NEW YORK — At Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center in Brooklyn, barbed wire and tall unclimbable fences enclose the housing building, basketball courts and outdoor areas, like in every jail or prison. Detention hardware and security cameras are all over the place, like in every jail or prison.

Yet, says the facility director, Louis L. Watts, Crossroads is anything but a jail or a prison.

“When parents come, they see the outside and they tell me, ‘Oh my god, my son is in jail,’ but when they come inside and see, they say, ‘Wow, I could sleep here!’ They see that here their kids are taken care of,” Watts said.

“When parents come, they see the outside and they tell me, ‘Oh my god, my son is in jail,’ but when they come inside and see, they say, ‘Wow, I could sleep here!’ They see that here their kids are taken care of,” Watts said.

As part of a campaign to highlight the role of the city Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) in the implementation of raise the age, legislation raising the age of criminal responsibility to 18, city officials gave news media a rare tour of the facility, offering an insight into what New York’s juvenile corrections will look like in the future.

The state will now divert young offenders away from prisons and jails where they’ve been sent for decades and to alternative-to-detention facilities like Crossroads. Youth under 18 will now be processed through Family Court rather than the criminal courts, offering them a better chance to turn their life around.

“Juveniles should be treated as juveniles. Young people should be treated as young people,” said David Hansell, ACS commissioner, during the tour of the center. "We in New York are on the cusp of one of the most far-reaching and progressive reforms in juvenile justice in decades and that’s raise the age.”

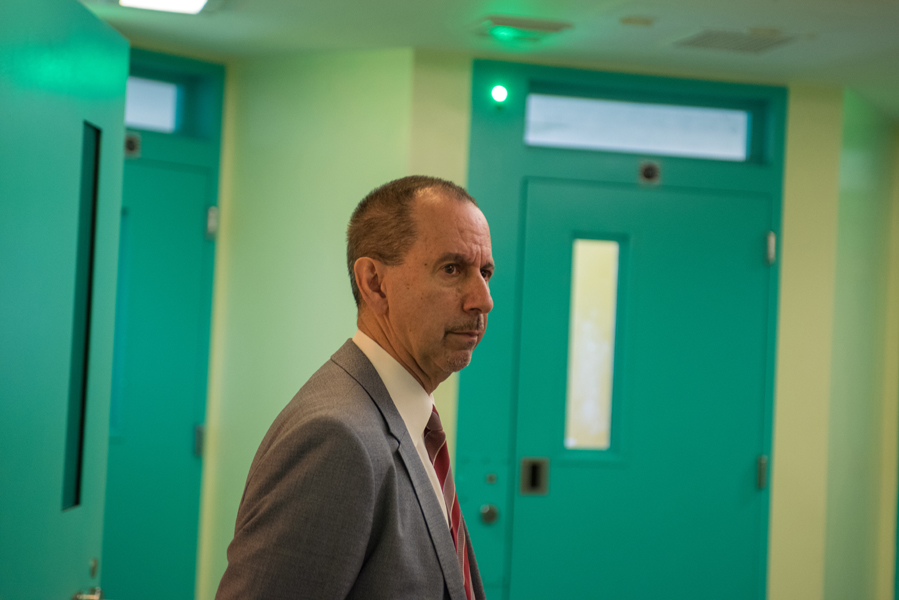

Louis L. Watts, the executive director of Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center, tells reporters about improvements made to the facility.

Thousands could be affected

The law goes into effect on Oct. 1, when children under 17 will no longer be confined in county jails. One year later, the same law will include 18-year-olds too.

State government estimates indicate that an average of 28,000 16- and 17-year-olds are arrested in New York every year and could be potentially be affected. Of those sentenced to detention, 80 percent are black or Latino, demographics reflected in Crossroads’ resident population.

At first glance, Crossroads, at the border of the Brownsville and East New York neighborhoods, looks like many other imposing, foreboding jails for juveniles around the country. But a walkthrough is enough to suggest a different possibility — that of a place where young offenders are given a chance to build on the time they’re forced to spend away from the home, while still being able to be what they are: children.

Bright colors overpower the concrete grey. A wide backyard is filled with blue tables, green chairs and yellow awnings. A blue-orange metal jungle gym provokes a city park feeling.

Signs of young minds at work are everywhere: painted murals in the hallways; drawings and hand-written posters on classroom walls; even a small vegetable garden and live chickens the young residents help tend to.

There are no grey jumpsuits like those worn by inmates at Rikers Island or at the prisons. Instead, kids wear T-shirts, sweat shorts and sneakers, just like they would on a regular summer day at a basketball court near home.

At first sight, Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center looks like a prison. Tall, unclimbable fences and barbed wire suggest the idea of confinement. But the facility has been remodeled based on a new approach to juvenile correction to make it feel less like a place to do time in and more like a place to learn, administrators say.

Activities and book discussions

An education program dubbed “Freedom School” keeps them busy for most of the day. They also learn how to cook and do manual work in specially designed classrooms and labs.

“G-O-O-D M-O-R-N-I-N-G,” a group of youth spelled out. “Good morning! Wake up! Good morning!” they chanted, as the commissioner walked into their classroom.

Students discussed the books they read in the summer. A male student talked about “Born a Crime,” by South African comedian Trevor Noah, “The Daily Show” host.

“This book is called ‘Born a Crime’ because basically white people and black people, they couldn’t engage, they couldn’t have babies,” he said. “Excuse my language,” he continued. “They couldn’t have sex with each other. It was illegal for a white person and a black person to have a baby with each other.”

The teens shared their takes on “I Got a Job,” a book they read recently, which tells the little-known story of the 4,000 black elementary, middle, and high school students who voluntarily went to jail in Birmingham, Ala., between May 2 and May 11, 1963.

“The book was about segregation, about what happened to our ancestors and stuff, about how white people and black people couldn’t be together, and go to the same schools and stuff,” another male teenager said.

Another student recalled a day in recent weeks when, after reading excerpts from the book, the youths continued their class in the backyard, marching, chanting and holding signs they made “to honor people from before who used to fight for their freedom.”

The material covered in class seeks to empower youths and teach them to fight for their freedom, taking inspiration from the civil rights movement, officials said.

Cell inside Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center in Brooklyn.

Missouri model

Crossroads embraces a correctional approach made popular by the state of Missouri, which began decades ago to rehabilitate children through programs that employ highly trained staff and emphasizes therapy and rehabilitation over punishment. The Missouri alternative-to-detention facilities are also smaller than prisons and don’t look like prisons.

Studies have found that less than 8 percent of youth held at such facilities reenter the justice system after release.

Staffers at Crossroads go through a six-week intensive training split between time spent with youths and classroom sessions, where they learn about trauma and mental health. They are taught how to talk to children and get them to express how they feel.

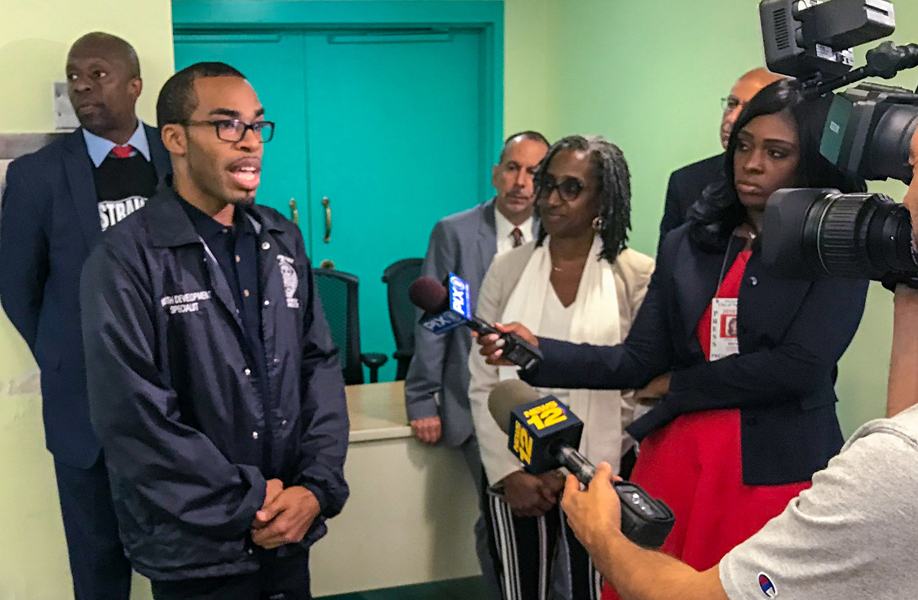

“We’re actually able to deal with the youth, to able to speak to them, to know de-escalation skills, different things that we’re equipped” with now,” said Jorel Holland, a youth development specialist at the center.

“Instead of the conflict getting bigger, we’re able to sit down each time we see that conflict arise, and have a conversation amongst each other,” he said.

Raise the age, which was signed into law in April 2017, diverts 16- and 17-year-old defendants to Family Court or to judges who are specially trained to deal with children.

Far from being a milestone of progressive policy, raising the age of criminal responsibility to 18 was a long-due fix to a backward justice system that for decades had prosecuted young offenders as adults, according to reformers and advocates. New York was among the last two states in the country to do so; North Carolina raised the age for only nonviolent offenses to 18.

Commissioner for the Administration of Children’s Services David Hansell visits the housing unit of Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center, an alternative-to-detention facility in Brooklyn. An administrator of the center said the youths in custody spend “very little” time in their cells and most of it engaging in rehabilitative activities.

Some incidents

Since it opened on Aug. 1, 1998, the center has had some success, but also numerous incidents that stained its reputation and eroded community trust in the agency that runs it.

In October 2015, a center employee was arrested for allegedly throwing a chair at a 15-year-old after a physical encounter. The staffer was then suspended. Another employee was arrested for shoving and punching a youth in the head. Neither incident was reported in the news.

Sometimes the employees were victims of violence. Some former Crossroads staffers have said they found themselves in difficult situations when the youths were the assailants but they couldn’t use force to defend themselves.

Denunciations of mismanagement and violence have cast doubt on the staff’s ability to handle at-risk youths who have experienced violence and trauma before entering.

But Watts, the center director, and ACS representatives have always deflected criticism, insisting detention centers like Crossroads are safe, pointing to self-reported statistics suggesting a significant decrease of incidents in recent years.

“Safety in our facilities is a top priority, and we have worked hard to create a system of care within our secure juvenile detention system that is grounded in best practice and designed to promote a safe, secure environment for youth and staff,“ Hansell said in a statement.

According to the self-reported numbers, incidents requiring the restraint of youths in custody went from 560 during the fiscal year 2015 down to 407 in 2016, then down to 237 in 2017 and is now at 206 for the current fiscal year. Child abuse allegations have also decreased from 41 in the fiscal year 2015 down to 34 in 2016 and to 16 in 2017.

During the tour of the facility, administrators and staffers were outspoken about their efforts to make the Crossroads a safe place for young offenders where they can learn from their experiences and get ready to find their freedom in society once they’re out.

One male teenager, grateful not to be in prison, had words of hope and determination.

“Coming here told me ‘I don’t want to be away from home’ and that I don’t want to come to this facility or a worse facility. I don’t want to come back to none of that,” the boy said, sitting in a classroom and talking to reporters, while holding one of his books.

His resolute gaze and calm voice made him sound more mature than his age.

“It told me to just do better, to go to school more and keep reading my books. It taught me to make a change to myself,” he said.

Jorel Holland, a youth development specialist at Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center, tells reporters about how staffers are trained. It includes work with youths and hours of classrooms lessons where staffers learn about trauma, mental health and train to de-escalate situations.

While we have you, will you help us keep doing great reporting on juvenile justice?

If you like what we do and want to see more of it, please consider filling out this pledge card. Any amount is appreciated. No kidding, any amount. We need your money, but we also need you.

Here's why: Between Nov. 1 and Dec. 31, 2018, a number of national foundations including The Democracy Fund, The Knight Foundation and The MacArthur Foundation will match every dollar we raise up to $28,000. And, this generous offer extends to signing up new members. If we get 100 new members, we will qualify for a bonus.

So please consider pledging today. We will send a donation link out to you after Nov. 1. Right now, we need your name.

Thank you for supporting the JJIE and the future of journalism.

Pingback: Permanency in the News – Week of 9/3/18 – Dr. Greg Manning