Video by Roger Newton

JACKSON, Miss. — Mississippi’s capital city is becoming a petri dish for an experiment designed to stop an epidemic of gun violence that claimed 84 lives in 2018 and took 16 less than two months into 2019.

If successful, it could serve as a model throughout the South and perhaps the nation.

Uproar over the Jan. 13 shooting death of a pastor as he was unlocking the doors to his sanctuary for Sunday services elicited the usual calls for gun control in a state that touts its open carry laws.

But approaching the issue of gun violence from a Second Amendment perspective has been ineffective.

Another approach is needed, said Howard Henderson, a professor at Texas Southern University, and the director of The Center for Justice Research, which looks at gun violence from a public health perspective.

Henderson became interested in Jackson after reading stories in the Clarion Ledger, Mississippi’s statewide newspaper, about the rise in homicides and what the city was doing to curb the violence.

He and many medical professionals, such as the American Medical Association, are beginning to approach gun violence from a public health perspective, one that requires a comprehensive public health response and solution. It begins with data-gathering and research to understand the cause and effect of gun violence on the community, similar to a scientist studying an infectious disease to prevent it from spreading.

“To prevent something from occurring, you need to have the facts, that’s pretty much what preventative medicine does; it minimizes trauma,” Henderson said. “When you think of it from a public health perspective, you want to prevent the spread of infectious disease. Well, what is gun violence but a virus, which traumatizes not just those involved with it directly, the shooter and the victim, but the community as well.”

Public health perspective

And Jackson could see itself on the forefront.

Backed by self-described radical Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, Jackson area medical professionals like trauma surgeons plus professors and educators, church leaders, police, community activists and ex-offenders are sharing a seat at the table to find a way to mitigate the trauma.

“Just like any other health issue that we look at, it will take data collection and data sharing and cooperation among state agencies to address gun violence,” said Roy Mitchell, the executive director of the Mississippi Health Advocacy Program.

Since its inception more than 20 years ago, the MHAP has been involved in major consumer health policies in the state.

“We deal with a lot of data and analysis, and I haven’t seen anything related to gun violence — which, make no mistake, is a public health issue,” Mitchell said.

Roger Newton

Benny Ivey, a former area gang leader, is working with the violence interruption program in Jackson.

Matt Kutcher, a trauma surgeon at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, one of two Level 1 trauma centers in the state, sees hundreds of trauma patients a year, many of them suffering from gunshot wounds.

“We see people at their worst. Gunshot victims and their families. Many times there’s nothing we can do. I think that for many of us, it leaves us unsettled. It’s our job to help people, and when we’re not able to do that, it makes you wonder what else can be done,” he said.

“I believe there are a number of things we can do,” Kutcher continued.

“I’m not arguing about taking away anybody’s rights to own a gun, but about ways we can do a better job as medical professionals to prevent what can be prevented, such as accidental shooting deaths.

“We tell diabetic patients what socks to wear. It’s all based on research and data, and what we know will help the patient. Why can’t we do that for gun injuries?” he asked.

[Related: Community Activism a Family Tradition for Head of Violence Interruption Program]

Jackson: ‘The capital of Southern violence’

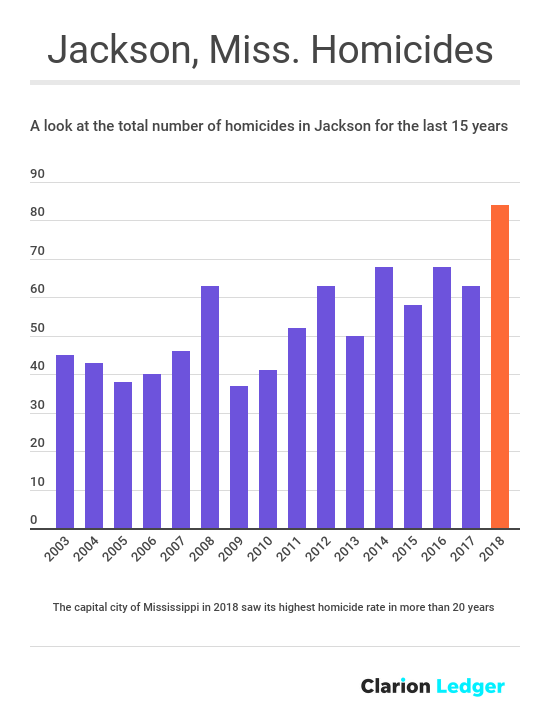

Jackson’s 84 homicides in 2018 was the highest in more than 20 years and an almost 24 percent increase over the previous year. Almost all those slayings — 96 percent — were shooting deaths.

Jackson was the only city in the region to see such a homicide rate increase, ultimately ranking it as one of the deadliest cities, not just in the South but also in the nation, based on population. Memphis, the only other Southern city to register an increase, saw homicides rise 5 percent — from 176 slayings in 2017 to 184 in 2018. For Memphis, 2016 was the deadliest year recorded in the city in the last two decades with 228 homicides.

Not surprisingly in the gun rights South, discussion of gun control — even after a pastor’s shooting death — is mired in entrenched political viewpoints.

The Rev. Anthony Longino, the 61-year-old pastor of New Bethany Missionary Baptist Church, arose from bed on that Jan. 16 morning, put on his Sunday best and drove his Dodge Ram pickup to his Jackson church.

Many residents call New Bethany a beacon of hope in a troubled neighborhood, an area split nearly equally between abandoned, dilapidated structures and homes with barred windows and doors.

At least three Jackson youth approached the pastor that morning as he attempted to unlock the padlocked front doors. They demanded money and Longino’s truck before gunning him down. Longino bled out on the walkway.

The Jackson pastor’s death sent shockwaves through a community that had seemed desensitized to an all-too-common reality in the capital city, gun violence deaths.

The state’s governor, Phil Bryant, criticized city leaders in a tweet.

“It is time for our leaders in the Capital City to act. I will join them to stop this violence together or will do so as Governor on my own. This must end,” Bryant said.

Barbara Gauntt/Clarion Ledger

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, left, and Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, right, at a press conference in Jackson in November.

Mayor Lumumba held a news conference to discuss his administration’s approach to crime moving forward. He has resisted a purely law-and-order response that puts the solution in the hands of police alone. Instead, he has asked the community to get more involved. He stood beside his sister, Rukia Lumumba, when she introduced a program tailor-made for Jackson, one that has seen success in larger cities by confronting violent crime in the neighborhoods where it occurs the most.

Credible messenger program relies on locals

Terun Moore was paroled on Oct. 12, 2017, after serving 19 years in prison, including time served before his trial. He was sentenced to mandatory life without parole, the only alternative to the death penalty for a capital murder conviction in Mississippi. However, because the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012 ruled such sentences for defendants 17 or younger were unconstitutional, a new trial was ordered, and Moore, who was 17 when the crime occurred, was released on parole.

Now, Moore says he is committed to turning his life around, helping others and stepping in to assist the Jackson Police Department in neighborhoods where residents are suspicious of the police and less willing to cooperate.

“We don’t have those relationships with the police, so people in those neighborhoods are going to trust us. We can let them know we understand where they are coming from. We can’t reach everybody …” Moore said, his voice trailing off.

“We can’t reach everybody, true, but if you reach just one, you’ve made a difference,” said Benny Ivey, a former area gang leader, completing Moore’s sentence.

Moore, Ivey and Valencia Robinson are led in the violence prevention effort by Rukia Lumumba, who returned to the city she grew up in after learning the ins and outs of the credible messenger and violence interruption programs in New York City, where the program and similar offshoots started.

The goal is to spread the program in neighborhoods that need it so that those who know when there’s a potential for violence can be enlisted to reach out to messengers and other program officials to step in and “interrupt” the cycle of violence.

Roger Newton

Rukia Lumumba always planned to come back to Mississippi and facilitate programs to help the community.

“We want someone that’s experienced and similar in experience to those they are mentoring. Similar to any health crisis issue, such as addiction, you want to have people who have gone through it and so can guide them through it,” Lumumba said.

Stabilizing people so that violence does not return is also a goal. Helping others navigate necessary conversations and getting them essential resources to gain the tools that can resolve rage is equally important, she said.

At the heart of violence, Lumumba said, is unacknowledged anger at an inability to provide for basic needs, financial hardship and a lack of conflict-resolution skills.

“They [schools] are not teaching that anymore. We’re teaching people how to take a test. We’re not teaching our people social skills,” she said, adding that children in school cannot talk in class, in the hallway or the lunchroom.

At what point, she asks, do young people learn how to communicate with each other?

Lumumba gives an example of the scenarios that may cause people to live in a constant state of suppressed anger. She refers to a study on Mississippi’s economic conditions by Operation Hope.

“It said, in Mississippi that you need to make $14.84 an hour in order to pay your rent. That’s on average for anybody. So people are stressed, people are tired, and people are on edge,” she said, pointing out that most people in Jackson have to work two to three jobs to be able to afford a place to live.

Once the program is fully implemented, Lumumba predicts tangible results in one to two years. In the meantime, she reiterates that using the same methods as now will not work.

“If we replicate the same behavior it becomes part of our normal way of functioning. It’s transmitted just like a disease is transmitted. It becomes part of our DNA,” she said. “We have to shift the way we deal with it. Locking people up has never proven to be the answer. It does not get to the root of our issue and it does not treat the epidemic in the proper way.”

‘This is an issue that we can’t just outpolice’

Justin Vicory

Terun Moore, a former inmate, is part of a new program working to interrupt violence in Jackson, Miss.

These violence programs, developed at the grassroots level by community activists, scholars and medical professionals, have shown success at preventing interpersonal or domestic violent crime.

Similar to other cities, a majority of Jackson homicides — about 80 percent — are characterized as interpersonal or domestic, where an argument escalates to murder.

The John Jay College of Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation Center, along with help from the New York City Police Department and that state’s department of health, studied the effect of a similar program called Cure Violence.

The 2017 study tracked gun injury data in New York City neighborhoods for 72 months before and after the program’s implementation. It found gun injury rates fell by half while the matched comparison area experienced a 5 percent decline in the same time period.

The study also found the program didn’t just reduce violent crime but helped change the attitudes of the community in a positive direction — a difference of about 30 percentage points between communities with a program and those without, according to a 2016 study in Baltimore.

“One of the keys is to look at neighborhoods with similar demographics, the same economics, and if they don’t have the same rate or kind of violent crime, then to mimic those neighborhoods, find out, study, research what they do and do that,” said Juan Cloy of Jackson, an advocate for juvenile justice and criminal justice reform.

“This is an issue that we can’t just outpolice,” said Cloy, who is running for sheriff of Hinds County, where Jackson is the county seat. “It took more than 20 years for me to realize that the police serve a very important role, but it’s one that is reactionary. We’re dealing with a virus and you need more than the police, you need medical professionals to prevent its spread.”

No national study of data

It goes back to gathering data. Jackson has started that process.

Last summer, Jackson officials approved an agreement between the Jackson Police Department and Jackson State University to study gun violence. The first step is to gather data, something the city has had problems with until recently, when it unveiled a new online data compendium that tracks crime all the way down to the street level. The premise is that by identifying where crime is most likely to occur, organizations can mobilize to prevent it from occurring.

Henderson, the Texas Southern professor, is tracking statistics himself in the absence of a national study that has languished for years.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks firearm deaths nationwide. However, the agency has been hamstrung from conducting research into the underlying causes of gun violence since 1996. An amendment to the annual appropriations bill for the CDC stipulated that “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the [agency] may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” It has appeared in every CDC spending bill thereafter, despite the agency’s statistics that show firearm fatalities are continuing to increase.

Since 2005, firearm fatalities in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee have been about twice as high as the national average. Statistically, residents of these states are about twice as likely to die by firearm than other regions of the country, whether it’s an accidental shooting, suicide or homicide.

As with the CDC, there is no funding devoted to examining gun violence and firearm deaths at the Mississippi Department of Health. Similarly, there’s no educational campaign by the state’s Department of Public Safety. Instead, a Google of firearms deaths on the DPS website brings up what you need to know about concealed carry and firearm permitting, or how to carry a firearm in Mississippi.

Think seat belts.

The federal government used a multipronged approach, one that involves technology, education and the law to reduce the public health risk of traffic deaths.

It first studied the issue from every angle, to see what human, environmental and vehicular conditions might be at play that would increase the likelihood of a traffic fatality.

A national educational campaign ensued to educate the public on what could be done to prevent traffic deaths, followed by legal efforts across the country to increase seat belt use. It worked. Seat belts save approximately 15,000 lives a year, according to the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration.

Motor vehicle deaths have been on a steady decline. The opposite has occurred with firearm deaths.

In 2017, firearm deaths surpassed the number of traffic deaths in the country, by increasing to 12.2 per 100,000 residents, compared to a rate of 11.9 traffic deaths per 100,000 residents, according to the CDC.

Texas Southern University

Howard Henderson

In the effort to follow a similar approach on gun violence, a lot needs to be done, Henderson said. He is digging into statistics himself with the ultimate goal of creating a national database to educate the public on the causes and symptoms of gun violence.

Jackson could be the test case for the South.

“You can say Jackson is the capital of gun violence in the South,” Henderson said. “The problem has always been that nobody is stopping the bleeding. You’ve got to stop the bleeding at some point. Otherwise, it’ll continue to be an epidemic in our country without a cure.”

This story was produced in conjunction with the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting. It was also published by the Clarion Ledger.

It is part of the JJIE’s project on Targeting Gun Violence. Support is provided by The Kendeda Fund. The JJIE is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.