NEW YORK — The program is short: two counseling sessions, two hours each. But for teens and adults who have been arrested for the first time, it can save them from a lifetime with a criminal record.

Project Reset is a diversion program that was started in 2015 by the Manhattan District Attorney's office as an opportunity for teens who have committed nonviolent crimes like trespassing and turnstile-jumping to stay out of criminal court by completing alternative programming.

Amy, 16, stands in the middle of a large contemporary art gallery in Harlem, talking to some of her peers from the program. The space is open and bright: Natural light streams into a welcoming lobby and white walls highlight a glossy photo exhibition to her left.

Amy is one of hundreds of 16- and 17-year-olds in Manhattan who opted to do some of their Project Reset hours at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, a gallery that pairs teens in the program with artists. The artists lead group activities for the kids, teaching them about positive self-expression.

Amy is one of hundreds of 16- and 17-year-olds in Manhattan who opted to do some of their Project Reset hours at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, a gallery that pairs teens in the program with artists. The artists lead group activities for the kids, teaching them about positive self-expression.

“I had never really thought about art, so that was amazing,” Amy said.

Though the program is short, it provides a distinct change of pace for the teens. For several of Amy’s peers, all arrested for low-level misdemeanors as she was, this was the first time they had ever been in a contemporary art gallery.

“Half the kids I was interacting with didn’t get to do art ever,” said Marquita Flowers, one of the artists in the program.

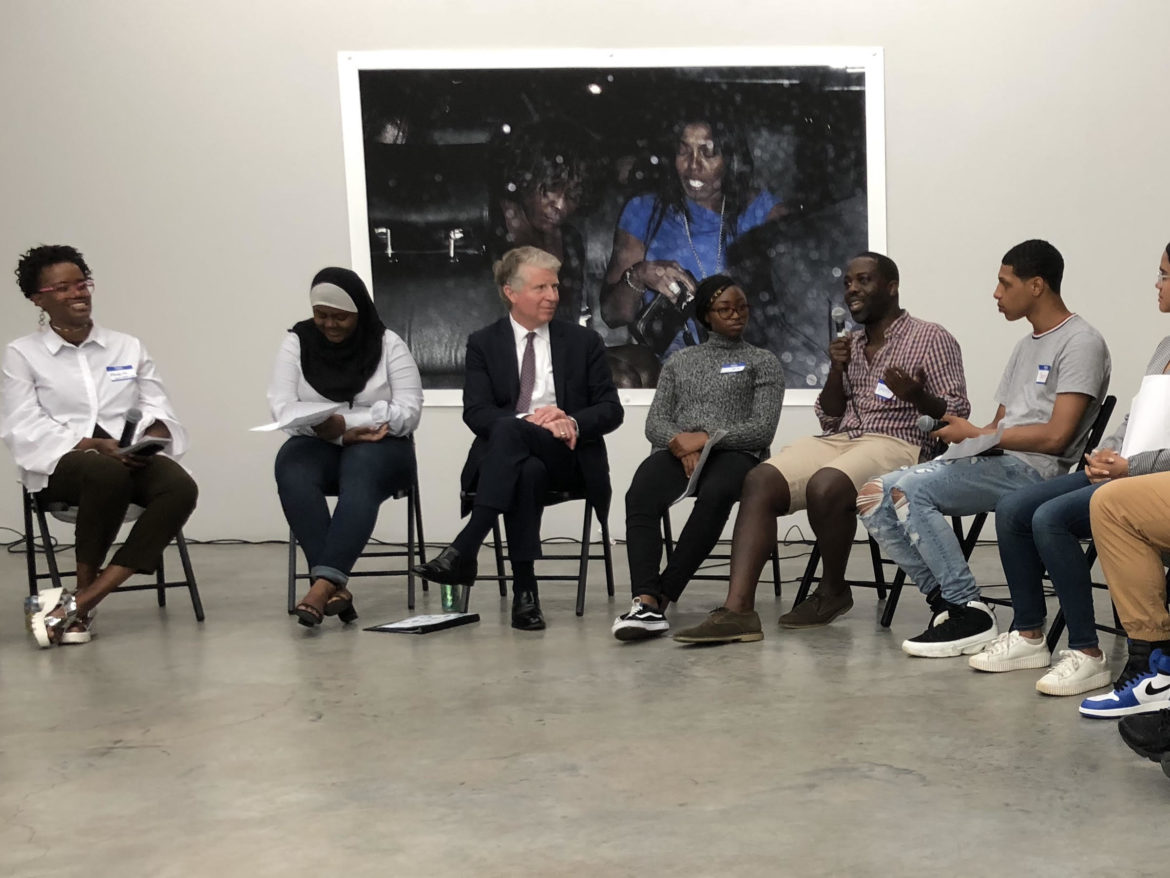

On Wednesday night, Flowers joined other artists and alumni from Project Reset to talk with District Attorney Cyrus Vance about the program’s future.

Low-level offenses

Derek Fordjour, who came to Project Reset as an artist a little over a year ago, says the vast majority of teens he works with in the program fit a very specific profile. He described a kid hanging out with his or her friends and getting involved in youthful indiscretions. Maybe they were loitering in an abandoned building or maybe they were pressured to jump a turnstile.

Instead of turning that indiscretion into a criminal label, the program offers its participants a second chance. “It’s prevented me from having a record, and from having something I did that was so little ruin my life and chances of having a job,” Amy said.

Fordjour says this is a more humane response to low-level crime enforcement. “I think those kids need a conversation. I don’t think they need to wear cuffs, and to be processed, and for their families to be taxed — they’re already very often low-income families,” he said. The program “saves so much societal trauma. And individual trauma.”

Since its inception, Project Reset has had a high completion rate: 919 teens in Manhattan and Brooklyn have participated since March 2015, with 98 percent completing their hours, according to program analysis from the Center for Court Innovation.

Last February, the program expanded to adults in certain precincts, with 192 participants so far and a 100 percent completion rate. Starting this July, Project Reset will be available to all adults in Manhattan.

How it works

The process begins at the point of arrest and before arraignment, when a police officer alerts potential participants that they may qualify for diversion programming. If participants complete the program, charges are dropped and they do not have to appear in criminal court.

Funding comes from asset forfeiture, which is then reinvested in Project Reset.

It still isn’t clear how many first-time offenders who are eligible for the program are opting in. Flowers noted that communicating the nature of the program has been an issue in the past. Some officers, she said, have described the program as a “bootcamp,” intimidating potential participants.

Despite the program’s success, the Wednesday event also underscored the large racial disparity that exists in the city’s enforcement of nonviolent crimes.

At one point Fordjour turned to a group of Project Reset alumni and asked how many of them felt they could have been let off with a warning. All of them raised their hands.

One alumnus, Jose, turned to District Attorney Vance. “If you look at this room you will notice that we are mostly brown and black people,” he said. “What does that say about enforcement and prosecution in New York City today?”

Vance responded: “We have a justice system that is focused on arresting black and brown people. And it’s not designed to be racist, but, in practice, it is obviously racially skewed.”

This story has been updated.

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.