On Oct. 1, the first phase of a New York state law known as “Raise the Age” took effect, meaning 16-year-olds can no longer be arrested or tried as adults. A year from now, the law will extend to 17-year-olds as well.

Authorities are just beginning to grapple with the next challenge: Where will these young offenders be housed?

New York’s Albany County, which encompasses the state capital district, is upgrading a facility in Colonie, N.Y., not far from the county jail, to accommodate the new class of youthful offenders.

Senior Investigator Shawn Noonan, the commanding officer of Professionals Standards for the Albany County Sheriff’s Office, calls it a “two-pronged approach” — and the first prong involves upgrading security.

Photo by Michael Koff/The Enterprise

The Capital District Detention Facility in Colonie, N.Y., is being upgraded in anticipation of taking older offenders, aged 16 and 17 years, following the implementation of the state’s Raise the Age legislation.

He said the new facility must take into account that some of the youths may have committed “serious crimes” and need to be held securely to avoid dangers to others, even as it seeks to make the facility “less institutionalized” in the hope of decreasing recidivism and providing troubled young people with an alternative to jail.

The Capital District Juvenile Secure Detention Facility, which primarily serves Albany, Schenectady, Saratoga and Rensselaer counties, is one of only eight secure facilities in the state, which are the only institutions qualified to take in detained 16-year-olds and eventually 17-year-olds.

New York used to be just one of two states that prosecuted 16- and 17-year-olds as adults. Only North Carolina remains. In five states — Georgia, Michigan, Missouri, Texas and Wisconsin — 17-year-olds are automatically prosecuted as adults.

Thirteen states — Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee and West Virginia — have no minimum age for prosecuting a child as an adult.

Under New York’s new law, 16-year-olds must be placed in settings appropriate for their age, rather than in jail; those charged with nonviolent crimes are to be diverted into community-based programs just like offenders who are 15 and younger.

Sixteen-year-olds arrested on serious charges will go to a youth part of criminal court and be placed in secure detention facilities for adolescents.

A 16-year-old in New York now has several different paths that he or she can follow, according to Noonan, who has been helping with several Raise the Age transitions, including upgrading the county’s juvenile facility to house adolescent offenders, as well as dealing with changes in policy for arresting and charging them.

Sent to Family Court

Any 16-year-old charged with a penal misdemeanor after Oct. 1 will be sent to Family Court, so that he or she will not have a permanent criminal record. If the youth is pulled over for a vehicle or traffic misdemeanor, or a violation, he will go to the local court.

But if that 16-year-old is charged with a felony, he’ll be sent to the newly created Youth Court.

In Albany County, the Youth Court will be in the same building as Family Court and will be overseen by Family Court Judge Richard Rivera, said Noonan.

The 16- and 17-year-olds whose cases remain in Youth Court will be known as adolescent offenders; their counterparts aged 13 to 15, known as juvenile offenders, will be tried in the Youth Court as well. According to the Raise the Age law, adult sentencing will apply, but the judge must take the adolescent offender’s age into account when sentencing, and he or she is eligible for youthful-offender treatment.

In the court system, public defenders will be trained to represent someone in the Youth Court, said Susan Bryant, the acting director for the New York State Defenders’ Association.

Public defenders are also participating in local conversations on county plans for implementation of Raise the Age, which include addressing social services, probation and transportation.

There is still concern about minors being detained as juveniles, she said.

“It’s certainly a step hopefully towards continued reform,” she said. “I’m not sure if this is the best structure for it, but we will see how it goes.”

One debate is over whether all cases should begin in Family Court, said Bryant. She noted a judge may treat a 16- or 17-year-old more like an adult since they appear older.

Judicial education is needed, Bryant said, although the Youth Court judges being trained to work with adolescent offenders may also be serving in Family Court.

Courtesy The Enterprise

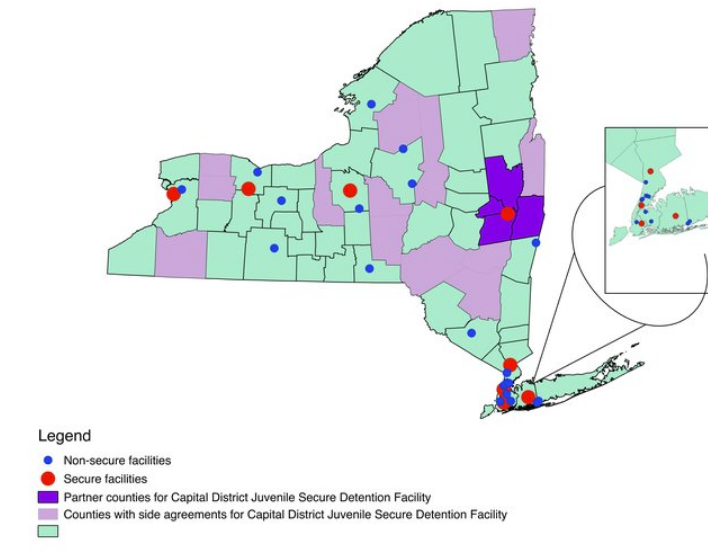

A map of New York shows eight secure juvenile detention facilities in red, which are able to hold adolescent offenders. Another two dozen non-secure facilities are marked in blue. Counties shaded in purple are in a partnership to share Albany County’s facility; those shaded in lavender have side agreements to send adolescent offenders to Albany County’s facility.

New York has two dozen detention centers for juveniles 16 and younger, scattered across the state. Under the new law, New York has eight secure facilities for adolescent offenders who are awaiting trial and for those convicted and sentenced to less than a year.

The goal is to avoid young people being held far from their homes and families, said David Condliffe, executive director of the advocacy group Center for Community Alternatives and a member of the state’s Raise the Age task force.

Adding ‘trauma to trauma’

“Imagine you’re 16 years and you find yourself hundreds of miles from home … It adds trauma to trauma,” said Condliffe.

Condliffe said incarceration has decreased in places like New York City, due to a focus on alternatives to incarceration, while incarceration has increased in rural parts of the state, an assertion backed up by data from the Vera Institute.

Sixteen- and eventually 17-year-olds who face trial in Youth Court must now be held for trial in youth facilities if a judge determines there is a need for pretrial detention. They can no longer be held in county jails as adults, but instead must be held in separate wings of secure youth facilities, or “specialized secure juvenile detention facilities for older youth.”

Adolescent offenders will be detained in county-operated facilities located in Buffalo and Rush, a suburb of Rochester, as well as in Onondaga, Albany, Westchester and Nassau counties, according to Monica Mahaffey, a spokeswoman for the Office of Children and Family Services.

They may be held at such facilities not only during pretrial detention, but also if their sentence is one year or less following conviction.

“OCFS and the State Commission on Correction certify and regulate the detention centers. Counties operate them,” Mahaffey wrote in an email to The Enterprise. “Every county is not required to operate a facility, but every county must have a facility available for its use.”

She noted that these facilities are not to be located at county jails, but can be at juvenile secure detention facilities if the offenders are separate from the younger juvenile delinquents and juvenile offenders.

Alternatives to secure facilities considered

Alex Wilson, associate counsel for the New York State Sheriffs’ Association, said that lately the association members have frequently discussed the issue of so few secure facilities in the state, especially upstate.

But beyond transportation, there are concerns about having enough beds, or places for the 16-year-olds, Wilson said.

“It certainly presents a problem,” said Bryant. Currently, she said, no 16-year-old has been sent to a secure facility.

Bryant said a number of counties are considering alternatives to using one of the eight secure facilities. For example, Tompkins County, in central New York on the edge of the Southern Tier, is considering creating a specialized secure facility to be shared among counties in the Southern Tier, she said.

On Oct. 16, the Tompkins County Legislature authorized the county to enter into an agreement to form a local development corporation to create a new specialized secure detention facility.

In April, Tompkins County joined 10 other counties in a coalition to explore Raise the Age issues, including where to house adolescent offenders.

“The problem is the law requires them to be in these specialized facilities, but the cost of every county having one just doesn’t necessarily make any sense,” Bryant said.

“But from the defense perspective we want our clients to be as close to home as possible, as close to a lawyer as possible so that they can have regular communication and aren’t being transported across the state for a court appearance.”

Wilson noted that there has been a lot of discussion on treating 16-year-olds and eventually 17-year-olds as juveniles rather than adults upon their arrest. He said that their detention will have to take place in special rooms separate from where adult offenders are detained upon their initial arrest up until they are arraigned in court.

But Wilson said that the Raise the Age legislation is written with the presumption that most young offenders will not be detained; he believes most are or will be released on their own recognizance and that probation officers and ankle monitors will be more often used than jail time.

The goal of the legislation and the presumption is that, when someone is brought into the Youth Court, they will be released, Bryant said.

But finding secure facilities for those who require it remains a hurdle.

“You’re trying to find balance,” said McLaughlin, explaining that the county cannot have too few beds or suffer as some facilities have from having too many empty beds after overbuilding.

Juvenile detention in New York has been reduced by over half since 2010 due to diversion and prevention programs, said Mahaffey.

“Raise the Age provides an opportunity for the same strategies to be applied to 16- and 17-year-olds,” she wrote in an email to The Enterprise.

This is a condensed and slightly edited version of an article by H. Rose Schneider, a 2018 John Jay Rural Justice Reporting Fellow, written as part of her fellowship project. The complete story, published in the Altamont Enterprise, can be viewed here.

Pingback: Friday News Roundup: November 9, 2018 | Justice Programs Office