JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — In 2018 Jacksonville was the per capita murder capital of Florida. But that barely made news, since Jacksonville has been the murder capital among large cities in Florida since 2001.

With the mayor's election on Tuesday, the city has a choice: Keep doing what it’s doing, or try a different tactic.

In 2015, Republican Lenny Curry won a narrow victory to defeat incumbent Democratic Mayor Alvin Brown. In the weeks before that election, there was an outbreak of crime, including a school bus shooting hours before the candidates had a debate.

While mayor, Curry has refused to raise taxes to fund programs that could address the root causes of crime, but supported sending more money to the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office. Currently, polls show him beating all challengers by double digits.

A.G. Gancarski

Jacksonville, Fla., City Councilwoman Anna Brosche at event in March.

City Councilwoman Anna Brosche, who is running against Curry, has tried to blame him, saying there is a “Curry crime wave.”

Former Jacksonville area Public Defender Bill White believes Curry’s record hasn’t been meaningfully challenged nor has the record of Sheriff Mike Williams, who also seems to be cruising to an easy re-election.

There were 126 murders in Jacksonville in 2018, which was lower than the 137 in 2017 but higher than the eight years before that. While cities like Miami had more total killings, Jacksonville has the highest murder rate per capita of any large city in Florida. There is broad consensus on why this is happening, but disagreement over whether it can be fixed.

“We know what the problem is,” said University of North Florida criminology professor Michael Hallett, who has studied the crime rate in Jacksonville extensively. “We know what needs to be done. There just hasn’t been the political will to do it.”

The city puts all its resources into law enforcement, police and the county jail, he said. The only way to reduce the crime rate, he argues, is by attacking the root causes of crime, getting to at-risk children and adults before they commit a crime and steering them in another direction.

That takes money, and the city has never been willing to invest in programs and mental health counseling, Hallett said.

“Kids on the Southside have structure and things to do,” he said. “That structure doesn’t exist in many places on the Northside.”

The Southside of Jacksonville is predominantly white and middle class to wealthy. The Northside is predominantly African American and poor.

As a further example, Hallett also points to the Duval County Jail. It is, he says, the biggest mental health provider in Northeast Florida, which means people aren’t getting treated until they’ve already been locked up.

Claire Goforth

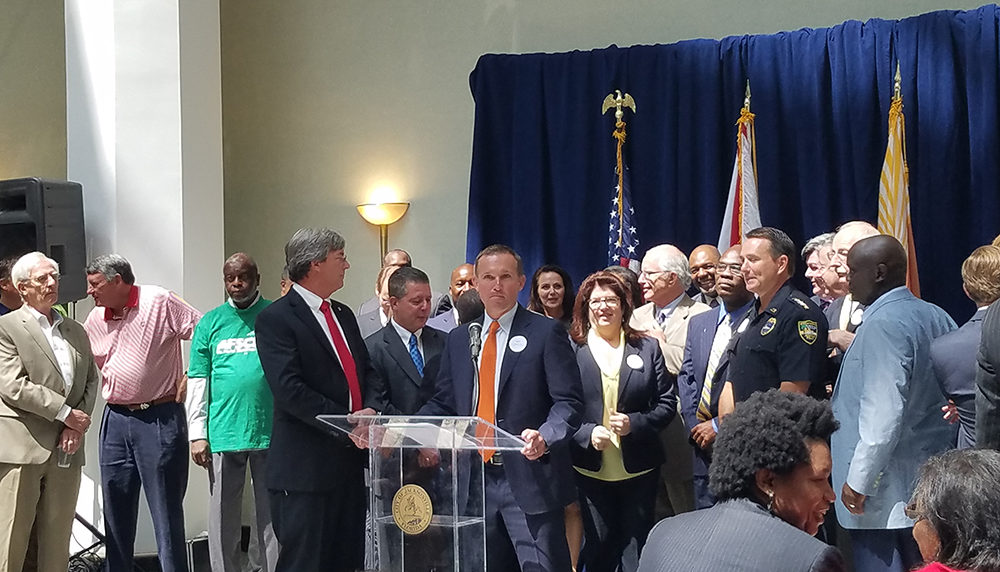

Mayor Lenny Curry (at lectern) speaks at an August 2016 press conference at the Jacksonville City Hall. Sheriff Mike Williams in blue uniform is standing on his right.

The candidates respond

Brosche said via text message that if she were mayor she would work to reduce violence by increasing the focus on prevention and intervention, rather than merely enforcement, as she believes both Williams and Curry have done. Her plans include expanding children’s programming, adding park managers and reinstating a youth employment program for children ages 14 and older.

“I would also strengthen our neighborhoods services,” she said. “I would use GIS [geographic information system] mapping information, overlay census data, then take the combined data into the community and understand our street-level leaders and community organizations to develop a comprehensive assessment of needs, challenges, and ideas. There is tremendous wisdom in the community and we must engage everyone in an all-hands-on-deck approach to reducing crime.”

Curry did not respond to requests for comment sent to his chief of staff, spokesperson and official email address.

In an emailed statement provided by a spokesperson for the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office, Williams said that while people tell him they feel safe in their neighborhoods, citizens understand that violent crime is largely driven by a “criminal element,” comprising a small number of individuals involved with “street culture drug trade.” “This relatively small portion of our population operates within a violent cycle of victimizing itself over and over again,” he said. “This is a community concern and one that will take a community solution.”

While enforcement is necessary, Williams acknowledged that arrests alone do not address the root causes of violence and said that if he were elected to a second term, he would focus on areas hardest hit by gang, drug and violent crime, work to get illegal guns off the streets and strengthen partnerships within neighborhoods.

Lack of resources

White said the answer to the city’s murder problem rests with economic inequality and racism.

“It’s still one of the most segregated cities in America,” he said. “It’s the frustration of an African-American community that still has substandard schools and infrastructure.”

There are areas on the Northside that don’t have grocery stores or other amenities that are common in other parts of town, including reliable garbage pickup, White said.

Lawanda Ravoira, president and CEO of the not-for-profit Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, said resources that exist in other cities aren’t available in Jacksonville.

“It is just the absolute lack of community-based services, especially when it comes to treating mental health,” she said. So many people in the city have unaddressed mental health issues or unaddressed trauma or other health issues that aren’t dealt with.

“What’s going on seems like a Band-Aid,” Ravoira said. “Until we address the real issues, we’re never going to solve this problem.”

In South Florida and other places there’s a specific taxing district for community services, but Jacksonville doesn’t have anything like that. Meanwhile, programs that work in Jacksonville end up being defunded. And programs like Big Brothers Big Sisters are great, but they don’t get to the kids that are most in need of help, Ravoira said.

A chance for improvement

Allison Defoor, a former sheriff, prosecutor and judge, believes Curry, Williams and State Attorney Melissa Nelson have the best chance to improve the situation.

Now an ordained minister and criminal justice reform advocate, Defoor said Jacksonville’s biggest problem has been a reluctance to change, and a lack of communication and coordination between various elected officials and agencies.

But the current elected officials are changing that, he said, with Curry, Williams and Nelson all broadly supportive of reform efforts that would seek to reach people before crimes are committed.

Last month, the three met with representatives from Chicago-based Cure Violence, an anti-violence program that relies on intervention by community members to stop the onslaught of murders and other violent crimes. Curry invited the organization to do a preliminary assessment in Jacksonville. All indicated their support for the groundbreaking program that utilizes a public-health based approach to address violence, though a few members of the community were skeptical of the election-season timing of the announcement.

Defoor said he hoped Jacksonville would look at Miami, which have seen improvements by starting drug courts and mental health courts that keep people out of the regular court system.

And by keeping people out of the regular criminal justice system, people are less likely to reoffend, he said.

Ben Frazier, a civil rights activist and founder and president of the Northside Coalition of Jacksonville, said the city needs to find a way to reach people before they need to be arrested.

“We have to connect the dots between crime, poverty, mental health, education and other things,” he said.

When the organization talks to people involved in criminal activity, they say they can’t find jobs and want to be employed, Frazier said.

“Treat crime like a public health issue,” he said. “It’s a disease, no different than TB or anything else.”

The latest statistics he’s seen show that in the 32209 ZIP code, part of the city’s Northside, 47 percent live in poverty and 12 percent are unemployed, Frazier said.

“Dealing with this will cost money one way or another,” he said. “We can spend it on helping people or we can spend it on locking people up.”

Claire Goforth contributed to this story.

This project was collaboratively produced with Jaxlookout and underwritten in part by The Vital Projects Fund and NewsMatch funders like you.