Access to courses is the first step toward meaningful educational opportunity for students who are removed from their homes and communities and placed in secure facilities. Under federal and state laws, students attending schools in juvenile justice facilities are entitled to educational opportunities comparable to those they would have if they were attending their neighborhood high schools.

Bellwether Education Partners

Hailly T.N. Korman

Now, a first-of-its-kind review of the available data reveals substantial gaps in such opportunity at juvenile justice schools across the country, particularly in math, science and credit recovery.

Depriving vulnerable young people of the types of classes they would otherwise have access to is punitive and short-sighted. Equitable education programs in juvenile justice schools are not just required by state and federal law, they are proven to reduce recidivism, to improve life outcomes and to increase the well-being of communities.

But our new analysis confirms what was long suspected: States across the country are not meeting their obligations to provide equitable education opportunities to the students in their care.

One key finding of our analysis is that students attending juvenile justice schools have less access to credit recovery opportunities than their peers in neighborhood schools. Credit recovery programs allow students to retake courses they previously failed and do so on an abbreviated timeline so they can earn those credits necessary to get back on track to graduation. This lack of access is especially troubling given ample historical and anecdotal knowledge that the majority of students in juvenile justice facilities have been disengaged from school and are likely to be achieving far below their grade level with many gaps in their transcripts.

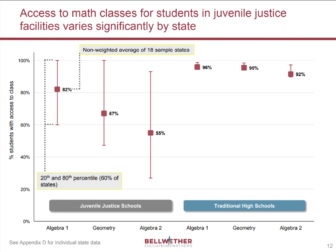

Students attending juvenile justice schools across the country also have less access to rigorous high school level academic coursework. For example, they have less access to math courses than students in neighborhood schools, and that gap grows as students progress through the typical math pipeline of Algebra 1 - Geometry - Algebra 2.

There are a number of plausible, innocent explanations for this disparity. For example, students in juvenile justice facilities may be grouped in multilevel math classes that are recorded as Algebra 1 or a school’s assessment of the most common student needs may lead them to believe that no students would be prepared to engage with higher-level math content. Regardless of the justification, the fact remains that students in juvenile justice schools have consistently less access to rigorous math content than their peers.

Pass rates lower

And even among those students who take Algebra 1, their achievement is consistently lower than that of their peers attending neighborhood schools, with an average Algebra 1 pass rate of 61 percent, as compared to 95 percent pass rates in traditional high schools. There is also much larger variance in pass rates than there is for traditional high schools.

The difference in pass rates could have a number of explanations, all of which may be true: It is possible that students are less prepared to be successful, that instruction ranges in quality and that the standards for passing are not as uniform. But for students, the effect is the same. Having limited access to math coursework and not passing those courses they do take sets them up for later school failure when they return to their communities.

Juvenile justice facilities, like their adult prison counterparts, are notoriously opaque institutions. Their schools are not subject to the same kind of scrutiny that we take for granted in our neighborhood schools. The complexity of their governance structures make it difficult for anyone to build a good analysis of the effectiveness of any of their programs. In the words of the Southern Education Foundation in their 2014 report “Just Learning,” juvenile justice schools have been, for decades, “off-the-books enterprises.”

While the data points are limited and we cannot comprehensively describe every program at every school or in every state, the gaps that we identify in this report accumulate to make clear that states are failing to serve their students who are attending school while incarcerated in juvenile facilities. We hope that this new information helps to support advocates, policymakers and system leaders who are driving changes to states’ juvenile justice practices in order to improve the life chances of young people who are being held in secure facilities.

Hailly T.N. Korman is a principal at Bellwether Education Partners, a national nonprofit with extensive experience in the fields of correctional education and justice-involved youth.

Pingback: Friday News Roundup: July 13, 2018 – Justice Programs Office