WASHINGTON — When photographer Richard Ross turns his lens on America, he sees a country that incarcerates 12-year-old children. He sees youth in prison — even though they themselves are victims of abuse and trauma. And he sees “juvie lifers” who spend decades behind bars for crimes they committed before their brains were fully developed.

He sees, in other words, a society that holds children — especially those of color — accountable to institutions rather than the other way around. And he’s using his camera to show what that distorted view looks like from inside the prison walls in the hopes of one day changing it for the better.

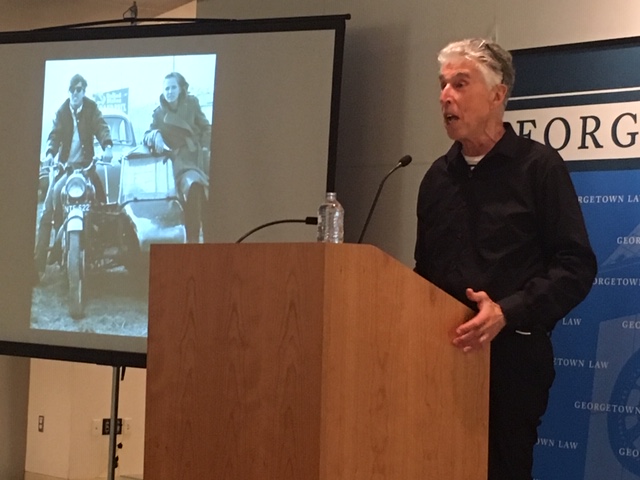

“What happens if you flip that around and hold society and its institutions accountable to the child?” Ross asked Monday at a presentation at Georgetown University Law School. It was the first of several events this week sponsored by the Georgetown Juvenile Justice Initiative to mark Youth Justice Action Month.

Art, he said, has the power to make social change — sometimes more than other social movement tools, like data and statistics. “Images are witness to what’s going on,” he said. “Images are not fake news.”

A professor of art in Santa Barbara, Calif., Ross has produced numerous books, including a series on the placement and treatment of U.S. youth in prisons and detention facilities. He is the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Annie E. Casey and Macarthur foundations, and of fellowships from the Fulbright Commission and Guggenheim Foundation.

His work has been featured in museums, universities, major media outlets and even in the halls of Congress.

In addition to a lecture, Ross’ presentation featured roughly two dozen images of youth in the justice system. In muted blues and greys punctuated by flashes of red and orange, the images depicted teens in one-room cells with metal cots and toilets and peeling paint, beds in solitary confinement rooms with no natural windows and groups of youth dressed in orange jumpsuits against stark white walls and sterile lighting.

“I realized I was the conduit for these voices,” he said of his decision 15 years ago to pursue what has since become a longitudinal photographic study of the U.S. juvenile justice system. Since then, he says he has become “an advocate’s advocate” — an activist-artist who seeks social change.

“One of my goals is to be sufficiently dangerous,” Ross said. “I want to make beautiful trouble.”

And he is succeeding, according to Michael Blackson, 17, a senior at Thurgood Marshall Academy, a public charter high school in Washington. “I was shocked and in awe,” he said after the presentation. The images were “relatable,” he said. “I could feel a sense of connection to family and friends who were incarcerated.”

Chrissy Jackson, 17, a youth organizer at Black Swan Academy, an organization that supports black youth leadership, agreed. The presentation, she said, was shocking.

The work is both rewarding and punishing, Ross said, often involving long hours interviewing and photographing young people in prison facilities many miles from his home, followed by late nights in cheap motels transcribing interviews. But at 72, he says he can’t stop — and won’t stop — as long as juvenile injustice exists.

Keep up the great work Richard!

Are we now looking to excuse youth who commit serious crimes like rape and murder because the brain isn’t fully developed and/or because the youth suffered abuse and trauma?

I don’t think they need to be excused for the crime.but the harsh time of punishment for life needs to be addressed.Their brains aren’t fully developed and don’t understand the reality and consequences of their actions.they made a bad choice and trust me they are paying for it for the rest of their life.Theres no second chances one bad choice and that’s it.no chance for redemption