NEW ORLEANS — Today, Judge Candice Bates-Anderson will likely take the bench in Orleans Parish Juvenile Court and sentence a chubby-cheeked 13-year-old boy to a term called “juvenile life,” which means he would remain in juvenile prison until he’s 21.

For more information on Youth Gun Violence Prevention, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Youth Gun Violence Prevention

In July, Bates-Anderson found Lynell Reynolds guilty of several charges, including attempted second-degree murder, for a March shooting that left another young man paralyzed from the waist down. The circumstances highlight the rate of gun violence that is still seven times the national average despite steep declines in recent years, according to the “Generational Gun Violence Reduction Plan” released last week by New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell.

In a rarity for juvenile court, a group of Lynell’s teachers plan to be in the courtroom, hoping for a different outcome. They say he was consistently a star student at ReNEW SciTech Academy despite having experienced an unimaginable amount of violence in his short life.

“I refuse to believe it’s too late to provide a 13-year-old with the professional help he needed the last decade of his life,” said Jess Bialecki, who taught him in kindergarten, the year that two older siblings were killed by a schizophrenic uncle while he was in the house. The following year, he and his remaining five siblings witnessed his mother’s death in their front driveway in a quadruple shooting that also left his father with traumatic brain injury.

After working closely with Lynell and the other Reynolds children, ReNEW social worker Carroll Bernard Feiling sought treatment for her own secondary trauma. “After working with that family so long, I had to get help,” she said. “So you can imagine the level of help that those kids needed, and in my opinion, did not get.”

‘Top 1% of trauma’

When Lynell’s parents did not agree to therapy for the children after his siblings were killed, Feiling — despite being the only social worker for a school with 700 students — devoted regular individual time to him, using play therapy, which helps young children work through the anger and anxiety that they often can’t verbalize.

Lynell’s experience stands out even in New Orleans’ hardest-hit neighborhoods, which have experienced high levels of violence for decades, said Dr. Denese Shervington, who is nationally known for her work with traumatized children. She assessed Lynell for his exposure to trauma, as she has assessed thousands of children. “I would say he’s in the top 1%. It’s pretty bad,” said Shervington, who is a clinical professor of psychiatry at Tulane University.

Shervington doesn’t want Lynell in voluntary treatment, but she also doesn’t believe he will thrive in a juvenile correctional facility. “I would advocate that he receive court-ordered treatment in a psychiatric facility; that’s where we are supposed to have kids like him, not in jail,” she said.

Teacher Riley Connick, who taught Lynell’s older sister, and has known the family for more than a decade, said that even during eighth grade, not an age known for public displays of affection, Reynolds would see her across the playground and holler her name. “He’d run over and give me a hug,” she said.

It’s that sort of affection that prompts Shervington to see potential in Lynell, largely because of the connections he had forged at ReNEW, which he attended from kindergarten through eighth grade. Thanks to cooperation between ReNEW staff and Lynell’s family members, he had a stability unusual for the city’s poorest families, who often move frequently and change schools with each move. Those strong bonds are important indicators for his future, Shervington said. Unlike other children in his position, who shut down and become distrustful of the world, “he had the capacity to respond to caring adults in his life,” she said.

Family neglect

His teachers note that juvenile justice systems themselves exist because research — and common sense — tells us that young people are both more impulsive and more amenable to rehabilitation. For instance, the mayor’s plan includes special programming for shooting victims 25 years old and younger, who are often caught up in the streets but “have a great willingness to change their behaviors.”

Even before the family shootings, it was clear that little Lynell and his siblings were neglected at home. “He would come to school in the same uniform clothes for many days in a row,” Bialecki said, who knew his clothes had not been washed because the stickers she’d given him for good work and citizenship days ago were still on his uniform, amid dirt and food stains. He often needed a bath and more sleep. Feiling and several teachers said the school made multiple reports to state child protection authorities, but nothing was done.

"These children needed help a long time ago,” said Wanda Solomon, Lynell’s paternal aunt, who took in the six Reynolds children and their badly injured father after their mother was killed. “I provided a roof over their heads and clothes on their backs, but they needed more emotional support than I could provide,” she said. “I have a big heart, but they have deep wounds that I couldn’t heal.”

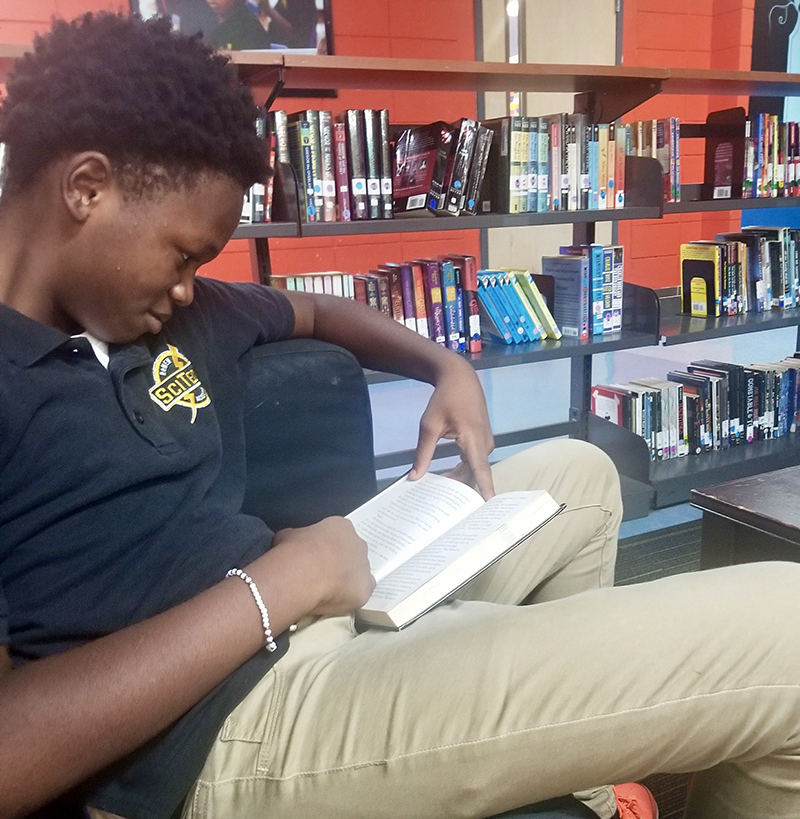

Teacher Angela Filardo, who taught Reynolds for three years starting in fifth grade, saw the effects of his trauma, when he began throwing up frequently and told her about trying to cut off his ear. “Though he’s very introspective, he had never considered that cutting off his ear would be a symptom of anxiety,” said Filardo, who took him to the school library or office with her during her planning period throughout his eighth-grade year. He would read books while she graded papers or made copies and the two of them would talk.

This spring, teacher and coach Alton Willis recalled Lynell correcting him about constitutional amendments. He had talked with his standout pupil about finding a new environment, maybe through a scholarship to a private Catholic school, with Willis chipping in for tuition. “He should be college-bound,” Willis said.

In a letter to the court, social worker Feiling outlined the chain of inaction that she saw. “If initial reports made to the Department of Children and Family Services in the fall of 2010 had been acted on, would I be hearing Lynell’s name on the news today?” she wrote. “What could have been done differently after Lynell’s first contact with juvenile court? These big questions highlight the systemic issues in our city that need to urgently be addressed. Schools cannot do this work alone. The system as a whole is failing our children. I’m just hoping it’s not too late for Lynell.”

Bialecki said that Lynell’s case shows that even children with promise can slip

through the cracks. “He’s the one who signifies that there’s something really really wrong with our system that we can’t do more for a kid with so much potential.”

[Related: Once a ‘badass Latina’ and handcuffed schoolboys, they now push for juvenile justice reform

Filardo notes that, even when he experienced bouts of homelessness or went through periods of severe anxiety, Lynell continued to do well in his studies. Even while he was detained at the city-run detention facility, Youth Study Center, he finished top in his class at Travis Hill School, where he gave a commencement speech, said Filardo, who received a letter from him, listing the six books he’d read.

In his letter, he also wrote about his hopes for himself, “I want that whole world; I’m waiting on God to lead me on the right path, because I can’t do it by myself.”

Update: The judge sentenced Lynell on Tuesday to “juvenile life,” the maximum sentence in Louisiana’s juvenile system — imprisonment in a juvenile facility until age 21. Bates-Anderson also gave him a chance for release before 21, if he earned his high school diploma, learned two trades, got the psychiatric treatment he needed and racked up minimal conduct violations.