![]() The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges released a bulletin last October that details the importance of data in developing effective school-justice partnerships. In the report, NCJFCJ laments that “poor data collection and management strategies” often hamper the effectiveness of school-justice partnerships aimed at disrupting the school-to-prison-pipeline.

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges released a bulletin last October that details the importance of data in developing effective school-justice partnerships. In the report, NCJFCJ laments that “poor data collection and management strategies” often hamper the effectiveness of school-justice partnerships aimed at disrupting the school-to-prison-pipeline.

Colin Slay

Those familiar with the Clayton County, Ga., model of developing school-justice partnerships know that the Clayton County Juvenile Court has been a devotee of the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative. One of the core strategies of JDAI is the robust use of data. Adequate data collection and reporting are essential to establishing benchmarks, making decisions and measuring outcomes for any reform effort.

In our experience with assisting jurisdictions in replicating the Clayton County model of developing school-justice partnerships, we have found the data discussion to be central to understanding the scope of the problem and in identifying strategies for curbing school-based referrals to the court. It is also very helpful in winning support from skeptical stakeholders. I cannot count the number of times I have witnessed a conversion of sorts — nonbelievers confronted with data who are no longer able to deny the problem. The use of solid data has created some of the most ardent supporters of school-justice partnerships; sometimes from some of the loudest skeptics in the room.

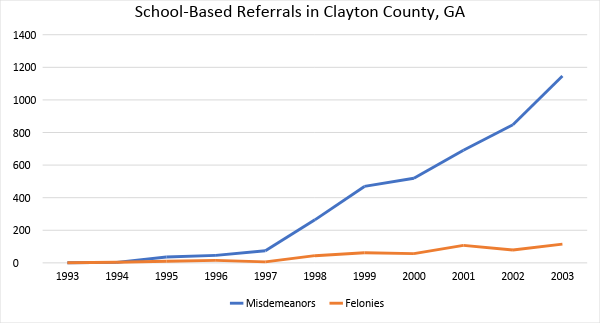

In our own experience, Clayton County endured a shocking 1,200 percent increase in school-based juvenile complaints within a few short years of the creation of our school resource officer program.

We didn’t have to dig too deeply to see the likely causal factor — the introduction of a full-time police presence on campus in the previous years. That revelation from the data helped us focus our early reform efforts on reducing school-based arrests. And when we dug even deeper, we realized that the vast majority of those complaints involved only a handful of charges. Again, that knowledge allowed us to focus our attention, which was instrumental to us gaining the cooperation of our partners in the schools and law enforcement. Thanks to the data, we didn’t attempt to change the entire relationship all at once, just a small part of it (at least at first). People were more comfortable with that. It was low-hanging fruit.

It wasn’t always easy, however. We ran into some obstacles along the way. For instance, understanding one element of data often begs other questions, and we sometimes found that we didn’t have the information necessary to answer them. Through collaboration we were often able to get the missing data from partners, but at times we had to just create new collection systems.

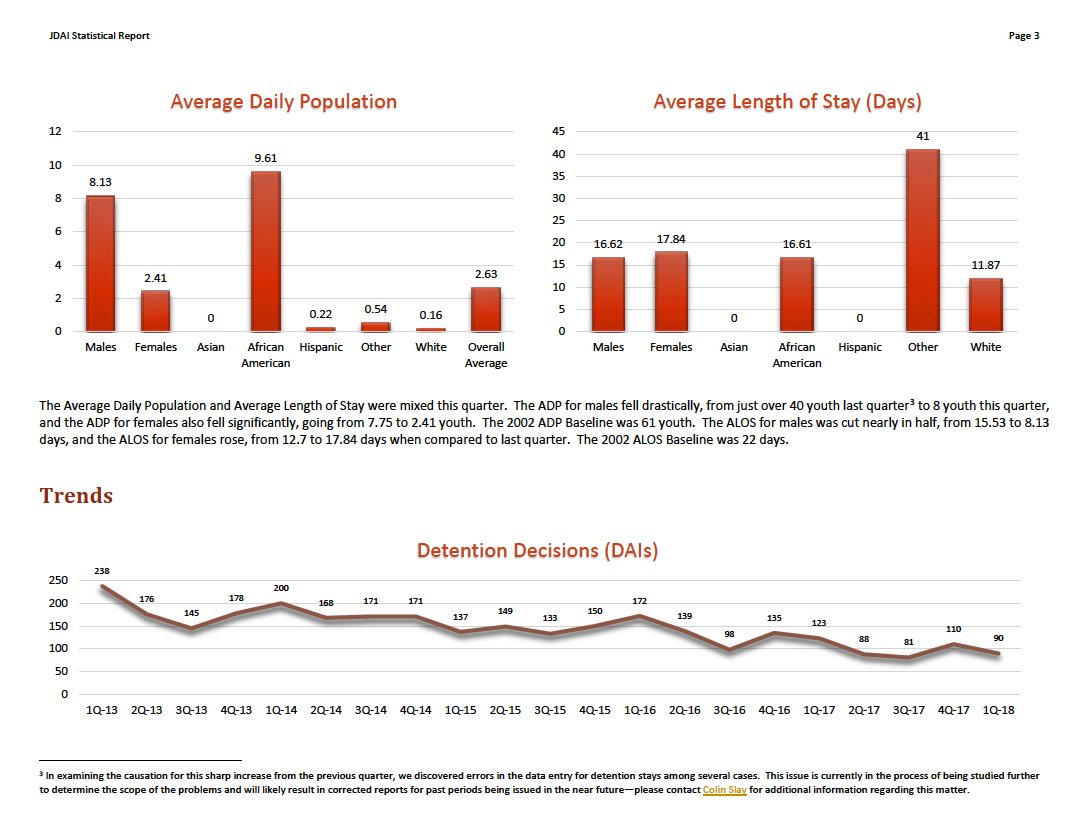

We also had to design methods for effectively sharing the data with the various decision makers (which oftentimes meant making it visual with graphs and charts and creating a narrative story to explain the tables full of numbers — see Figure 1). We developed several reports that measured outcomes and tracked progress over time, and we found these essential to solidifying our early gains. That proved helpful in making our stakeholders more comfortable in branching out into new areas of reform.

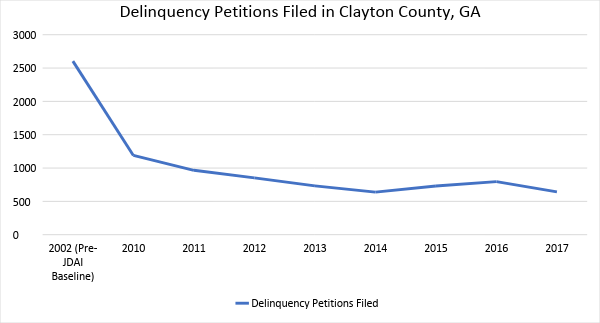

It’s been nearly 15 years since the implementation of that initial agreement, and we have reduced overall complaint numbers by more than 70 percent.

Our agreement has been modified a few times, and each time it was data that helped us broaden the scope. The data revealed our successes and indicated areas where we could push deeper. It was also helpful in identifying areas where training was needed. From the start, data has been central to our entire program — I do not think it is possible to understate the importance of good data collection and sharing in school-justice partnerships.

NCJFCJ’s bulletin offers sound advice on data collection and sharing as it relates to developing school-justice partnerships, and I encourage anyone who is interested in disrupting the school-to-prison-pipeline to review the report. I think you will find it very helpful.

Figure 1: Sample of Clayton County Data Report

Colin Slay is the director of juvenile court operations for Clayton County, Ga. He is a 2011 graduate of the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Applied Leadership Network and has helped provide technical assistance to 50-plus jurisdictions looking to replicate Clayton County’s School-Justice Partnerships Model.