Barbara Gauntt/Clarion Ledger

GREENWOOD, Miss. — Do not call Brittany Gray, Kenderick Cox and Marcellus Gray activists. The Greenwood natives prefer to be called who they are — members of the community. They also shy away from spotlighting their efforts to curb gun violence and gang culture in the city that they love.

However, their voices are vital in conversations that look to resolve the tribulations impacting the Mississippi Delta, which some believe is being consumed by an epidemic costing young lives. Who could be better at offering perspective than the people who live there?

“In the last several months, we’ve had about five gang-related shootings,” said Brittany Gray, 33, seated in her living room. One of the victims from Greenwood was a former student in a summer development program held at Mississippi Valley State University, where she served as an instructor.

“Brilliant student. Very talented. He didn’t make it through the program because of some gang activity, and he was incarcerated. He was 18 and had just applied back to the program this summer. He was looking for redemption, that second chance,” she said.

Registering people for the college admissions test and finding resources for individuals who want to relocate for various reasons are just small examples of her work.

Gray is all too familiar with gang culture. Fourteen of her cousins on her father’s side are current or former gang members. Although the names of the gangs are localized throughout the Delta, Marcellus Gray, Brittany’s cousin, agreed that they all fall under the hub of Vice Lords or Gangster Disciples in some form.

Photos by Charles A. Smith/Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

Brittany Gray describes herself as a community member and not an activist.

Marcellus, 42, grew up in the Bishop community of Greenwood, which he said was known for drug and gang activity.

“That’s how I was introduced to it. I was 13 years old,” said Marcellus of how he came to join the Gangster Disciples. “They were the family you didn’t have. The people who would be there for you when no one else would. I was being misled and didn’t know it.”

Marcellus graduated high school and spent time in college. However, he admitted, street life was something he could not shake. At 29, Marcellus was incarcerated for the first time. After doing a total of 10 years over two stints on drug convictions and a parole violation, he now spends his days working as a barber, detailing cars and hosting stop-the-violence rallies.

“In 2010, I lost my cousin by gun violence. Most of my family were in gangs. After he was killed, I ended up going back to prison,” he said. “While I was in prison, a lot of my close friends died the same way. I could see the cycle.”

[Related: Dixie Pipeline: Guns Bought in Mississippi Often Reach Chicago Streets]

[Related: Scarred By Chicago Gun Violence, Student Finds Refuge, Purpose in Mississippi]

Having two daughters (8 months and 20 months) also serves as motivation, Marcellus said. “I looked at the violence in our community, and I knew I did not want my kids raised in this,” he said. “It’s also my duty because I can’t just sit back and watch the same kids I’ve known since babies throw their life away.”

How to ‘save ourselves’

It’s a glaring fact that perpetrators and victims of gun and gang violence have grown increasingly younger. And the seemingly unanswered question is “Where are they getting the guns?”

“That’s the scary part,” said Brittany, who is pursuing her doctoral degree in public policy at Mississippi State University after getting a degree at Brooklyn College. “Our local mayor, our council members, this isn’t an issue for them. Their kids are safe. They’re not attending funerals. They’re not addressing anything.”

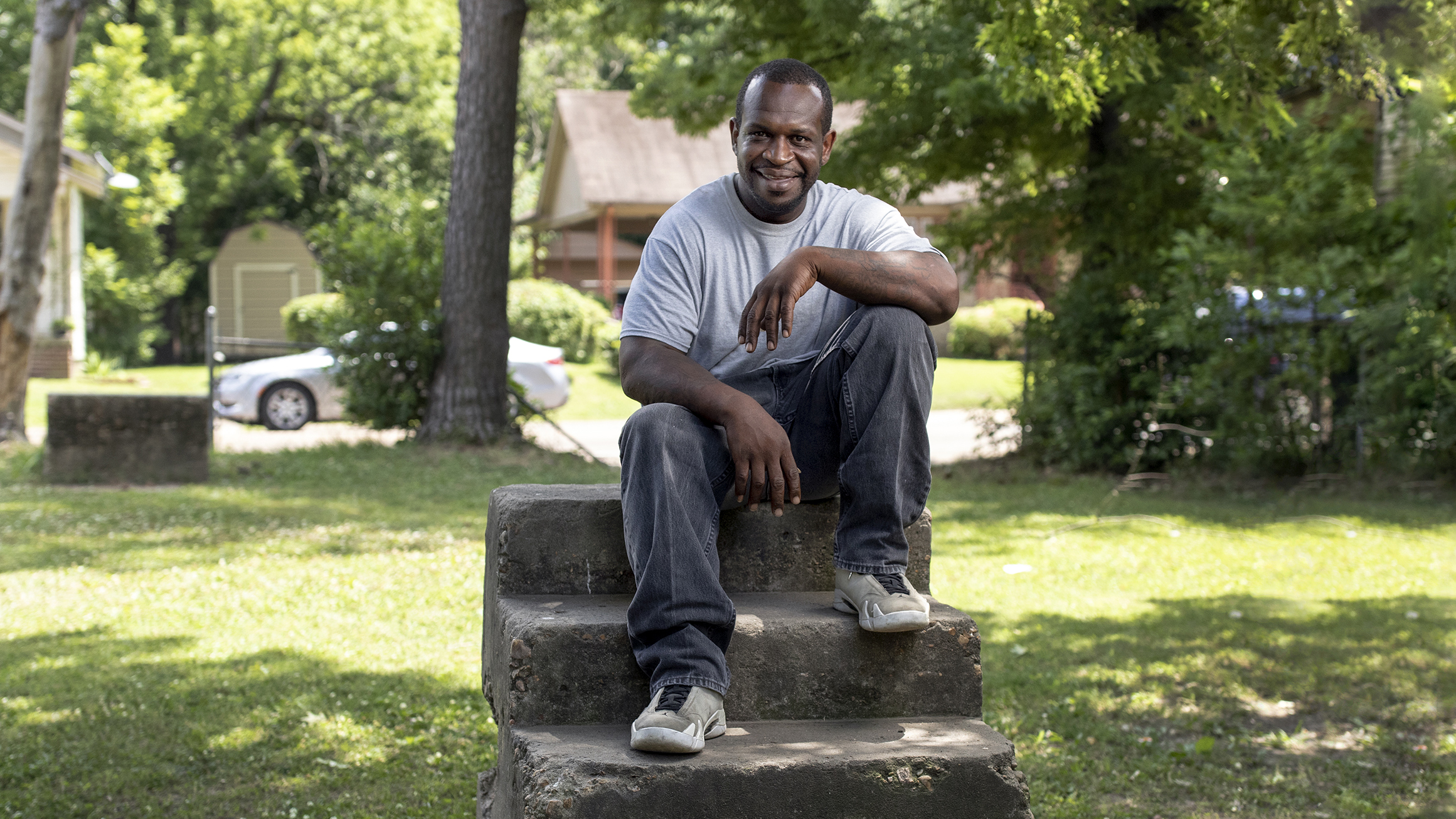

Marcellus Gray, 42, a local barber in Greenwood, Miss., is all too familiar with gun culture. He works to help kids shy away from street life.

Confirming that there have been several gang-related shootings in Greenwood over the last several months, Police Chief Ray Moore says he follows a standard playbook. He said the department works closely with informants to prevent potential conflicts from arising by beefing up police presence. But he acknowledges it’s hard to verify the department’s success.

Reaching out to local governance is not something Brittany Gray advocates. She implies that the answers are within. “We’re at the point now where we’re going to have to save ourselves.”

There is not exactly a manual on how to “save ourselves.” Addressing socioeconomic disparities, gun accessibility and parent accountability are some factors the community members suggest need the most attention.

Brittany Gray has helped organize political campaigns for the likes of Barack Obama and the late Chokwe Lumumba, who was elected mayor of Jackson in 2013 and unexpectedly died in 2014..

She admits to not finding cursory endeavors to end gun violence appealing. Opting for a more holistic approach, Gray said she would rather determine the root cause of the issues and prioritize intentional conversations over motivational speakers and people who are not directly impacted attending rallies.

“They’re not the ones holding the guns. They’re not the ones being threatened. They’re not the ones that are fending for themselves. As a result, folks can’t really reach that population and having event after event after event is not the most beneficial,” she said.

For Cox, 35, an older cousin kept him from indulging in the “lifestyle.” If not, the educator might have easily been detoured from the path that led him to Delta State University, where he earned a bachelor’s in health education and physical education. He also received a master’s degree in administration and supervision from the University of Phoenix.

“He told me, ‘You’re one of the smartest kids in the family. You’re going to be a doctor or lawyer. This isn’t for you,’” recalled the reserved Cox. The same cousin was later killed.

Kenderick Cox, an educator, discusses an organization he created in 2011 and relaunched in 2017 called Here We Stand. It helps 8- to 18-year-old black males navigate adolescence safely and away from gun violence.

“I always talk about the blueprint. There is a blueprint for everything. In the streets, we know the blueprint for how to make money. If you sell this amount of [drugs], you make this amount of money,” he said. “The same young man thinking about getting in the lifestyle may want to be a plumber, electrician or a doctor. Nobody is pulling him under their wing and saying, ‘I’m going to show you how to make legit money.’”

The blueprint Cox is using to keep youth on a productive track is Here We Stand, a community outreach organization for young males 8-18 that he founded in 2011 and relaunched in 2017. The yearlong program services about 65 kids during the academic year and an average of 25 during the summer.

When a participant reaches their junior year in high school, he becomes a mentor for others. The five-man mentoring program is called “He ain’t heavy. He’s my brother.” Cox said the name acts as a reminder “to always have each other’s back even when one is struggling.”

Mentors teach participants life skills like how to change a tire and how to prepare for a job interview. Youth also do job shadowing of various trades so they can see that they can have fruitful lives without having to get higher education. The organization also created a community garden where Cox said they spend hours gardening and planting vegetables.

Although the young men may be considered low-performing students by school standards, Cox is undeterred.

“Some people ask me why these kids,” he said. “Because these are the kids who are going to be here. I want to show them that they have other options to be successful.”

This story was produced in conjunction with the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange and published with the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and the Clarion Ledger. It is part of the JJIE’s project on targeting gun violence. Support is provided by The Kendeda Fund. The JJIE is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.