Several states have announced they will continue collecting data on racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system, five months after Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Administrator Caren Harp announced the agency is rolling back these reporting requirements. The announcements came in the chat box of an OJJDP webinar focused on federal data on girls in the juvenile justice system.

One attendee commented to the webinar presenters, “We need to address the rescission of [Disproportionate Minority Contact] guidance — are [you] going to keep tracking DMC and how?”

Iowa Department of Human Rights Executive Officer Kathy Nesteby, who was attending the webinar, responded, “Although OJJDP won’t be requiring DMC matrices to be submitted, Iowa is going to keep doing them for our own use at the state level and to maintain continuity with previous data we’ve produced.” Representatives from Illinois and Washington state responded that they would also continue collecting data.

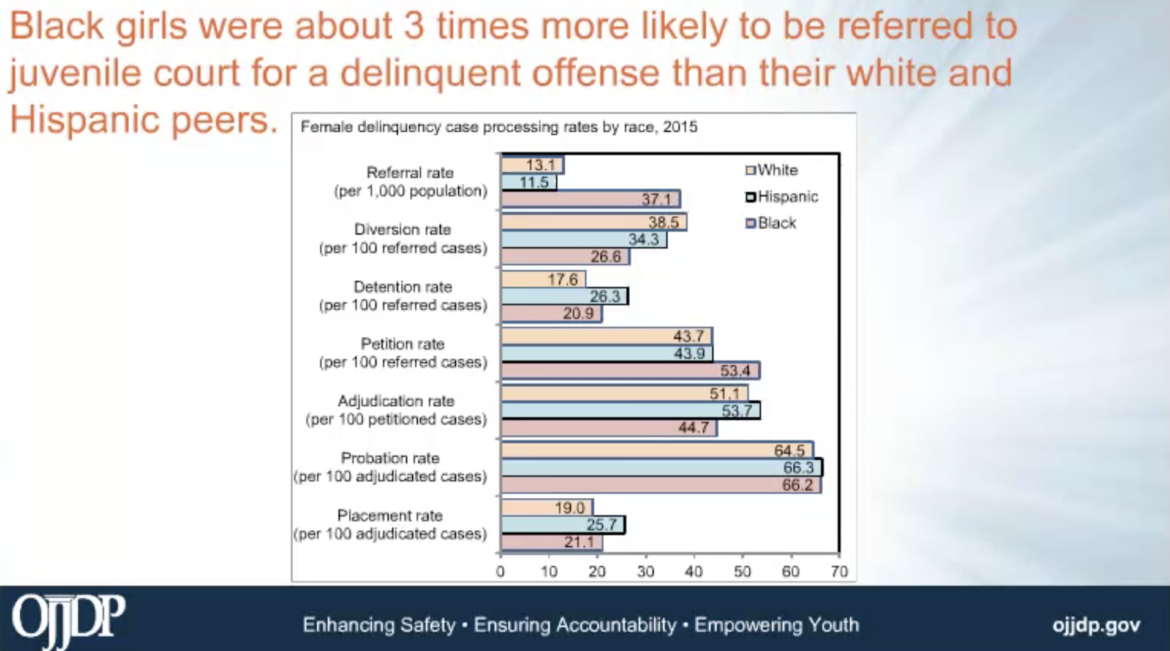

The comments came during a presentation that largely highlighted the dramatic racial disparities at all points of system contact for girls. The over-representation of black girls in the juvenile justice system is an irrefutable and ongoing injustice — despite making up 15 percent of the youth population, black girls are 35 percent of girls’ delinquency cases.

Social science analyst Benjamin Adams (until recently at the OJJDP, now at the National Institute of Justice) shared the most recent available data on delinquency case processing rates by race for girls, showing that black girls are nearly three times more likely to be referred to juvenile court for a delinquency offense than white girls. Relative to their black and Hispanic peers, white girls are more likely to have their cases diverted; less likely to be detained, and less likely to receive a disposition of placement.

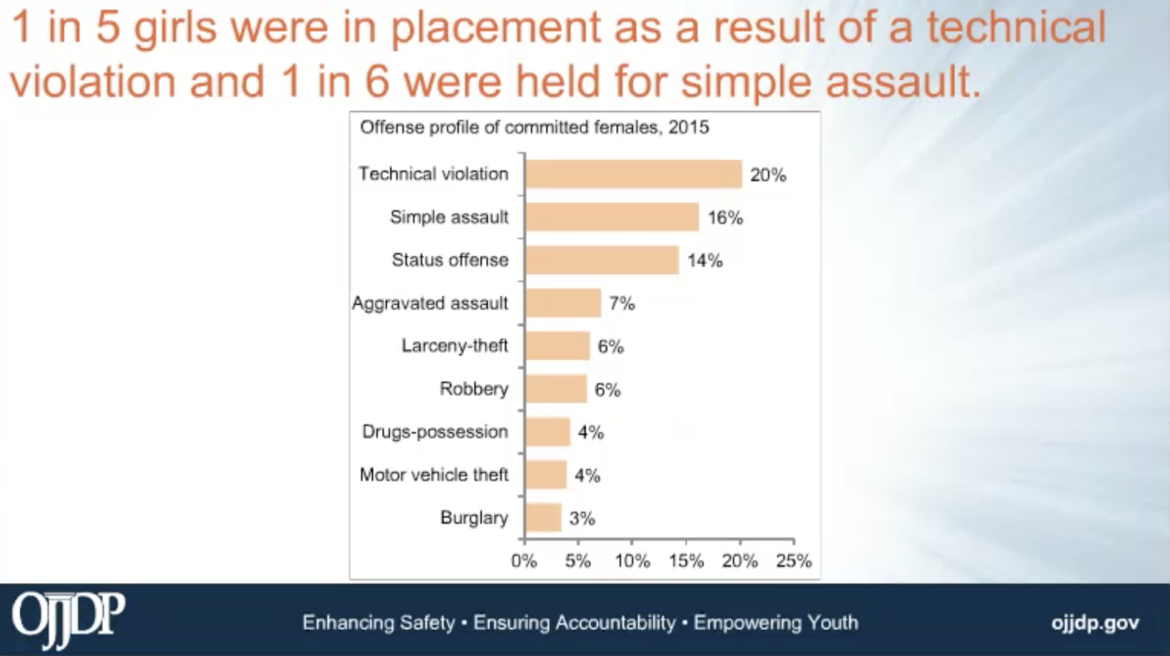

This over-representation coincides with the general overincarceration of girls for predominantly nonviolent offenses. The top three offenses for committed girls — the deepest end of the system, ostensibly for youth with the most serious offenses — are all nonviolent crimes: technical violations, simple assault and status offenses. These nonviolent offenses make up the most serious charges for a full 50 percent of committed girls.

A technical violation is a violation of probation — including failure to pay restitution or missing a mandated curfew. A status offense is a crime based on age — charges like truancy and running away that are only crimes for minors. In 2015, truancy charges accounted for nearly 60 percent of girls’ status offense cases. Girls can be arrested for simple assault as an unintended consequence of mandatory and pro-arrest domestic violence policies.

These are the charges leading girls — and predominantly girls of color — to receive the most serious consequences of the juvenile justice system.

But OJJDP’s new priorities are misaligned with these realities. Administrator Harp has said the agency has been too focused on “avoiding arrests at all costs and therapeutic intervention” and “providing services.” Yet these data show girls getting arrested and moving deeper through the system are not a threat to public safety, and would likely be better served by services and interventions than by expensive and harmful incarceration. This is a view shared by victims of crime, who support serving youth in the community, including young people involved in violent crime.

Continued over-representation of youth of color is a call to action for a strengthened approach to reducing racial and ethnic disparities, not a more “simplified” approach.

Attendees of the webinar made clear where the agency could highlight new priorities in their research and data collection: improving data on Latinx youth, who are counted differently across different data sets; adding data on sexual orientation, and addressing the absence of data on youth who identify as nonbinary.

Hopefully more states will join Illinois, Iowa and Washington in committing to continue collecting racial and ethnic disparity data and ensuring that data can be disaggregated by gender. There are already existing, critical data challenges. We should be addressing those data gaps, not creating more.

Sara Kugler is the director of advocacy and communication at National Crittenton.

Thank you for this information. Just wanted you to know that Florida Department of Juvenile Justice is also maintaining its collection of DMC Data, for it is valuable in emphasizing need, as well as helpful in allocating funds to address DMC throughout the state.