The order came from a 15-year-old on a bicycle near a Chicago park in 2001: “Shoot him, shoot him.”

Benard McKinley, 16, obliged. And Abdo Serna-Ibarra, 23, never made his way to the soccer field.

McKinley was later arrested and charged as an adult with first-degree murder for the killing of Serna-Ibarra. In 2004, Cook County jurors found him guilty.

The sentencing judge, Kenneth J. Wadas, went on to make an example of McKinley and his murder, condemning the young man to 100 years in the Illinois Department of Corrections — 50 years for the murder and a consecutive 50 years for the fatal use of a firearm. The sentence was necessary to deter other criminals, Wadas said in court, and would enable others to play soccer with “one less Benard McKinley out there with a handgun blowing them away."

With no chance of parole or early release, McKinley was doomed to either live to celebrate and surpass his 116th birthday, or grow old and die within the fortress of the state’s prison system.

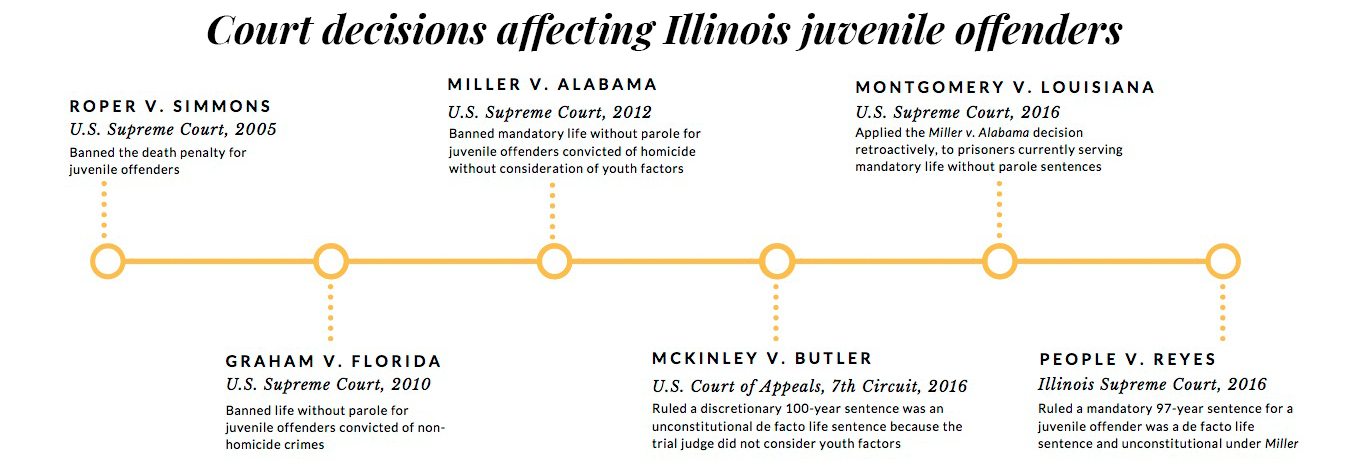

A court reckoning

Over the past two decades, scientific researchers and courts began grappling with a question that could dramatically shift the course of McKinley’s life: When it comes to crime, are children and adults different?

Courts across the country slowly began to address the issue, bolstered by research showing that the human brain, particularly parts responsible for controlling impulses and assessing consequences, is not fully developed until one’s early 20s. And so courts ushered in a new era of decision-making, ruling again and again that children accused and convicted of crimes must be treated differently than adults.

The decisions culminated in Miller v. Alabama, a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that laws declaring mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, even for those convicted of murder, are unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. In the opinion, authored by Justice Elena Kagan, the court found that the mandatory sentences precluded judges from considering the defendant’s “chronological age and its hallmark features — among them, immaturity, impetuosity and failure to appreciate risks and consequences.” The Court reasoned that the youngest offenders have “diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform,” and to require those mandatory sentences without considering features of youth constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

Jeanne Kuang

.

That ruling applies to anyone under the age of 18, and was made retroactive in 2016 after another Supreme Court ruling, Montgomery v. Alabama. “What is with this magical moment?” asked former Cook County Circuit Court Judge Daniel M. Locallo, now a defense attorney. “You’re 17 and 364 days, the day before your 18 birthday, allegedly your brain isn’t developed enough.” But one day later, he mused, “it is?”

With the new standard set, a wave of prisoners across the country with mandatory life sentences, including some 80 inmates in Illinois, have or are in the process of receiving sentences that take their youth into consideration.

Abby Blachman

Benard McKinley

But McKinley is not among them.

Though Wadas imposed a 100-year sentence, to be served in its entirety, the judge was not mandated to sentence McKinley to spend his life in prison; in fact, he was only required under Illinois law to issue a minimum punishment of 45 years in prison.

After his conviction was upheld in the Illinois appellate courts, McKinley turned to the federal courts contending that his sentence was not constitutional.

In March 2014, U.S. District Judge John J. Tharp Jr. refused to strike down the sentence, reasoning that a judge’s imposition of consecutive 50-year sentences, while possibly amounting to a life sentence, was not based on a mandatory sentencing scheme that the Supreme Court prohibited in Miller:

“Whether McKinley’s sentence should have been lower due to his age is not for this Court to say; the Illinois courts held that the sentence was not excessive, and that conclusion is not in conflict with the federal Constitution,” Tharp wrote.

Those left behind

In Illinois, it is rare for juveniles who did not receive automatic life prison terms to win new chances at sentencing, leaving most of those with long sentences to languish in prison for decades, an Injustice Watch review found.

A review of custody data from the Illinois Department of Corrections revealed that, as of last December, at least 167 current inmates were arrested for crimes as juveniles and are set to serve 50 years or more in prison without parole eligibility, leaving them likely to die in custody but not eligible for resentencing under the dictates of Miller. (It is not possible to know the exact number of young offenders serving long sentences at the Illinois Department of Corrections because the agency does not specifically keep track of that information.)

The imposition of long sentences is especially harsh in Illinois, a state that does not afford parole to most prisoners and that requires offenders convicted of murder to serve 100 percent of their punishment, with no chance of early release based on factors like good conduct or rehabilitation. Such sentences almost certainly lead these inmates to either spend the rest of their lives incarcerated or be released with precious little life left.

Research indicates that incarceration has a jarring effect on life expectancy. In studying a group of inmates released from New York state correctional facilities over a 10-year period, Vanderbilt University Professor Evelyn Patterson found that the former prisoners could expect to shave two years from their average life expectancy for every one year of incarceration. Furthermore, Patterson found, undoing the negative effect on longevity takes time. It took former inmates two-thirds of the time spent in custody back on the outside to recover from the harm of incarceration on life expectancy.

The United States Sentencing Commission considers a 39-year prison sentence the equivalent of life.

Because Illinois almost entirely abolished parole in 1978, these juvenile offenders do not get the same chance to show rehabilitation and change that they might get in other states. About a third of states do not currently employ the traditional practice of parole for newly convicted inmates, according to a report published by the University of Minnesota’s Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, but Illinois is one of three states nationwide that stopped utilizing parole four decades ago, making it nearly nonexistent for the current prison population.

The approximately 80 juvenile offenders in Illinois who became eligible to have their sentences reconsidered all were convicted of killing more than one person — Illinois law mandates life for anyone convicted of multiple murders. By contrast, Illinois state appellate judges have mostly declined to find that the cases of other violent youthful offenders, like McKinley, fall under the protections outlined in Miller.

There is no national legal standard on how many years is too many for a juvenile to serve. Courts across the country have differed on the issue, creating varied standards on what length of a prison term can legally be considered a life sentence.

“Getting rid of formal life without parole was the tip of the iceberg,” said Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel for the Pennsylvania-based Juvenile Law Center, which has advocated for lesser sentences for juveniles convicted of crimes.

Across the country, about a dozen states have passed laws requiring that young defendants sentenced to long prison terms get a chance at parole. Legislators in Illinois have proposed a bill that would give periodic parole opportunities to newly convicted young offenders; so far those efforts have stalled.

Injustice Watch interviewed 11 Illinois inmates serving prison sentences of 50 years or longer for crimes they committed before they were 18. They spoke about their childhoods, often marred by poverty and violence; their hopes of one day re-entering the outside world; and their sense that, despite the growth and progress they said they have made entering adulthood in prison, society has already thrown them away.

Death by another name

Andrew Anderson and Ramirez Taylor both grew up in south suburban Cook County with childhoods marked by death, addiction and drugs.

As young teens they became friends. But as they grew older, the blocks between where each grew up, and the gang alliances associated with them, turned the pair into rivals. “He became the enemy because someone made him the enemy,” Taylor said. Anderson said the gang rivalries that bound them both were so powerful that the childhood friends could have marked the other for death had they encountered each other on the streets.

After their friendship fractured, both were accused of committing separate murders before entering adulthood. They were charged and detained simultaneously in the Cook County Jail.

Anderson was arrested first, for the February 2006 shooting of 25-year-old Troy Pickett, a man he first met when he was 11 years old, selling candy bars and drinks with a friend at a housing project. Pickett told the boys they had hustle, Anderson said. The older gang member would go on to recruit Anderson into the Gangster Disciples, and train the boy to sell crack cocaine.

But by the time he turned 17, Anderson said he began distancing himself from his mentor, weary of the daily drumbeat of shootings and murders around him, and afraid he could soon be the next victim.

A month shy of Anderson’s 18th birthday, Pickett drove up to Anderson and a friend who were standing near a friend’s home in Robbins, Illinois, and told them to get in the car for a drug pickup. They climbed in. As they drove, Anderson said he saw Pickett reach for his gun. Anderson recalled what Pickett — a “real killer” whom Anderson said he once saw pointing a gun at a young girl — was capable of, and said he feared for his life. He reached for his own gun, and shot Pickett.

Five months after Anderson was booked into the jail on murder charges, 17-year-old Taylor was brought in on charges of unlawfully possessing a firearm while wearing a bulletproof vest as he fled from police.

Police sent the gun in for forensic testing, and connected it with the unsolved August 2006 shooting death of Shone Matthews in Riverdale, Illinois, during a game of dice. Taylor admitted in a videotaped statement to police that he was present during the killing, but said he was unaware of the plan beforehand and that he fired his weapon into the dirt, not at Matthews. Police found ammunition cartridges from two different firearms at the scene.

Taylor was charged with Matthews’s murder; no other suspects were charged in that case.

In jail, Taylor said a fight almost erupted between his allies and Anderson’s. But, Taylor said, the fight never happened, and instead the two former friends hashed out their differences.

“If it wasn’t for jail, I don’t think we’d ever be able to come eye to eye,” Taylor said.

In jail, Anderson said he tried to take his education seriously and earned his GED. After seven years — his entire adult life — behind bars, he went to trial. He claimed self-defense, but jurors were unconvinced, finding him guilty of first-degree murder. The judge sentenced Anderson to 60 years in custody.

“To me, that meant the death penalty, like you gotta die in prison,” Anderson said. “No matter what you do, you can’t change and if you do change, we don't care. Just go die in prison.”

Taylor was tried and convicted separately of both the weapons charge and the murder, and was sentenced to serve a combined 68 years in prison.

“They socked it to him, as far as they could jam it,” said Judith Taylor, his grandmother.

Both Anderson and Ramirez Taylor are now incarcerated at the Menard Correctional Center in southern Illinois, where they said they talk regularly about what led them to be enemies and the older gang members who took advantage of their ignorance. They offer their renewed friendship as proof that teenagers, once easily manipulated, can mature.

Anderson said he is asking to be transferred to a different state prison to access college courses. He said he refuses to dwell on the fact that he could die in prison, focusing instead on being a role model for his younger siblings. He said he wants to one day help youths at risk of choosing life on the streets.

“I grew up in prison … I learned to think 20, 30 years down the line,” he said, adding, “That’s something I didn’t see when I was living on the streets.”

In the ensuing 12 years since Taylor was arrested, both his aunt, who raised him following his mother’s death, and his grandmother said they have seen change in their relative.

The sentence has weighed heavily on Taylor, now 29. “I feel like a dead man walking,” he said in one telephone interview from Menard.

Different state, different rules

Inmates like Taylor and Anderson face a complex web of legal rulings as they try to ask the courts to reconsider their sentences in light of their youth.

Following the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Miller, a judge must order a new hearing upon finding that a juvenile offender’s prison term amounts to a life sentence, and that the sentence was ordered without consideration of the defendant’s “age and the wealth of characteristics and circumstances attendant to it.”

In May 2016, an Illinois appeals court rejected Taylor’s request for a new sentence, acknowledging the consequential length of his 60-year term for the murder conviction, but finding his trial judge had exercised appropriate discretion after noting his age and difficult childhood during sentencing. Anderson’s resentencing request has yet to be heard by a Cook County court.

Nationwide, courts have created a patchwork of legal standards regarding juvenile sentences. Rulings by judges across the country show stark differences in the lengths of prison sentences that are upheld for youthful offenders.

In neighboring Iowa, for example, the state supreme court in 2013 threw out a sentence that made a juvenile offender parole-eligible only after serving 52½ years because it afforded him only “the prospect of geriatric release” without a meaningful opportunity to demonstrate rehabilitation. Citing that decision, the Wyoming Supreme Court in 2014 ruled the same way on a sentence that required a juvenile offender to serve 45 years before having a chance at parole.

“The challenge that all these courts are facing is literally where to draw the line and how to pick a number,” Levick said.

The Ohio Supreme Court so far has only drawn the line at a 112-year sentence; in Minnesota, the state supreme court has declined to draw the line for an aggregate sentence that included parole eligibility after 90 years.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2012 Miller decision banning mandatory juvenile life without parole was narrow, said Perry Moriearty, a law professor at the University of Minnesota who has represented juvenile offenders seeking shorter sentences in that state.

The decision “doesn’t say what is an alternative sentence, and left open for interpretation lots of questions,” Moriearty said. “Do we accept disunity [among states]? Should we be consistent when it comes to interpretation of the Eighth Amendment?”

“These kids will languish” in prison without more explicit national legal standards on lengthy sentences, she added.

The parole possibility

In Illinois, one solution advocates are pushing to help this group of offenders is bringing back parole.

Under current state law, the only juvenile offenders with parole opportunities are the aging handful who were convicted before 1978, when the state’s sentencing laws drastically changed. That year, the state’s criminal justice system shifted from sentencing convicted criminals to a range of years with the chance to ask for early release through parole to applying fixed sentences to all inmates. A later law, enacted in the 1990s, curtailed the ability for offenders convicted of violent crimes to shorten their prison sentences through good behavior and eliminated the opportunity altogether for those convicted of murder.

A 2017 bill filed in the Illinois legislature would have given newly convicted inmates who committed crimes before the age of 21 the periodic chance to ask for parole, after first serving 10 years for lesser crimes and 20 years for first-degree murder or aggravated sexual assault. The bill sat in a House committee, never called. The bill was refiled this year and passed a Senate committee last month.

Advocates like Levick and Moriearty point to California law as one solution to long sentences: It requires all young offenders to be eligible for parole after serving 15 years of their sentences for lighter crimes and 25 years for homicides. After a minimum of 15 years, advocates say youths’ brains are developed enough with age for a “second look” to see if they have sufficiently changed in prison, or for parole boards to set goals for rehabilitation if they have not.

Jeanne Kuang

Based on laws passed after the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miller v. Alabama, these are sentences juvenile offenders convicted of serious crimes such as homicides must serve in the listed states before being eligible for parole or a sentence reduction. (Some of these states still allow harsher sentences for juveniles, for the gravest offenses.)

At least 13 other states and Washington, D.C. have passed similar laws, giving young offenders a chance to ask for parole release or a sentence reduction after first serving as few as 12 and as many as 35 years in prison, depending on the state and severity of the crime.

Such measures are not without opponents. Before voting against the prior version of the Illinois bill last May, Republican state Sen. Michael Connelly suggested that 10 years was too short a term for violent offenders to serve before having “an opportunity to be back on the street.”

“We need to start thinking about the people who are victims of these crimes and the families of the victims and the neighborhoods that these crime victim families live in,” Connelly said.

Illinois victims’ rights advocate Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins said frequent parole reviews would force victims to relive the traumatizing memories of their loved ones’ death, which she said is more painful the more often the memories come up again, and akin to “torturing the victim.”

Bishop-Jenkins, who began advocating for crime victims after her sister, brother-in-law and their unborn child were murdered in their home by a 16-year-old boy in Winnetka in 1990, said she supports greater consideration of a defendant’s age and mental health at sentencing, and more programming in prisons for rehabilitation. But she said victims should not be subjected to the prospect of an offender’s release unless the inmate is a good candidate for parole, and said she believes one “mid-sentence review” is appropriate for those who are rehabilitated.

“If you’ve got a big sentence, and the purpose [of a parole opportunity] is to show they’ve changed, all you need is one” chance, she said. “It’s the cost versus benefits. Every five or 10 years makes it so that the victims’ family members can never get away from it.”

Another opponent, Republican Sen. Chapin Rose, raised concerns that an unelected parole board could undo a prison sentence set by state lawmakers.

Matt Jones, associate director of the Office of Illinois State’s Attorney Appellate Prosecutor, said the age of 18 is a “pretty bright line” for extending parole eligibility.

“We think that accepting that premise creates some serious questions or concerns,” Jones said. “If they have diminished culpability … what does that mean for their ability to join the military, or get married or choose to have an abortion.”

Prosecutors statewide are divided on allowing parole opportunities for offenders under 18, he said.

While Cook County State’s Attorney Kimberly M. Foxx supports the current bill, in April state’s attorneys in seven counties surrounding Cook County signed a letter to all 118 Illinois House representatives strongly opposing it, arguing the bill would lead to an increase in violent crime.

“It is naïve to suggest that allowing violent offenders to be released from prison early will do anything other than increase violent crime committed by juveniles,” the letter, issued by DuPage County State’s Attorney Robert B. Berlin, reads. “The General Assembly should be looking at ways to incapacitate violent offenders instead of letting them out early.”

This March, a group of inmates at the Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, Illinois, who are students in a class held a mock debate about the best way to reintroduce parole in the state. It was attended by state legislators and public officials.

Benard McKinley, convicted of shooting Serna-Ibarra on his way to a soccer game, was one member of the debate class. He described at the event the “emotional numbness” he felt as a young adult facing a 100-year sentence. Soft-spoken and bespectacled, he said he’s tried to better himself in prison, participating in a letter-writing program and completing paralegal training. In two days, he would start taking a DePaul University course in the hopes of one day getting a bachelor’s degree and attending law school.

He made a plea to legislators to allow inmates like him to get a chance at parole.

“There are other stories out there that are better than mine,” he said.

Tides turning in Illinois

After Judge Tharp turned down McKinley’s petition, the inmate appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, where his attorneys argued that during sentencing the judge had barely acknowledged his young age, and ignored the rehabilitative strides McKinley made in jail, including obtaining his GED, and enrolling and excelling in classes.

Less than a year later, by a 2-1 vote, McKinley became one of the rare lucky ones.

His case was sent back to the trial court to review his sentence. Now-retired appellate Circuit Judge Richard A. Posner authored the opinion, writing that the trial judge “should have considered whether, in a situation of excitement, McKinley had the maturity to consider whether to obey his confederate’s order, or was prevented by the circumstances from making a rational decision about whether to obey.”

Instead, Posner wrote, the judge “treated McKinley as if he were not 16 but 26 and as such obviously deserving of effectively a life sentence.” The decision deemed McKinley’s sentence, though discretionary, still in need of another look.

Attorneys for McKinley and prosecutors came to a joint agreement to carry out a new sentencing hearing for the 33-year-old, one that would consider his young age and developing brain at the time he pulled the trigger. Judge Wadas has not yet issued a ruling vacating McKinley’s sentence.

Exoneration Project attorney Karl Leonard, who is one of the lawyers representing McKinley, said the legal team is now gathering mitigating evidence and preparing to bring in an expert witness in the hopes of getting McKinley a lower sentence.

Leonard said he hopes to be able to reach an agreement with the state on a sentence, but does not yet know what amount of years that would be. As to whether Leonard thinks McKinley would fare well if parole was brought back for young people like his client, he said he did not know.

“I think the better solution is just to not be sending children away to prison for the rest of their lives,” he said.

This article was written by and originally ran in Injustice Watch.