MONROE, Wash. — Inevitable. That’s how winding up in prison felt for a group of former foster youth — now adults who are imprisoned at Monroe Correctional Complex in Washington state.

The men, who are part of the prison’s “state-raised working group,” convened a half-day conference last week to explore how to sever the pipeline they say delivers too many from foster care to prison.

The state, as the de facto parent of foster children, must do a better job protecting, nurturing and educating their children, the men told the nearly 80 attendees, who included leadership from the state’s child welfare and juvenile justice agencies.

“What are these young people’s lives worth to society?” asked Ray, one of the 22 state-raised men who shared their stories and facilitated group discussions in the prison’s cavernous chapel. “And what’s the cost to society if we neglect to invest [in these youth]?”

For Ray and the others, their trajectories began with childhood abuse or neglect that brought Child Protective Services to the door. At least one was born in prison. Most cycled between foster homes, group homes, homelessness and juvenile detention — where several said they experienced further abuse.

Few got an education beyond the eighth grade. Many aged out of foster care at 18 with no job skills or support system, though often with a lengthy rap sheet.

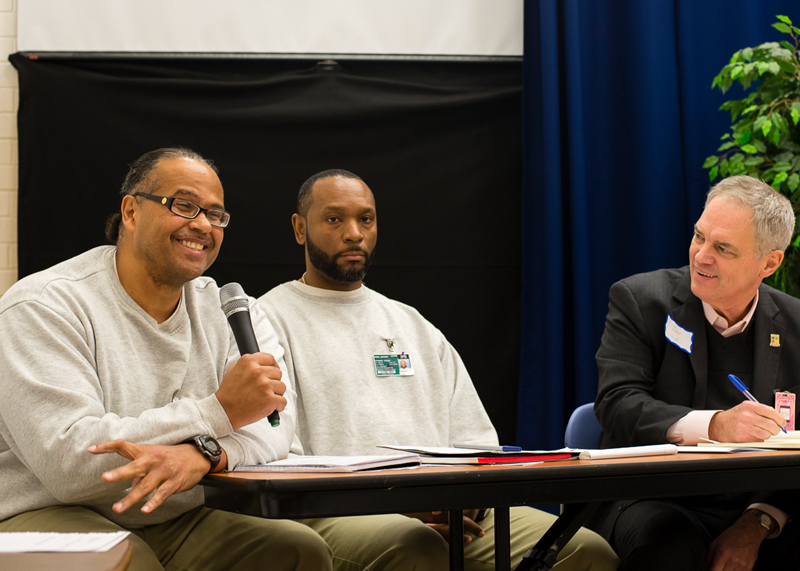

Allegra Abramo

Percy Levy (left), who was born in prison and aged out of foster care, speaks about the importance of children's first interaction with a social worker as part of a panel discussion on preventing the foster-care-to-prison pipeline, as Jeff Fox (center), and Department of Children, Youth and Families Secretary Ross Hunter (right) listen.

Along the way, they became inured to the experience of incarceration and learned to distrust adults, they said.

“Where the hell else were these kids going to end up?” said Nick Hacheney, of Monroe’s Concerned Lifers Organization, of which the state-raised group is an offshoot. “Unless there was some miraculous intervention, they were going to end up right here in prison.”

Dual status

Many young people incarcerated in the state’s juvenile rehabilitation facilities, which house those facing longer sentences for serious or repeated crimes, are already well along the pathway from foster care to prison.

About 40% have experienced foster care, said Marybeth Queral, assistant secretary for juvenile rehabilitation, which merged with the Department of Children, Youth and Families this July. Nearly 80% of all youth in the facilities had been the subject of abuse or neglect investigations. The number of adults in state prisons who experienced foster care is not available.

“The child-welfare-to-prison pipeline is alive and well,” Queral said during a breakout discussion.

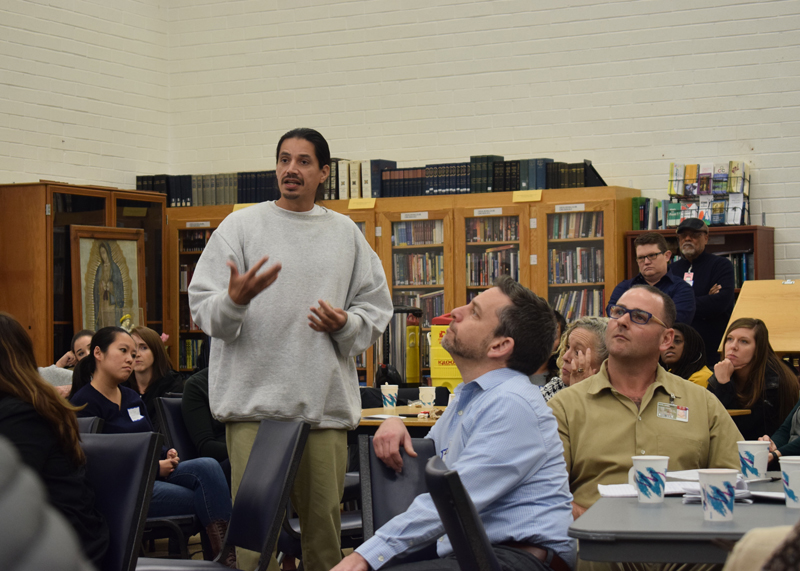

Jesse Colman/Treehouse

Carlos Heureca, a member of the "state-raised" group at Monroe Correctional Complex, suggests that group homes provide mentors who have "been there and done that" during a panel discussion on ending the foster-care-to-prison pipeline.

She noted some positive steps, such as a state law passed last year that reduces the number of crimes for which juveniles can be charged as adults and allows them to stay in juvenile facilities until age 25. But funding and staffing shortages are a barrier to providing the services these youth need, she said.

Education in juvenile rehabilitation is particularly under-resourced, DCYF Secretary Ross Hunter told the crowd during a panel discussion.

“The language I would use ... is constitutionally inadequate,” Hunter said. The per-child funding in institutional schools is significantly less than in regular schools, he said, despite the high needs of many detained youths, half of whom qualify for special education.

“It’s terrifying to me that we have this system, and we expect kids to come out of juvenile rehab and launch themselves back into the normal public education system,” Hunter said.

Inadequate education, mentoring

State-raised group member Ray said he was sent to adult prison at 17 and released three years later to a homeless shelter, still with just a sixth-grade education. (The Department of Corrections requested that only first names be used for some of the men due to “victim concerns.”)

Incarcerated foster youth in their late teens and early 20s “are still children,” often with unmet educational needs, said Ray, now 39 and working toward an associate’s degree.

“I would like to see state-raised youth have special funding set aside for their post-secondary educational needs,” he said, “so they can get out and be the contributing members of society that I know they can be.”

Foster youth coming out of public schools often don’t fare much better. In Washington state, less than half graduate from high school in five years, said Dawn Rains, chief policy officer for Treehouse, which has significantly boosted graduation rates among foster youth by providing them with mentors.

Allegra Abramo

Washington State Department of Children, Youth and Families Secretary Ross Hunter (left) speaks with retired King County Juvenile Court Judge Wesley Saint Clair.

Having the sort of consistent, reliable adult in their lives that Treehouse provides is critical for foster youth, a number of the men noted. Instead, most foster kids endure constant churning of homes, case workers and schools.

Some said they didn’t get the mentoring they craved until they landed in prison.

“When we were in foster care, we felt that we were alone,” said Faraji Blakeney, one of the incarcerated men. “And when we came together and were allowed to be vulnerable and share our experiences, we found we weren’t alone.

“But why did it take prison for us to find out that we’re not alone?”

The state-raised group launched four years ago under the aegis of the Concerned Lifers Organization, which has operated at Monroe for about 45 years.

Hunter, who has met previously with the men, said that their insights have “changed how we do stuff in juvenile rehabilitation.”

For example, he said, the department is working to ensure that youths who will be released from detention into foster care can build relationships with the people they will live with afterwards.

“I just love how thoughtful these guys are,” Hunter said.

In the long run, he told the crowd, he wants to lower the number of children in foster care from the current 9,000 and shorten the time they are there.

“If we remove fewer children, we’ll need fewer foster parents,” Hunter said, alluding to the state’s ongoing shortage of foster families. “And perhaps we can be more selective” about who gets licensed to foster.

‘Institutional racism’

We also need to address another “elephant in the room,” retired Judge Wesley Saint Clair, who presided over King County Juvenile Court until March, said in an interview after the event. “And that’s the prevalence of how institutional racism affects our various systems, whether it's child welfare, schools or courts."

Black and brown children are overrepresented in foster care and linger there longer, Saint Clair said. In the courts, they are often sanctioned more harshly, and in schools they are the first to be kicked out, he said.

“And as long as we’re not willing to address the biases,” he said, “it’s going to be a continuing, everlasting conversation.”

For youths who received life sentences when their adolescent brains were still developing, Saint Clair added, the courts have decided that they need to be able to revisit those sentences.

That’s exactly what the state-raised group would like to see happen for people who entered prison before age 25 and have already served decades.

“Let’s take a look at this individual, and see if it's just that we keep this person in prison for the rest of their life, when ... the state was involved in how they got to where they are,” Hacheney said.

“They deserve a review process,” he said, “they deserve a different ending to their story.”

This story has been updated.