A chilling email was leaked the day before Louisiana officials announced they would not file criminal charges against two white Baton Rouge police officers in the shooting death of Alton Sterling outside a convenience store in July 2016.

According to published reports, a police special operations unit was being deployed from another part of the state, its troops told to pack eight days-worth of clothing. Extra security plans were being implemented and equipment was being moved in to fortify the city. Police headquarters was surrounded with barricades. The state’s attorney general’s office took the extraordinary step of telling its employees not to report to work the day the decision would be announced.

At best, the widely-talked about preparations were an overreaction. At worst, they were an indication that once again, the city of Baton Rouge was willing to go to war against its residents.

After the state’s announcement last week that no charges would be filed, an uneasy calm filled the city. A few days later, when Baton Rouge Police Chief Murphy Paul announced the firing of officer Blane Salamoni and the three-day suspension of officer Howie Lake II, the city remained calm.

Activists say it’s not for lack of outrage.

Local Courage

Rosalyn Scott, a Baton Rouge resident arrested while protesting last year, said the decision to leak the information may have been done strategically as a scare-tactic. In July 2017, Scott was protesting the slow pace of the Sterling investigation when she said she was thrown to the ground, had a police officer’s foot shoved in her face and felt his gun shoved in her back.

“Intimidation is a real thing,” said Scott, who was charged with entry and remaining after forbidden and resisting an officer.

I reported from Baton Rouge in the days immediately following the shooting, talking with young people among the hundreds who protested the killing of the 37-year-old father of five.

Over several days, nearly 200 people were arrested — including myself and at least three other reporters. Many were terrorized by volatile and seemingly out-of-control police clad in riot gear, driving armored vehicles and brandishing weapons of war.

Journalists and peaceful protesters — including one protester choked by police while holding a simple sign saying “Love” — were treated like enemy combatants.

Officers marched toward us in lock-step, batons beating on shields while commanders barked orders and slapped each other on the back, some directing the attack from the porch of a nearby house.

We were blasted repeatedly with an LRAD, a disorienting and deafening sonic weapon originally used to deter attacks on naval vessels, developed after the bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen.

We were chased down at gunpoint, tackled, cuffed and dragged through yards and parking lots, pulled down the street by officers, some shouting inaudible commands from behind gas masks — all for exercising our First Amendment rights to peacefully assemble, or in my case to document that assembly.

Yet like those arrested for peacefully protesting that day, I was charged with resisting an officer.

Humiliated

Since then, not a day — not one single day — has gone by that I don’t think about the brutality of what happened in Baton Rouge in July 2016 and later that night as we were crammed, 24 to a cell, into the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison, after being tear gassed, strip searched and humiliated.

I think about it every time I cover a protest. Or cross paths with a police officer. Or feel someone coming up behind me. Or hear certain high-pitched sounds. Or sirens. Or running feet.

But as terrifying as it was, it wasn’t even close to what Sterling must have felt as he took his last breath that night in front of the Triple S Food Mart.

Shortly before announcing Salamoni’s firing and Long’s suspension, Baton Rouge Police Chief Murphy Paul said actions of law enforcement need to reflect the legal and community standards, as well as the practices and policies of the department and he had a message for the community.

"Treat our police officers with the respect that their positions deserve, and I assure you that the men and women of the Baton Rouge Police Department will reciprocate that gesture," said Paul.

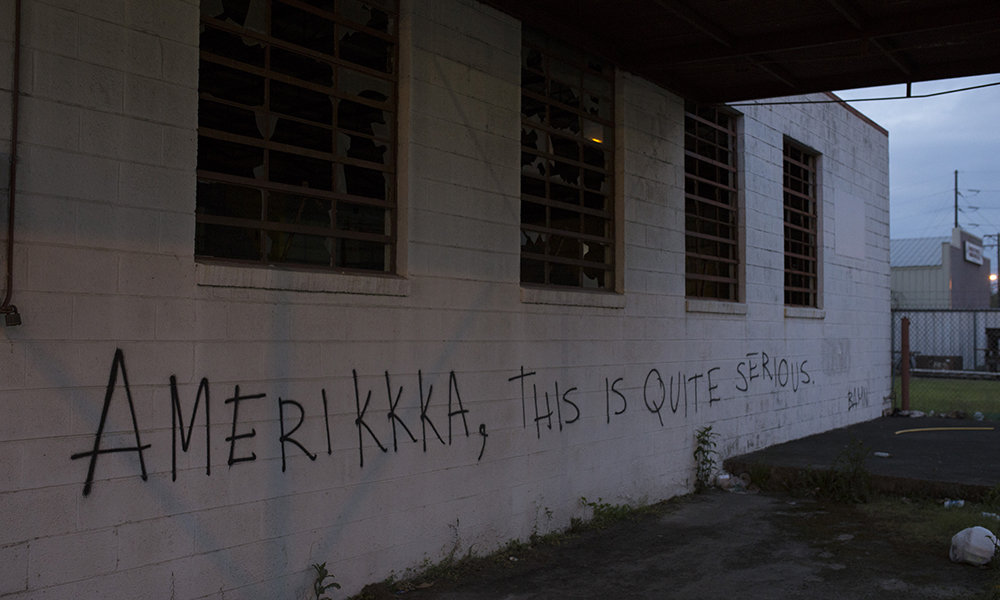

Graffiti on an abandoned building across the street from the Triple S Food Mart in Baton Rouge.

“Listen to my words very carefully,” said Paul at the Good Friday afternoon press conference. “Please stop resisting. Stop running. When a police officer gives you direction, listen. Follow his directives.”

Graphic video shows the treatment Sterling received from Salamoni and Long.

“What I did?” asked Sterling as he was confronted by the officers.

“I’m saying what I did?”

“Don’t fucking move or I’ll shoot your fucking ass, bitch,” barked Salamoni. “Put your fucking hands on the car. Put your hands on the car I’m gonna shoot you in your fucking head, you understand me?”

“Hold on man,” said Sterling, his hands now on the hood of the car.

“Don’t you fucking move, I’m gonna shoot you in your fucking head, you hear me? Don’t you fucking move,” said Salamoni.

Seconds later, Sterling was tackled, tased, shot six times in the chest and left to die in the parking lot, officers cursing him as he bled to death on the ground.

Sterling didn’t resist. He didn’t run. He attempted to follow directions. Video shows Sterling did exactly what Paul is now suggesting he should have done.

And he’s still dead.

Eyes of the World on Baton Rouge

In the days after Sterling’s death, the eyes of the world were focused on Baton Rouge and police had the opportunity to show the world they could interact with the community in a respectful way. They did the opposite.

What I saw made me wonder how many more Baton Rouge residents have been subjected to police brutality. I wonder how many have gone unreported and uninvestigated.

I was targeted by the police because I had a camera, not because of the color of my skin, an unearned and undeserved privilege given to me as a white woman by a society steeped in white supremacy and built on the backs of brown and black folks.

The more than half of the residents of Baton Rouge who aren’t white aren’t afforded that privilege. Alton Sterling certainly didn’t have it. Neither did Eric Harris or Victor White or Dejuan Guillory or Calvin Toney, all men of color, all killed in recent years by Louisiana police.

To my knowledge, there’s been no research done on — what by all indications are — the detrimental mental health impacts on Baton Rouge residents by the police killing of Alton Sterling and the brutally militarized treatment of protesters that followed. There needs to be.

A study released in 2016 found stress levels in Ferguson, Missouri — where protesters decrying the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown were met with a similarly militarized police response — to be significant, with black participants exceeding clinical cutoffs for PTSD and depression more than white participants.

“When things like this happen, it’s a bit of a brutal reminder to the young people that ‘no, we are still considered second class citizens, we are still viewed with these horrible stereotypes and we can’t get justice or protection from law enforcement,”said Monnica Williams, an associate professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences at the University of Connecticut and Director of the Laboratory for Culture and Mental Health Disparities.

It’s not surprising that information like the kind leaked Monday could cause hesitation among would-be protesters.

“If it’s a community that has a history of violence or abuse, it can be seen as a threat or warning or intimidation,” said Williams.

Karen Savage

Baton Rouge, July 2016

After the Media is Gone

While my experience was horrifying, I don’t live in Baton Rouge. I went to cover a story and though I often cover stories in Louisiana, I was released from the prison the day after I was arrested and went home.

Long after the media was gone, Baton Rouge residents of all races were left to pick up the pieces, to try to heal, a challenge to say the least. Only a week after the protests, a gunman shot six Baton Rouge police officers, killing three.

Though the gunman denounced the protesters online prior to the killings, some in law enforcement and elsewhere wrongly accused organizers affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement of instigating the shooter. In May of last year, federal officials announced they would not charge Long or Salamoni, who fired the shots that killed Sterling, with federal civil rights violations.

Days later, community members calling for police reform and accountability say their First Amendment rights were violated when they were thrown out of a Metro Council meeting after speaking out about Sterling’s death.

In November, police shot and killed 24-year-old Calvin Toney in The Palms, a North Baton Rouge apartment complex. That killing is still under investigation.

And now, nearly two years later and the only ones who’ve been arrested in relation to the killing of Alton Sterling have been those who put their own lives on the line trying to persuade authorities to arrest Sterling’s killers.

Once again, police prepared for war against the people of Baton Rouge and even with a new mayor — who called for the firing of the officers and who publicly stated she supports her citizens’ First Amendment right to peacefully protest — neither Salamoni nor Long will face even one day behind bars for Sterling’s death.

Shortly after Paul’s announcement, the police union issued a statement supporting both officers and Salamoni’s attorney has vowed to appeal his firing.

“For a lot of kids of color, it’s very disheartening, it’s disillusioning, it erodes your sense of safety and security because law enforcement is supposed to be there to protect you when something bad happens, but when you see not only are they not there to protect me, they’re there to hurt me, the world looks very dangerous,” said Williams, who has conducted research on the relationship between law enforcement and Black communities.

She said changing that perception could take years.

“People have built up their distrust over decades, you can’t just pretend it’s not there and start anew,” said Williams.

Last year, on the one-year anniversary of Sterling’s death, Scott and a few dozen protesters approached the police headquarters looking for answers and transparency into the investigation.

She said police put up barricades and told them to leave. Scott remembers telling officers that if police headquarters is a private building then they are all mercenaries.

Moments later police opened the barricades and attacked her and other protesters.

Who, she asked, would want to come out and protest after seeing that?

“This place, this whole place,” said Scott, sweeping her arms. “They have never stopped with the prejudice. It’s like we’re returning to the old days. We’re having to fight our freedom all over again. After all of the successes of the civil rights movement we are fighting for our rights fighting for justice, all over again.”

Hey Karen. This is Rafiq. Again, a great piece. Again, I commend you on your objective coverage and personal courage.

Thanks, Rafiq!