A police officer kneels down face to face with a child.

“I’m sorry I stole,” the child cries.

“It’s OK. Just don’t do it again,” the officer replies.

In another scene, a child looks upward to the officer.

“Thank you for saving our school,” the youngster says.

The pictures were drawn by Evelina Cheng, 12, of Sacramento, Calif.

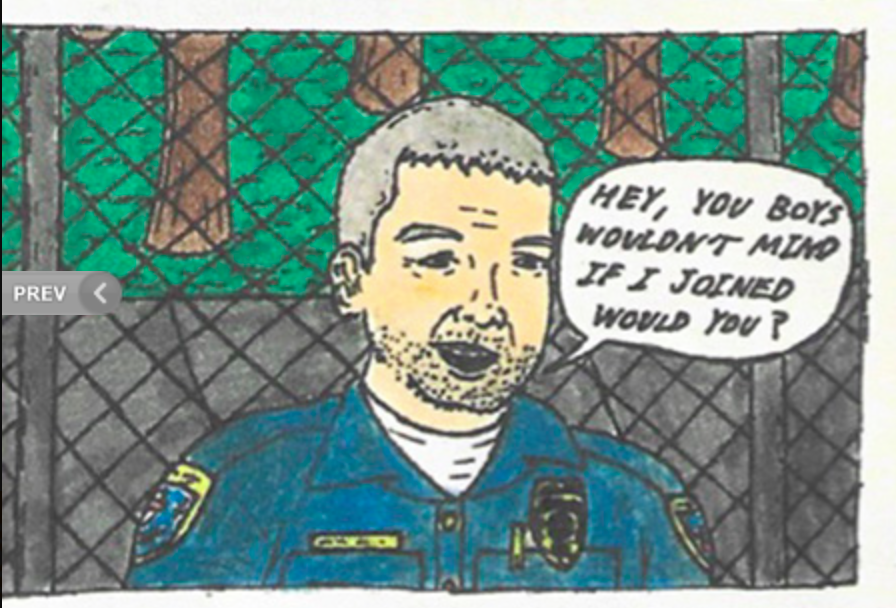

Kaleb J’bez Chew, an eighth grader from Baton Rouge, La., drew a comic strip showing a police officer playing basketball with boys who joke with him about his age.

These pieces of art tell us what young people want from police officers, said Lisa Thurau, executive director of Strategies for Youth, a nonprofit that trains police to improve their interactions with young people.

Her organization solicited the artwork in its first Youth Voices Contest, asking kids 12-18 to write or create a visual metaphor for how to improve police dealings with youth.

“Kids DO want interactions,” but they want to be given the benefit of the doubt, Thurau said. They don’t want police to assume they’re criminal because of where they live or the color of their skin, she said.

Alexie Boursiquot, age 13, urges police not to judge so quickly and kids not to run, in a poem entitled “No Need for Violence Here.”

Thurau said kids want officers to be familiar and to have interactions that are normal and that have nothing to do with crime.

“The call for that is very poignant,” she said.

But in so many cases, it’s not what kids are getting.

The contest entries in the 15-18 age category express sadness, frustration, fear and anxiety about how interactions escalate, Thurau said.

A drawing by Azaria Porter, 16, shows guns pointed at heads. “The past cannot be changed. The future is in your power,” the caption reads.

Kids fear they’re going to get killed, Thurau said. They may have never known anyone who was killed by police, but they’ve seen it on social media, she said.

For more information on Youth Gun Violence Prevention, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Youth Gun Violence Prevention

They also fear mass school shootings, an anxiety that didn’t exist before 1999, she and a colleague wrote in Education Week.

In the six months after the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, a flood of police officers entered schools across the country with very little training, Thurau wrote. Among the incidents reported, an 11-year-old was arrested for banging on a door and a 7-year-old was handcuffed because he wouldn’t stop crying, she wrote.

A 17-year-old Baltimore activist, Keyma Flight, submitted the winning entry in the Youth Voices Contest for her age category. Her essay included:

“It's not easy to wake up battling depression and anxiety at higher rates than it's ever been then coming to school where the biggest war is with the people who are supposed to stand for us.”

She expressed the heavy feeling of having to shoulder an adult burden:

“This generation is more earthquake than children. With all the identities being thrown at us, it's hard not to be 'unruly ‘ … We youth have to be peer and president in the same step.”

Her essay included a letter to an imaginary police officer she termed “Uncle Sam.”

“My teacher tells me to write to a police officer about today's youth. But for once, I'd like to see an officer writing, visiting, talking to the youth. Unfiltered and morals over code. I'd like to not feel like an activist for once. But a person.”

“There’s a general perception that there’s no way to fix what’s happening,” Thurau said.

Strategies for Youth trains police officers in 19 states, teaching them an approach that is developmentally appropriate and trauma informed, as well as racially equitable. Psychologists teach them about youth development and offer practical tips for working with teens. In addition, teen input helps police understand which interactions work best, as opposed to those leading to defiance and escalation.

“We wanted to understand and make more visible what we hear when we conduct assessments and interview youth,” Thurau said. The contest entries show what kids see “as a road map for improvement.”

“This is important to us because we have to understand how [youth] perceive the world if we as adults are going to be effective working with them,” she said.