In the early 2000s I had the privilege to serve as the administrator of the Pinellas and Pasco counties Juvenile Assessment Centers. For those of you not familiar with the JACs, their purpose is to serve as a one-stop shop for all juvenile services. The JACs provide law enforcement with a central point of contact for juveniles who have been arrested.

Vinnie Giordano

While serving as the administrator I had the pleasure of working with both human service agencies and law enforcement in the ongoing effort to help reduce the rate of arrests for juveniles. Of particular concern was the rate at which African American children are arrested and brought into the criminal justice system as compared to their Caucasian peers.

For more information on Racial-Ethnic Fairness, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Racial-Ethnic Fairness

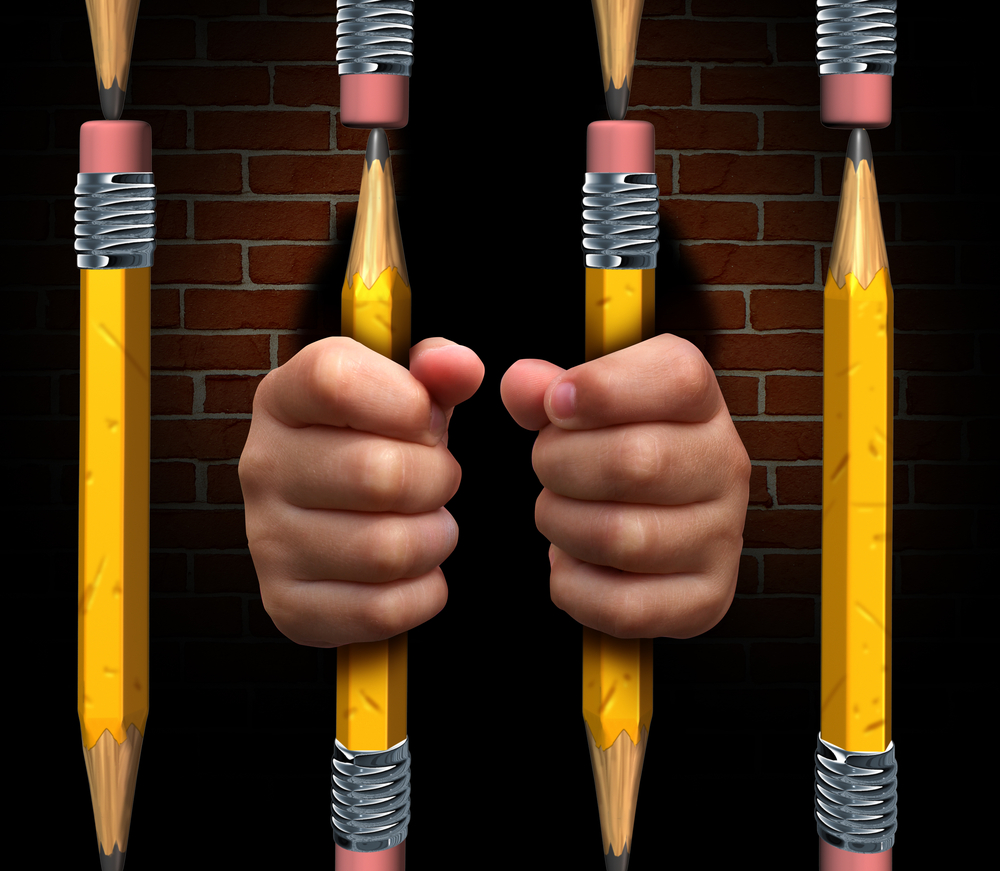

Beginning in the mid-2000s, organizations such as the NAACP were highly concerned about the rate of arrest of African American children, especially young men, for minor offenses, especially in the schools. The catchphrase school-to-prison pipeline became part of the common vernacular in the justice system. Professionals such as myself saw a disturbing trend where African American children had a higher rate of arrest and incarceration, while Caucasian children were often provided with treatment.

During my tenure as the JAC administrator, the NAACP targeted the imbalance that existed in school-related arrests and referrals to the criminal justice system. At the time a common charge in Pinellas County that was levied against children of all groups was called “disruption of a school environment.”

School-to-prison pipeline

For those not familiar with this crime, disruption of a school environment took behavior such as disrespect out of the hands of the teacher and the administrator and instead put the ability to discipline into the hands of the criminal justice system. Unfortunately, many young African American children were removed from the classroom and placed in the juvenile justice system. So the goal of the NAACP was to reduce or eliminate this charge, thereby significantly reducing the school-to-prison pipeline. Eventually the disruption of a school environment charge went from being one of the number one reasons for referral to the Pinellas JAC to virtually vanishing overnight.

In 2013, the Broward County School District and the NAACP entered into what was called “a groundbreaking collaborative agreement on school discipline.” In this attempt to reduce the school-to-prison pipeline, the Broward County School District, law enforcement and community partners entered into an agreement where the schools would utilize “common sense approaches such as counseling and mentorship,” and limit school referrals and arrests, especially for African American children. So the question to now examine is if such efforts have made an impact in reducing the number of African American children entering the criminal justice system.

According to the data collected by the state Department of Juvenile Justice’s Disproportionate Minority Contact/ Racial Ethnicity Disparity Benchmark Report for 2017-18, it would appear that efforts to reduce criminal justice contact for African American children has failed across Florida. According to the report, African American children make up 21% of the juvenile population (ages 10-17), while Caucasian children make up 43.8% of Florida juvenile population. Controlling for population size, we should then see a reflective rate of arrest and incarceration according to the current racial makeup. However, there is a significant imbalance present still to this day, as evidenced by the current criminal justice numbers provided by the Department of Juvenile Justice.

2017-18 Data

| Black | White | |

| Arrests | 50.9% | 33.8% |

| Adjudications | 54.2% | 31.1% |

| Diversion | 41.2% | 41.9% |

| Residential Commitment | 60.6% | 27.1% |

| Transfer to Adult Court | 66% | 20.7% |

| Secure Detention | 58.4% | 26.8% |

The next question that needs to be examined is whether the number of African American youth in the juvenile justice system has been impacted significantly since conscious attempts have been made to reduce arrests.

Sadly, the numbers do not look as promising as they should, according to the state Department of Juvenile Justice. From 2013 to 2014, the number of African American children arrested in Florida was 38,866, and by 2017-18, that number was down to 30,297. While this is good, it is not as significant as it should be. Detention data is also a mixed bag, with detentions at 8,765 in 2013-14, but finishing at 9,315 by 2017-18. One bit of good news seems to be a more significant decrease in referrals to the adult system, with a high point in 2015-16 at 1,146, but a low of 771 by 2017-18.

Despite some changes in the rate of arrest and incarceration for African American children, it has become apparent that the current efforts are falling way short of creating equity in the treatment of African American children as opposed to Caucasian children. Because of this, new aggressive practices must be implemented in order to establish fairness and equality in the treatment of youth in Florida.

The state needs to work toward accomplishing long-term effective changes, such as the end of zero tolerance practices and to train all education staff to balance school discipline practices to ensure a fair and equal balance in the treatment of minority youth. According to the Washington Post, African American students faced greater rates of suspension, expulsion and arrest as compared to their Caucasian peers. In 2014, the Obama administration recommended the elimination of zero tolerance policies that often further the school-to-prison pipeline.

This is especially important in schools, as Florida should be looking to move away from over-relying on school resource officers to serve as disciplinarians. Police should play an important role in the lives of kids, but not a central role as the main arbitrator of punishment. Shifting zero tolerance out of the schools will instead place the role of discipline back on school administration so law enforcement can be left to focus on more important aspects of their job.

Remedies

The use of diversion for misdemeanor and lesser felonies can be extremely effective at reducing future criminal behavior and thereby reduce or eliminate the school-to-prison pipeline. By diverting African American youth away from the criminal justice system when they do violate the law, this will allow human service, mental health and social workers to address behavioral issues. Furthermore, diversion allows youth to give back to the community through community service hours and steers them away from the criminal justice system by keeping them out of a detention facility.

The Obama administration also recommended that schools should implement regular training with all school personnel so they can utilize strategies for addressing behavior effectively and fairly. These trainings must be implemented across the board in Florida and be based on evidence-based practices. Unfortunately, past popular efforts to reduce criminal behavior have often been based more on gut assumptions than actual research. So any training program needs to be based on scientific research and not intuition to be effective. These trainings should focus on the specific needs and issues that young African American children face while also working to eliminate potential issues of bias.

Finally, all records — with the exception of extremely violent cases — should be permanently sealed and possibly expunged. By doing this, those children who have not been eligible for diversion might still have an opportunity to start their adult life with a clean slate. This would eliminate the harm of having a criminal record for African American youth by removing barriers to employment, college and even military service.

Since the early 2000s, the state of Florida, along with several groups such as the NAACP, have been concerned with ending the school-to-prison pipeline for African American children. Since the implementation of some efforts, it appears that the goal of reducing the number of African American kids getting arrested in Florida has failed significantly. In looking at the arrest and referral data, one can see that African American children still face harsher penalties than their Caucasian peers.

The time has come for serious changes to our methods of dealing with African American youth. Florida needs to spend considerably more time and resources to eliminate the over-reliance of the criminal justice system to address the issues facing African American children. If Florida fails to do this, the state will continue to see increased numbers of African Americans moving from the school system into the prison system.

Vinnie Giordano, Ph.D., is the former administrator of the Juvenile Assessment Center in Pinellas County, Fla. He is now a graduate professor of human services at Ashford University and a graduate professor of criminal justice at Averett University.

Why does immigrants get vaccinate before African American Florida is really predjidus governor no good