(Part 3 of 3)

BRADENTON, Fla. — While most Florida Commission on Offender Review decisions are made during hearings without the inmate present, parolees whose supervision terms are being reviewed sometimes do show up in person.

Five of the 33 cases being considered during a hearing on Oct. 9 related to inmates who were already out on parole. Parole in Florida is considered an act of grace by the state, not a right. According to state rules, parolees are not allowed to possess firearms or ammunition, use drugs or alcohol, or even “enter any business establishment whose primary purpose is the sale/consumption of alcoholic beverages.”

Every two years, a parolee will have a “parole supervision review,” which means FCOR may decide to either loosen or tighten the terms of parole — or even return a parolee to prison.

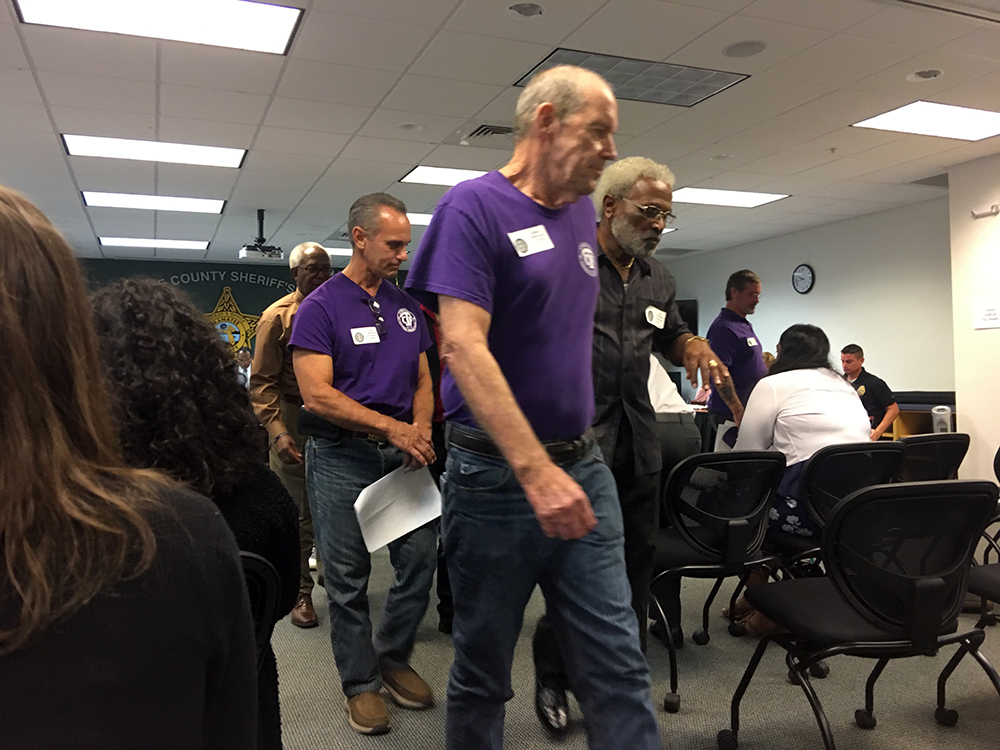

On this day, the commissioners called the case of Donald Freeman, who was sentenced to life in 1982 for robbery with a deadly weapon, and paroled in August 2017. Supporting him in the audience were about a dozen men in purple T-shirts with the words “Free to Serve” printed on the back. They had come through the Corrections Transition Program, a two-year program that teaches inmates at Everglades Correctional Institution how to function in society when released. Freeman was living in a halfway house and learning plumbing at a technical college.

Freeman thanked the commission for giving him the “opportunity to be the man I should have always been. Not a day goes by that I am not remorseful for my crime and my victims. I wish I could turn back the hands of time, but I can’t.”

One by one, Freeman’s fellow parolees stood to face the three commissioners on a dais, and described him as a hard-working, humble man. “He makes a collection for the guys in prison he left behind” so they can buy necessities from the commissary like deodorant or soup, one said. Another said he hadn’t had a penny to his name when released from prison, but Freeman had generously loaned him $100. Said Freeman’s roommate: “He has a credit rating over 700! I mean, that says a lot. He’s worked his butt off whole time he’s been there.”

[Part 1: 3 on Florida Commission Decide Parole of Thousands of Inmates]

[Part 2: Medical Release Is Decided By Florida Commission That Doesn’t Meet Such Inmates]

Freeman said the terms of his parole required him to attend mandatory Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings; he asked that those be dropped because he was exhausted. “I be so tired. I go to school. I work. Last night, I got two hours of sleep.”

“He has no drinking problem or drug problem,” one of his friends announced.

“He has a sleeping problem,” Commissioner David Wyant quipped.

“I ain’t never worked in my life! So I’m learning!” Freeman said with a chuckle.

Wyant voted to eliminate the meeting requirement and move Freeman to quarterly reporting. He set the case to be reviewed again in June 2021.

Commissioner Richard Davison said, “It looks like you’re doing everything that’s expected of you and a little more. I hope you’re not the driver today.”

“No, sir,” Freeman said, as the audience laughed. He said he’d bought a car but failed his driving test and would have to retake it.

Davison agreed with Wyant to reduce the supervision and delete the meeting requirements. He told Freeman to keep moving in a positive direction, “and we look forward to seeing you in two years.”

With that, Freeman retreated to the audience, where his friends swamped him with back-slaps and hugs.

A split decision

After the three commissioners (Melinda Coonrod is the third) discussed a few cases where the parolee did not appear, Melvee Tucker sat before them. Tucker, tall, with a shaved head and athletic build, looked younger than his 62 years. He had been convicted of murdering a convenience store worker during a robbery in 1974, when he was 17. He was released on parole in 2003. He was hoping the terms of his supervision would now be loosened.

“When I look at the left of the 62 [on a timeline], and look at the right, I don’t have as many years going to the right as the left.” he said. “I’m remorseful. I’m all about accountability and responsibility. Prison is a great big think tank because all I did was think about my past, present and future. I don’t have as many years to go to the right as I did to the left.”

He was reporting to a parole officer quarterly, but asked for “a little more leeway. Even though parole is not a right, it’s an act of grace and mercy. I know I’m not entitled to anything.”

Davison noticed that for 14 of the 16 years he had been out on parole, Tucker had to report for supervision monthly, which he said was a long time for such strict oversight.

Tucker said he’d been unaware he could get it reduced, and was busy working. He said he had worked as a counselor with Miami-Dade police. He thought that should have been enough to prove he was a responsible citizen. “I’m quite sure that would have been ‘Abracadaba!’ and I would have been off parole.”

“There is no ‘Abracadabra,’” said Davison, leading the audience to chuckle.

The commissioners noticed that Tucker was behind on restitution payments and that warrants had been issued for his arrest in 2011 and 2013. Tucker explained that in 2011, he’d been arrested for drug possession, but a parole officer referred him to a yearlong drug program, which he completed, and that in 2013 he was arrested after arguing with a niece, but charges were dropped.

Davison mulled his decision. He acknowledged that the commission often made its decision based on reports without ever meeting the people whose fates they were deciding. He said it was “equally as important to the whole process” to meet them. Wyant agreed: “Hearing from you probably helped your cause here today.”

Wyant said he had concerns about the “2011 and 2013 bumps in the road” but given that Tucker had gone into prison at a young age, spent most of his adult life there and been on supervision so long, “I’m in a position to terminate your supervision today.”

“Mr. Tucker, I’m not there,” countered Davison. “I go back to why we’re even here. And that’s based upon your conviction for first-degree murder.” He voted to “advance the ball a little bit” and reduce Tucker’s supervision from quarterly to semi-annual reporting.

Typically, decisions about parole supervision are made by a panel of the two commissioners. Because there was a split vote, Coonrood, chair of the commission, would break the tie.

“You did have some bumps along the way,” she told Tucker, “but it has been a number of years since your substance abuse issue and I haven’t seen anything in the record indicating this is a problem now. It’s been eight years. You also had another bump in the road six years ago. It appears you’re doing everything you’re supposed to, and you’ve been on supervision long 2enough that I think you’ll continue to do the right thing. So I’m going to agree with commissioner Wyant and terminate your supervision.”

Applause broke out in the room, and the hearing adjourned.

This project was collaboratively produced with Jaxlookout and underwritten in part by The Vital Projects Fund.