![]() Watch story videos below.

Watch story videos below.

JACKSON, Miss. — Cassio Batteast, a community advocate in Jackson, recently sat down with 20 of the students in the local school district who were causing the most trouble.

Over weekly meetings, they gradually opened up to him.

“I learned that 10 of the 20 had fathers who had been murdered or fathers who had murdered someone. Half,” he said.

“Not one of them,” Batteast continued, “ever received any counseling, any mental health treatment for that kind of trauma.”

Their experience also reinforced the need to carry a gun at all costs as a matter of survival.

“How are they going to listen to me when I tell them not to carry a gun? Then they say that their father would be alive today if he had a gun,” he said.

The aftershocks of gun violence on youth became apparent nationally in March when two survivors of the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, committed suicide.

[Related: Ex-juvenile offender finds key to stem youth crime: Give kids hope]

Sydney Aiello, 19, a 2018 graduate, shot and killed herself March 17.

Her mother said Aiello had post-traumatic stress syndrome from the mass shooting and was undergoing counseling.

A week later, 16-year-old Calvin Desir, another Parkland survivor, took his life.

Trauma and normalization

University of Mississippi

Dustin Sarver, an assistant professor in pediatric child development at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, says many youths are traumatized by gun violence, develop unhealthy coping patterns and don’t know how to communicate in a normal way.

Experts say gun violence can cause short-term and long-term psychological and social effects, especially in teenagers and adolescents. They say the more common gun violence becomes, the more difficult it becomes to treat.

“A lot of youths are traumatized by this gun violence. They become angry, there’s irritability and other unhealthy coping patterns that arise to deal with it,” said Dustin Sarver, an assistant professor in pediatric child development at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson.

“There’s also a normalizing process. That becomes one of the more difficult things to combat in counseling, just to know there are more healthy ways to relate to others. When you see violence and intimidation, that’s just how you solve problems. It doesn’t allow you to grow,” he said.

Individual efforts like those of Batteast are bolstering the more organized Credible Messenger and Cure Violence programs launched in Mississippi’s capital city, whose fundamental goal is to prevent gun violence from spreading by interrupting the cycle of violence.

Batteast works on both ends of what’s been called the school-to-prison pipeline, in the Jackson Public School District and in the Hinds County juvenile detention center, where he counsels at-risk youth. He estimates that close to 50% of those locked up in the Henley Young Juvenile Detention Center are referred from the school system.

He and Rukia Lumumba, who organized the Credible Messenger and Cure Violence programs, agree that more counseling programs and social workers are needed in both places to teach teenagers and adolescents how to communicate with one another and deprogram them from some of the lessons they learn on the street.

Justin Vicory

Cassio Batteast (right), a community advocate in Jackson, Miss., works in the Jackson Public School District and in the Hinds County juvenile detention center counseling at-risk youth in an effort to end the school-to-prison pipeline. He shares the same methods as Rukia Lumumba, who heads the Credible Messenger and Cure Violence programs.

“What many of these kids need are conflict resolution skills. For many it’s not taught at home. And that’s not the job of the teachers. They [teachers] already feel like they have to step in and fill that role. That’s one of the most important things we can do. They need someone they can talk to,” he said.

Nationwide, several initiatives aimed at promoting nonviolence have taken root in several areas that have become Ground Zero in the gun violence epidemic.

Gun deaths, youth and the South

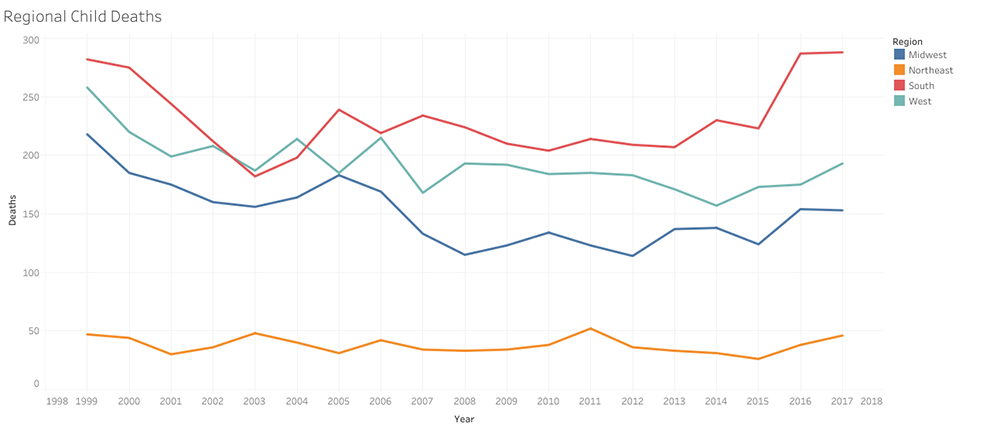

The South is one such Ground Zero. The region experiences more gun violence than any other part of the country, nearly doubling the national average of annual gun deaths.

The same is true of child firearm deaths, which went from 223 deaths in 2015 to 287 and 288 in 2016 and 2017, respectively, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The child firearm death rate is the lowest in the Northeast.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

.

Nationwide, since 1999, there have been 26,000 childhood gun fatalities. And each day, eight more children are killed by guns — through homicide, suicide or accident — amounting to 2,920 killed each year, while many thousands more are wounded.

While gun deaths in general gradually declined from 1999 to 2013, the rates of all gun deaths are beginning to trend upward.

The homicide rate for 15- to 19-year-olds from 2013 to 2016 has gradually increased from seven to nine deaths per 100,000, reaching 10 per 100,000 in 2016, CDC data shows.

Likewise, after declining from 11 per 100,000 in 1990 to seven per 100,000 in 2007, suicide rates for 15- to 19-year-olds are again increasing, reaching 10 per 100,000 in 2016.

The proportion of teens dying from firearms increased by nearly 30% from 2013 to 2016 — from 10 to 13 per 100,000.

Teenagers aged 15 to 19 bear the brunt of child firearm fatalities. They are most likely to die from homicide. African-American males make up the overwhelming number of the victims.

Fighting the epidemic

Scott Henggeler, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina, developed a preventative approach in dealing with youth and the effects of gun violence.

Called multisystemic therapy, it involves an intensive family- and community-based treatment designed to make positive changes in a variety of social systems, including the home, schools, community and among youth peer groups.

While it requires additional social workers, counselors and psychologists, it has been found to be cost effective in states that have tried it, such as Oregon, Sarver said. Other states, including South Carolina and Missouri, have seen decreases in recidivism, delinquency, arrests and incarcerations..

Inspire NOLA Charter Schools in New Orleans launched Project Live & Achieve in January to bring schools, community groups and faith organizations together to promote nonviolence, academic success, high expectations and community involvement.

The program was launched a year after two teens were killed Jan. 31, 2018, outside Edna Karr High School during a school basketball game.

Hands Without Guns, a public health and education campaign, works to change the attitudes of 12- to 18-year-old youth about gun possession. The program seeks to reduce the public acceptability of firearms by increasing youth anti-violence programs, many of them unconventional, such as theater groups, arts centers and video clubs.

For more information on Youth Gun Violence Prevention, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Youth Gun Violence Prevention

The program has three main components: an extensive media campaign, youth outreach and an evaluation process. The campaign has spread to Boston; Chicago; Michigan; Norfolk, Richmond and Virginia Beach, Va.; Washington, D.C., and Netherlands.

In Baltimore, the Living Classroom Foundation’s Fresh Start Program has provided juveniles 16 to 21 with employment training and academic remediation. Most are referred through the court system or by a probation or parole officer. About half have been convicted of a crime and are serving time at a juvenile lockdown facility. Typical students include juveniles charged with drug or gun-related offenses.

The program has seen success at curbing recidivism rates and helping participants get their GED and jobs.

Also in Maryland, the Prince George’s Hospital Center in partnership with the Washington, D.C., chapter of Concerned Black Men Inc. and the Prince George’s County School Board, developed the Shock Mentor Program. It shows at-risk high school students the aftermath of gun violence and other high-risk behaviors. Students are identified as at-risk by a teacher based on the student’s neighborhood environment, past experiences of violence in the student’s family or community or his or her association with peers in acts of violence.

The program corresponds with a larger conflict resolution course taught in the county’s high schools. The Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence developed the STAR curriculum (Stop, Think, Act, Reflect) in response to the escalating number of gun-related deaths of children and teens.

STAR is a prekindergarten through grade 12 program that educates students about the risks of handling guns and enables them to recognize situations that may lead to gun-related injuries, identify trusted adults, make safe choices, combat negative peer pressure and resolve conflicts nonviolently.

Just another day in Jackson, Miss.

These programs have hallmarks present in Lumumba’s Credible Messengers program in Jackson, where gun violence is pervasive. Last year, Mississippi’s capital city experienced 84 homicides, the most in more than 20 years. All but three were the result of gun violence.

About 80% of those homicides were interpersonal, or domestic disputes turned deadly, making their prevention by law enforcement just about impossible.

Mississippi state Sen. John Horhn has been sounding the alarm on gun violence and its effects on Jackson’s youth for years. He sponsored a bill to conduct a study that looked at the precursors to violent crime in the city.

The analysis, conducted by the Los Angeles-based BOTEC Analysis Corp., identified hot spots in the city where gun violence was most likely to occur. Researchers took a comprehensive approach, including as subjects every single Hinds County student in a 10-year period. And it focused heavily on the school-to-prison pipeline.

The 2016 study found a high correlation between those who failed a grade or dropped out of school and those who later engaged in criminal behavior.

Because of this, the Jackson Public Schools district sued the study authors for defamation, trying to prevent the study from being released. The district said the study makes “embarrassing and cruelly false assertions with no basis in fact.”

Later, the district dropped the lawsuit; the study can be found online. Caught up in the ouster of Superintendent Cedrick Gray and a near-state takeover of Jackson Public Schools, the study’s findings never were widely publicized.

Horhn is more optimistic about future data gathering. He said the CDC is making funding available to the Mississippi Department of Health to gather data on homicides, suicides, police interactions and accidents.

“It’s important data,” Horhn said. “It will give us a better perspective of violence as a health care issue.”

The stakes are dire.

“Some of these kids, they demonstrate all the classic signs of PTSD. They see so much violence and trauma in their daily lives that it’s almost impossible for it not to impact them in a negative way,” he said.

In the Credible Messenger and Cure Violence programs, messengers, mostly ex-offenders and former gang members, meet those likely to be involved in violence where they are: in homes, on the streets and even in the hospitals after they’ve been the latest victim of gun violence in the city.

The program is particularly effective on youth, especially those 16 to 22, who haven’t fully developed psychologically, Lumumba said.

“We look at crime stats, a lot of the violent activity is happening in that age group, mainly because as adolescents we make decisions based on impulse, based on rewards and benefits. We don’t have the capacity yet to make more rational decisions. It’s not based on long-term thinking,” Lumumba said.

‘How can I be part of the solution?’

The Credible Messenger program has inspired some in the community to pitch in where they can, such as Jackson resident Robert Davis.

Justin Vicory

Robert Davis, a community advocate in Jackson, Miss., and a former high-ranking gang leader, is negotiating with the city to lease the long-shuttered Medgar Evers Community Center in his neighborhood and turn it into a library and learning center where he and fellow Better Men Society members can mentor at-risk youth.

For the last 20 years, Davis had headed up the local chapter of the Better Men Society, a fellowship of Jackson men who step into the lives of Jackson youth who have no fathers or limited parental engagement.

Davis, himself a former high-ranking gang leader, is now in negotiations with the city to lease the Medgar Evers Community Center in his north Jackson neighborhood.

The building has been shut down for years. It once held a position of prestige in the community as a home away from home for many youth in the area.

Now, it sits vacant and is marred by chipped and cracked paint and overgrown shrubbery.

Davis wants to turn it into a library and learning center to stock with thousands of books. It would also be a community center where he and fellow Better Men Society members can mentor at-risk youth.

“I’ve been shot, stabbed, all that. Now, it’s about what can I do? How can I be part of the solution?” Davis said.

Tommie Mabry, an author and motivational speaker, grew up a few miles to the east. He, too, was once a victim of gun violence, having been shot in the foot. The injury cost him several basketball scholarship offers. He eventually secured another one after his foot healed.

He was also kicked out of seven elementary schools. He’ll soon have a Ph.D. in higher education from Jackson State University.

He stands in front of Rowan Middle School in north Jackson.

“I was kicked out of here, too,” he said. “But now I’m trying to raise the money to buy the building and the property all around it. I want to turn it into something the community can be proud of. That gets me up every morning. That dream.”

Law enforcement veteran Juan Cloy is also on board. Cloy, who is running for sheriff of Hinds County, says law enforcement needs a new approach. He was taught to use a hammer to tackle juvenile crime. Years later, he says, he had an epiphany.

The former hard-charging narcotics agent and gun instructor said he was moved by an experience he had with a youth with whom he had multiple run-ins.

The young man had a crack-addicted mother, Cloy said. His home had no running water, no food. The kid got in trouble at school because he didn’t have clean clothes to wear or the ability to bathe. He dropped out.

Cloy says he remembers stepping in to try and help. His wife, Ingrid Cloy, who works in the state’s foster care system, brought him clean clothes one day. They found him and about eight other teenagers standing on the street corner.

“We dropped off the clothes, but I imagined the scenario that would have played out if I had approached it the way my narcotics unit would have. We would have rolled up in an undercover unit. They would’ve ran. We would’ve found marijuana on them and we would’ve locked them up,” he said.

“But the reality is that most of these kids had no other place to go. They had nothing. So what were we accomplishing? I learned that we can’t outpolice the problem of juvenile crime. Something else is needed,” Cloy said.

Since then, the Cloys have adopted six children from troubled, inner-city neighborhoods. Some are still dealing with the trauma of gun violence, which has taken them years to talk about, he said.

“We have to have people who can serve as credible messengers who understand the conditions which lead to gun violence,” said Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, Rukia’s brother. “We have to find ways to engage and interact with our youth on a more consistent basis and love on them.”

“Whether or not you love those individuals who may be susceptible to instances of violence, we all must recognize that they paint the portrait of our city,” he said.

This story was produced in conjunction with the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting.

It is part of the JJIE’s project on targeting gun violence. Support is provided by The Kendeda Fund. The JJIE is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.