It’s now been three years since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Henry Montgomery should have a chance to earn parole, because he’d been a teenager at the time of his crime.

But on Thursday, the Louisiana parole board voted against parole for Montgomery for the second time. So Montgomery, now 72, will remain in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, working five days a week at the prison silk-screen shop, as he has for decades.

“I’m almost at a loss for words at how it is possible that Henry, yet again, was denied. One would have thought that he would be one of the first,” said Marsha Levick, chief legal officer of the Juvenile Law Center.

The high court’s 2016 decision — Montgomery v. Louisiana — impacted 2,600 prisoners across the nation who were serving what’s known as JLWOP — juvenile life without parole — for crimes they’d committed as teenagers. Those figures are from The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth (CFSY).

Over the past three years, hundreds of prisoners with JLWOP sentences have been granted parole and released. Hundreds more have been resentenced and will have the chance at parole in coming years.

Juvenile Law Center

Marsha Levick

In states like Pennsylvania, which had the nation’s highest numbers for juveniles with life sentences, the parole-hearing release rate is about 75 percent in so-called Montgomery cases, according to the Juvenile Law Center. Generally, parole boards in these cases are given distinct criteria to follow that go beyond the crimes committed to recognize growth, maturity and rehabilitation that the former teen now displays.

“I think Henry Montgomery meets the criteria. Yet he remains held back,” Levick said.

A compliment and recommendation

In 2017, Montgomery was resentenced to life with possibility of parole by a judge who called him a “model prisoner.” Still, many others serving JLWOP sentences had already been released by last year, when Montgomery was granted his first hearing. The parole board denied him, in a 2-1 decision that seemed rooted in opposition from the family of his victim, a parish deputy, because the state’s powerful law enforcement organizations had also submitted letters pushing for a denial.

Last year, the parole board officially recommended that Montgomery complete more programs before they would consider release.

Then, recently, Montgomery was given another date. To have a hearing slated so quickly on the heels of the first one seemed like a good sign. He’d completed all the programs that the Department of Corrections had recommended. On Thursday, his lawyer and his friends at the Louisiana Parole Project felt hopeful.

“We were certainly optimistic,” said Kerry Myers, the Parole Project’s deputy executive director, who had arranged for Montgomery to come through the Parole Project immediately upon release. Because of Montgomery’s age, they’d created what could be called a geriatric reentry plan. After Montgomery had sufficient time to adjust to “the free world,” he would move into a faith-based mission in a small Louisiana town. “He could stay there for the rest of his days,” Myers said.

The board again voted against Montgomery in a 1-2 vote, with two votes for his parole and one against him.

The sole opposing member, Brennan Kelsey, said Montgomery needed to complete more programs before he could be seen as eligible for parole. “It’s your responsibility to continue to work,” he said in the hearing.

Louisiana Parole Project

Keith Nordyke

Montgomery’s lawyer, Keith Nordyke, was baffled by the decision. “I was really floored,” he said. “I don’t know what else he can take that is relevant to him.” He mentally ran through a list of possible programs at Angola: parenting classes that don’t seem to make sense for a 72-year-old man without kids. Substance abuse classes that don’t apply to Montgomery, who has never struggled with addiction. Classes for a GED that Montgomery will never be able to pass because of his cognitive limitations.

Over the past few years, Nordyke has represented a large number of other prisoners serving JLWOP who haven’t been denied. “And many of them have done the same programs as Henry,” he said.

Montgomery live is quiet

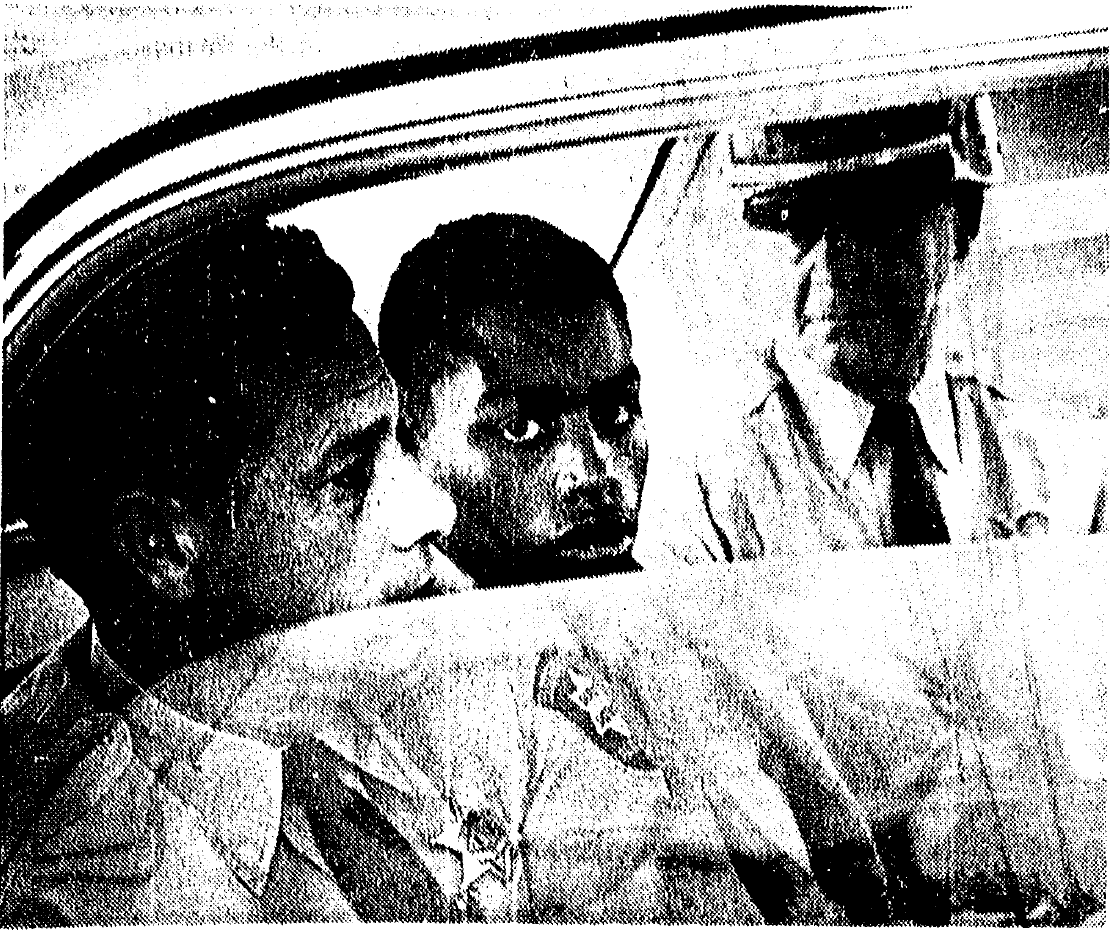

On Thursday, Montgomery appeared before the parole board in a video feed from Angola, where he’s spent most of his life.

He’s now served 55 years in prison for a first-degree murder conviction. From the video feed, the parole board and its audience saw a gray-haired, bespectacled man wearing a prison-issue hearing-aid box hanging from a lanyard around his neck. The box looks like a repurposed cassette-tape player; it’s basically an amplifier that helps him adjust for increasingly poor hearing.

Nordyke was with him, to help translate the questions heard over video. But Montgomery struggled when questioned about rehabilitation or asked what he had learned from certain programs.

Louisiana Parole Project

Kerry Myers

Even on his best days, Montgomery has few words. All the prisoners who have served alongside him say that he’s steadfast, in a way that’s displayed through his work and his consistency throughout the years. Even people who had served decades in the same prison dorms didn’t remember much about him, beyond that he was quiet.

“Henry is a unique humble person," Myers said. "But he is not articulate. He was nervous. So he struggled to express himself.”

In the mid-1960s, Montgomery went through two trials in East Baton Rouge Parish for the murder of Deputy Charles Hurt. Though the narrative is murky, it seems that, on that day in 1963, Hurt was flushing truants from a span of tall grass in a park and that Montgomery was startled from what may have been a nap. Reports from the school and family indicate that Montgomery was likely bullied, leading him to carry a gun. He was called “Wolf Man” because of outsize incisors and was failing academically because of his serious cognitive limitations.

Whatever the circumstances were, Montgomery made a split-second mistake and killed Hurt, who was known as a fair-minded person in the largely African-American community that he patrolled.

At the first trial, Montgomery was given a death sentence, which was overturned.

When jurors again convicted him, he was automatically sentenced to life without parole. That was then the law in Louisiana — and remained the law in more than half of states until the laws were thrown out by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 2012 Miller v. Alabama decision.

His life at Angola

When Montgomery was shipped to Angola, he was told he would be there until he died.

Back then, the prison didn’t offer many programs, especially for people like him with a life sentence who would never leave the prison’s walls. In response, Montgomery started a boxing program that he helped lead for decades, gaining a reputation as a quiet but staunch coach.

And — though his own trial lawyers described him as “a slow learner,” with a borderline IQ, in the 70s — Montgomery organized a literacy program that allowed other prisoners to excel in reading and writing while he worked alongside them, learning what he could.

Even when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Miller decision that teens could no longer be automatically sentenced to life, Louisiana courts refused petitions for parole from people who were already serving life sentences for crimes they committed before they’d turned 18.

In 2016, in the Montgomery decision, the high court ruled that their decision’s effect should be retroactive and that prisoners like Montgomery should have a chance to earn parole.

How teenagers are different

Montgomery is part of a set of U.S. Supreme Court decisions that instruct lawmakers and courts to consider teenagers differently. In those decisions, justices have carefully outlined how the brains of youth are still developing, which makes them more susceptible to acting rashly. But also, the court found, because teens are still a work in progress, they have greater capacity for rehabilitation.

Only the rare, incorrigible, person would likely be deserving of a JLWOP sentence, the court found.

“The penological justifications for life without parole collapse in light of the ‘distinctive attributes of youth,’” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in the Montgomery decision, which outlined the science about still-developing adolescent brains, which causes adolescents to be impulsive but also gives them capacity for change.

Every “Montgomery case” involves a murder with loved ones who can’t return. So the parole hearings aren’t simple. Still, since the decision, parole boards, legislators and judges across the nation have set free about half the 2,600 inmates serving life without parole for crimes they committed as juveniles, according to the CFSY.

But on Thursday, Montgomery needed a unanimous decision and did not get it. That means he cannot be released and reconcile his wrongdoing with his community, Levick said, reading out loud a passage from one of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions about juveniles, Graham v. Florida, where Kennedy wrote:

“Life in prison without the possibility of parole gives no chance for fulfillment outside prison walls, no chance for reconciliation with society, no hope. Maturity can lead to that considered reflection which is the foundation for remorse, renewal and rehabilitation.”

Levick said, “The reason we’re giving them a chance to come out is to recognize their growth and maturity and their opportunity to reconcile with society. That’s what Henry is being denied.”

Pingback: Henry Montgomery Paved the Way for Other Juvenile Lifers to Go Free. Now 72, He May Never Get the Same Chance. – Freedom's Back

Pingback: Henry Montgomery Paved the Way for Other Juvenile Lifers to Go Free. Now 72, He May Never Get the Same Chance.

Pingback: Henry Montgomery Paved the Way for Other Juvenile Lifers to Go Free. Now 72, He May Never Get the Same Chance. – Curtis Ryals Reports

Pingback: Henry Montgomery Paved the Way for Other Juvenile Lifers to Go Free. Now 72, He May Never Get the Same Chance. | Patriots and Progressives

I am saddened by our US justice system. As a former youth minister visiting juveniles in jail, I can honestly say that most citizens have no idea how the system doesn’t work for rehabilitation and release. Prisons have become big business incarcerating low income, and minority citizens (mainly). That we as a “free country” cannot see to changing old laws that do not work for the current communities. Not to mention the vast amount of tax payer $$ used to keep those (who don’t belong) in prison there beyond a reasonable sentence.

This seems to be a fight that few want to enter into. It was exhausting visiting youth in jail when in most cases the parent was the one who needed to be held accountable ie.. kids running away from home due to violence in the home, drugs and alcohol abuse situations etc. I am encouraged, however, by the stories of those who are reaching out. Those who see education as a way to create a sense of hope, and there is hope! But it takes a village.

Pingback: [4/15/19] – ‘Juvenile Lifer’ at Center of U.S. Supreme Court Case Denied Parole Again