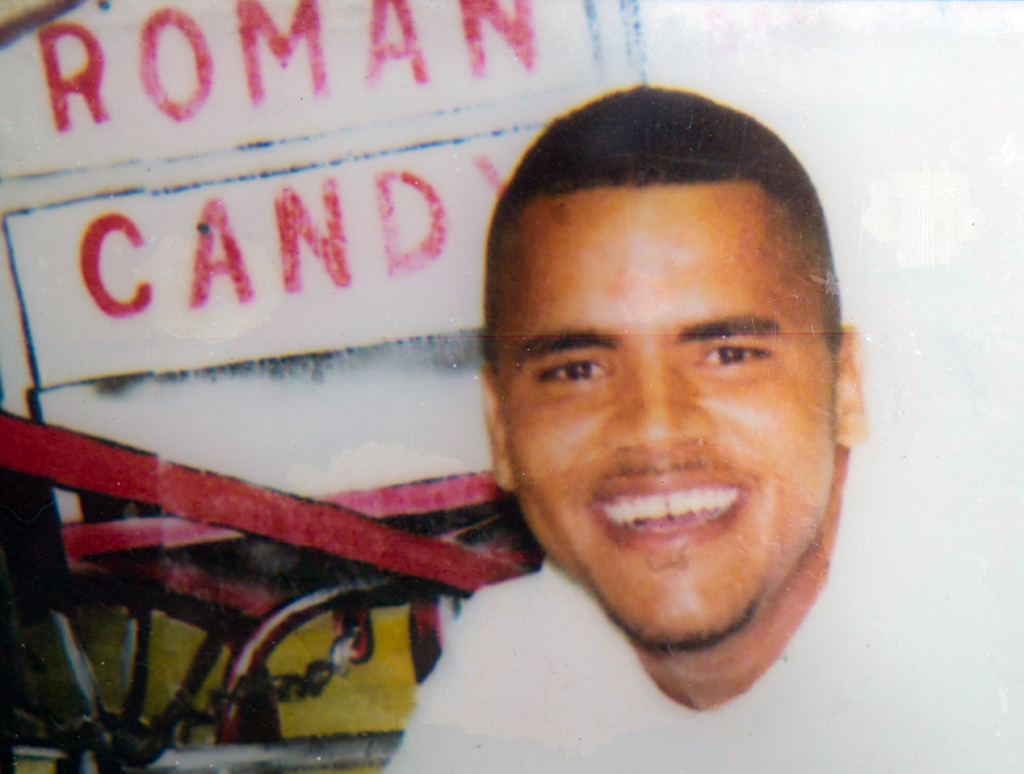

Travis Spradling/Baton Rouge Advocate

Damien Riley in a photo taken during a family visit at Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

Death penalty protocols

For adults, the worst legal punishment possible is the death penalty. Since the Supreme Court barred juveniles from being given the death penalty, the highest criminal penalty for children is life without parole.

So when the U.S. Supreme Court instructs lawyers to supply juveniles with “individualized hearings,” death penalty lawyers already know what that means, because that’s the same term used in death penalty law. It means mitigation specialists, investigators, experts and psychiatrists, all interpreting their client’s life for a judge and a jury.

It took years of cases and appeals and court decisions to crystallize the role of mitigation in death penalty cases.

Juvenile-mitigation specialists don’t have to forge a new path. For years, a group of core mitigation people working on death penalty cases developed protocols that should be followed.

“So the issue with juvenile life-without-parole cases isn’t that there’s not a formula to follow,” said Chris Murell, a longtime death penalty defense attorney who is representing juveniles currently serving life sentences.

Murell, executive director of the nonprofit Promise of Justice Initiative, also represents juveniles in current cases where prosecutors are seeking life-without-parole sentences. This is still possible going forward in Louisiana as long as the defendant receives a two-part proceeding, a trial and a subsequent mitigation hearing that’s similar to the penalty phase part of a death penalty case.

“My approach with juvenile life-without-parole cases is that I do the same kind of social history and interviewing techniques that I do in capital cases,” he said. “But I don’t have the resources.”

Lawyers who have worked in death penalty law have seen more than 40 years of death penalty litigation on these very same issues. “Where we’re at with these juvenile-life cases now is where we were in 1993 when I started practicing in Louisiana, doing death-penalty work,” said lawyer Carol Kolinchak, who consults on juvenile-life issues and provides training to lawyers working on these cases in Louisiana.

All through the 1990s, Kolinchak said, death penalty lawyers were filing motions for funding. “We were appealing cases where, at the penalty phase, an attorney merely put a client on the stand to say, ‘I’m sorry,’ and a mother on the stand to say, ‘Don’t kill my child’ and that was a wrap.”

Similarly, Murell often hears about defense lawyers who are doing very little for mitigation for new cases of juveniles who face life sentences: They simply argue for 15 minutes or put a mother on the stand.

“The standards are not being followed, literally not in a single case,” he said. “How people will be represented will entirely be dependent on what parish [county] they’re in.”

Death penalty lawyers also fought for years to prove that they needed to pay certain experts and mitigation to mount a constitutional defense. They won that battle. Now those charged with defending people with juvenile life sentences may follow the same process.

Tim Mueller/Baton Rouge Advocate

In a 1994 file photo, Baton Rouge police detectives (from left) Chris Pickett, Frank Wolfanger and crime scene investigator Cosmo Giglio pull a handgun from Bayou Fountain used by Damien Riley in the murder of Michael Kleban.

‘Unfunded mandate’

For Kolinchak, what’s happening now is very familiar: “The Supreme Court is giving us an unfunded mandate and the legislature created a process, but no funding. Then the DAs made overbroad decisions to charge. Now individuals are going to individual courts who are saying no to the funding. It’s exactly the same thing we’ve seen before.”

The Juvenile Law Center (JLC) in Philadelphia, like the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights (LCCR) in New Orleans, has been carefully tracking statewide results of resentenced juveniles with life sentences.

“What we’re seeing so far is that lawyers, judges and prosecutors are all trying to get the lay of the land, to understand how to deal with these cases,” said Jill Pasquarella, supervising attorney for LCCR.

Brooke McCarthy, an Equal Justice Works Fellow, is helping coordinate hearings and data in Pennsylvania, which has the nation’s highest number of juveniles serving life sentences. So far, McCarthy said, they’ve found that funding varies widely by county and judge.

In Philadelphia County, which has the most cases, defenders get an initial $3,500 to start. “They’re being very frugal,” she said, noting that they are being careful to create better records for appeal and trying to educate judges about basic child development.

JLC lawyers are also already penning briefs about obvious issues: What threshold must be met to receive life without parole? How do you prove that someone is “irreparably corrupt” and thus one of the “rare” and “uncommon” juveniles for whom life sentences are appropriate?

To date, well over half of Louisiana cases that have gone to hearings have ended up with a new life-without-parole sentence, Dixon said. That tells him that the hearings haven’t carried enough information to tell the defendant’s story.

“I think the writing is on the wall — you’re going to need a mitigation specialist,” Dixon said. “If a judge denies, that will go up on appeal and come back. I see this as being very expensive, drawn out. We’re going to have litigation for years on this stuff.”

Travis Spradling/Baton Rouge Advocate

Damien Riley, left, his mother Melvina Jones, center, and his stepfather Danny Jones in a photo taken during a visit they made to Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

‘Not all peaches and cream’

District Attorney Hillar Moore is pursuing life without parole in Riley’s case partly because of the heinous nature of the crime.

Also, according to Moore, Riley’s upbringing shouldn’t have created a murderer. “It is without question that Damien Riley’s family members love and support him, just as they have his entire life,” Moore wrote in a memorandum filed after the hearing in October. “This factor alone distinguishes from the vast majority of individuals involved in the criminal-justice system.”

That the district attorney summarized Riley’s life in that idyllic way is a signal that moments of Riley’s life were overlooked. “It was not all peaches and cream,” said his mother, Melvina Jones. “I’m not a psychiatrist but there was lots going on.”

Just last week, Jones got a call from her sister about an old Christmas card she’d found. “We didn’t have long-distance calling then, so I had written her to say that I had put Damien in the boys’ home.” Only then did Jones remember how she and her husband, Danny Jones, had brought Riley to a place for wayward teens after he talked back to her in a way she did not like.

He stayed there about four weeks, she said, but she had not thought about it for years and certainly had not mentioned it to Ibrahim so that they could secure records for the hearing — which might have been important, since it was not long before the shooting, she said.

Jones talks to her son nearly every day. And sure enough, a few hours after lunch on a recent afternoon, he called.

He agreed that his stay at the boys’ home was about a month. “I remember wondering, ‘Why did they send me here?’ he told her. “I really felt like I was being pushed away.”

Sitting in court in October, he’d seen Kleban’s sister and felt overwhelmed with shame. “I wanted to tell her how sorry I was. I wanted to ask for her forgiveness,” he said.

More than anything, he hates that he ever owned a gun. A few years before the shooting, the family had moved from the small town of St. Gabriel, Louisiana, to an apartment in a rough part of Baton Rouge. He saw a young man killed. Then one day, a man in a car had pointed a gun at him and his younger sister when they were walking to the corner store. “It was scary,” he recalled. “I wanted to be able to protect her. To protect myself.”

He didn’t tell his parents about the man in the car. But he bought the pistol.

At that time, he really didn’t feel safe at home, he said as his mother talked to him on speakerphone. In response, his mother slumped in her chair. She and his stepfather had gotten in a bad cycle, where they were drinking too much and fighting, in a way that sometimes turned violent, she said.

That fateful night, he had taken the bus to a friend’s house, hoping to stay over, away from the drinking and the fussing. He stopped at a Winn Dixie supermarket to call his friend from the payphone. No answer. So he walked to Kleban’s store. He remembered looking at sports cards of John Elway and Steve Atwater of the Denver Broncos.

Then, as he leaned over to look more closely at a card, the gun in his pocket tapped against the store’s glass case. He’d forgotten he had it, he said. But knowing he had the gun, he acted, in a way that he will never quite understand.

At home, things changed rapidly once her son was arrested, Jones said. “After the shooting, we figured out that it was everything — the bad neighborhood we were living in, how we were living, all of it. So we moved and we changed to save the other two kids.”

“If only we’d done it earlier,” Jones said. “Maybe we could have saved all three.”

This story is also being published by the Baton Rouge Advocate.

This story has been updated.

I know this story all so well. We we’re kids and he has always been my friend.It would be at his best interest to give him and his mother a chance at freedom.

The case has been made for every child but the innocent child my name is Jerome Skee Smith in 1985 at the age of 15 I was convicted of first degree murder. Prison in Louisiana it’s about punishment and retribution not reform and Rehabilitation.

Pingback: Louisiana Man With Life Sentence Gets Chance to Be Paroled | Youth Today