NEW YORK — Chloe Rodriguez gazes down the sidewalk on East 150th Street. It’s dusk and she has shed her school uniform for a black hoodie. Her night shift, as a receptionist at the clergy office in Immaculate Conception Church in the Bronx, starts in 15 minutes.

She stops and holds her breath for a second. The church is around the corner. Rodriguez, 16, makes a fist around her keychain, one key sticking up through her fingers. Sharp. She walks quickly.

Across the street, she sees bodies. Lots of them. Some look like lumps under blankets. Some are more visible. Men with needles sticking out of their arms lie propped up against an abandoned cinderblock building behind the Cookies Dept. Store. The smell of feces lingers in the air.

Drug users sleeping in broad daylight on East 150th Street in the Hub.

Rodriguez lives in a South Bronx neighborhood called the Hub, concentrated around the intersection of East 149th Street and Third Avenue. She calls it “the Hub of Heroin.” The neighborhood has the highest number of overdoses in the city, according to the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOH).

The South Bronx’s opioid crisis got a lot of coverage after the New York Daily News began spotlighting the neighborhood in May 2017. But a small grassroots movement led by children has largely flown under the radar.

Needles can be found almost everywhere in the Hub — named for the five-way intersection at East 149th Street and Third Avenue in New York City’s South Bronx.

Along with a growing number of young people, Rodriguez belongs to a committee called Take Back the Hub. The group, made up of about 30 people, picks up needles and organizes weekly protests to bring attention to the heroin running rampant in the community. Young people under 16 make up over half the group.

“The young people, they're our voice,” said Take Back the Hub founder Marty Rogers, 67. “Their message is, ‘We are tired of you adults. We are sick of you cowards, who have allowed this to come and invade our community.’”

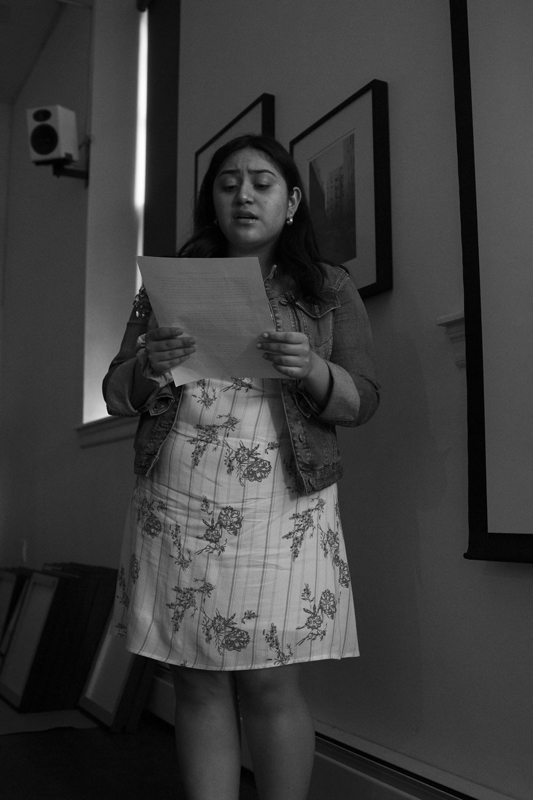

Chloe Rodriguez, 16, a photography student at the Bronx Documentary Center, displays a print of her work on the neighborhood’s heroin epidemic.

Chloe Rodriguez speaking about her photography project at the Bronx Documentary Center.

The photographer and her work.

The South Bronx, a neighborhood that stretches about four square miles, ranked higher in its rate of fatal overdoses than nearly all 50 states in the U.S. in 2017. The only state that ranked higher was West Virginia, DOH said last year. In 2018, drug overdose deaths decreased in New York City overall for the first time in eight years, but in the Bronx, deaths still rose. There were 391 overdose deaths in the Bronx, significantly more than any other borough. The Hunts Point and Mott Haven neighborhoods in the Bronx had more than twice the overdose rate of the rest of the city.

There are eight methadone clinics in Mott Haven, more than any other neighborhood in New York City. The Hub earned its name from the seven bus and train stops in its junction. The foot traffic and concentration of clinics makes the neighborhood a destination for addicts from all boroughs, Rogers said.

“This is the Grand Central Station. This is the Home Depot of heroin,” Rogers said.

Cracks in the sidewalk on East 150th Street

Several community members have said they’ve seen the problem grow more visible after the summer of 2017. The Daily News published a “shooting gallery” painting a gruesome picture of an abandoned railroad track and popular site to shoot up in Mott Haven called “the hole.” The story drew attention to the drug epidemic in the neighborhood, but it also pushed the city off course from its original plans to fix the problem.

The Mott Haven Herald reported in February 2018 that city agencies had been working with harm reduction organizations on a plan to address the decommissioned railroad tunnel at St. Ann’s Avenue and East 150th Street, which involved long-term treatment resources. All of that fell apart when the Daily News story ran. Instead, the mayor’s office ordered that “the hole,” a haven for the homeless and those afflicted with addiction, to be quickly closed, bulldozing over the plastic syringes and even handcuffing some of the tunnel’s residents.

“I don’t think it’s safe to have a place where people can congregate to do something that’s dangerous,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said to The Daily News. “I believe that’s the right strategy, to constantly limit the places where people can engage in illegal and dangerous activity.”

But the illegal activity hasn’t slowed down at all, Rogers and Take Back the Hub argue. It’s spilling out into the sidewalks, stoops and playgrounds.

Take Back the Hub started in October of last year as the problem seemed to crescendo into sexual violence. That month, an 82-year-old woman fought off an attempted rape sitting on the front porch of her home in broad daylight, steps from a daycare center. Many believe the assailant was high, but police still have not arrested a suspect. While drug use is not directly linked to sexual assault, Rogers saw the incident as a sign the neighborhood was no longer safe for anyone.

“It was the last straw,” Rodriguez said.

Soon after Rogers formed the committee, he and Sister Patrice Owens, the principal of Immaculate Conception School on East 151st Street, organized a protest called “Sound the Alarm.”

About 20 to 25 people showed up, including parents and their children, who either attend Owens’ Catholic school or one of the other five schools surrounding the Hub. They made posters and signs. Kids gave speeches. The adults picked up needles around the neighborhood and dropped them into orange juice bottles.

Marty Rogers, along with his wife Francine and friend Anthony Dalton, join together in prayer at the Hub.

Now, every week, Rogers and a handful of others display a few of these bottles in the Hub. Rogers writes with chalk on the concrete, “God Bless the Hub of Heroin.”

Every Tuesday, Marty Rogers and other members of Immaculate Conception Church head to the Hub and ask passersby to write down what they wish for their community in chalk. Here, he adds a heart to his message.

Rogers, who usually tucks his long gray hair into a low ponytail, grew up in the Hub. He went to Immaculate Conception School as a child and his mother attended the school before him.

Marty Rogers points down to show needles in the area outside his church, Immaculate Conception on East 150th Street.

Rogers is retired. He plays guitar in the mass choir. He and his wife have planted a community garden on East 151st Street. Owens said that if you live in the neighborhood, you know Marty. “He’s the mayor,” she said.

“I think the kids look up to Marty and the other older folks as examples of how to be an activist and how to speak truth to power,” Owens added.

Marty Rogers introduces himself to those in the community who inquire about his mission and messaging with chalk.

Rogers and Owens encourage the seventh and eighth graders of Immaculate Conception to join the committee. And several recent graduates of the Catholic school, including Rodriguez, have become members.

When he talks about the teens involved in the Hub, Rogers’ eyes grow a little misty. He tells of Chris, who is the best public speaker anyone’s ever heard; and Chloe, who takes beautiful photos that tell stories of her neighborhood in conflict.

But there’s a hint of sadness too. Rogers said he remembers summer nights as a teen, when he played softball in the middle of East 151st Street with the area kids. He’s afraid those days are gone now.

There has been some progress since the group started, Rogers and the teens say.

In November, de Blasio said the city would spend $8 million on programs to fight addiction and overdose in the Bronx. And Police Commissioner James O’Neill held a private meeting in the neighborhood last spring to discuss how police can have a stronger presence. The Department of Health also announced it would be investing in a 24-hour drop-in center in the Hub, which will likely include a needle exchange and overnight health services.

Figuring out how to properly police the opioid crisis has been a challenge for the 40th precinct. In January, Bronx narcotics officers busted a group of 10 alleged drug dealers, the biggest sting operation in a decade.

Former Deputy Inspector Brian Hennessey said police officers in the neighborhood try to target large-scale dealers and avoid excessive force when it comes to users and small-time corner dealers.

“We’re not here to antagonize anyone,” he said. “We’re here so a 7-year-old can safely cross the street without being harassed by drug dealers. This is about the children of this community.”

Councilmember Diana Ayala — who represents the district and is also the chair of the council’s Committee on Mental Health, Disabilities, and Addiction — said she has been working with multiple agencies to clean up the debris of drug use in the neighborhood, including working with the Department of Sanitation to expand the Environmental Police Unit.

“Our neighborhood is in the midst of a severe epidemic that is inextricably tied to years of disinvestment, but with constant collaboration and consistent resources, we can end this crisis,” Ayala said.

But for young residents like Rodriguez, it feels like law enforcement is waving a white flag to the dealers and the users in the community. It feels, she said, like her neighborhood is no longer for her.

Needles and garbage strewn across the bushes outside Immaculate Conception Church.

She lives right next to St. Mary’s Park, a huge, hilly stretch of green. In the summer, she used to smell the smoke coming off grills, as folks barbecued meat and ate corn on the cob.

Now, when Rodriguez tries to cut through the park on her evening commute home, she said, she gets stopped by police officers. They tell her not to go inside.

“That's where people go and shoot up,” she said.

So she takes a longer route.

Lydia Monserrate is one of those people Rodriguez avoids. She says she has been addicted to heroin and cocaine for about five years, and is homeless. She has welts and bruises all over her small body. But as she tosses out a McDonald’s bag down on a hot July afternoon, her voice escapes her petite frame with a loud, raspy power to it.

Lydia Monserrate, 30, struggles with addiction to coke and heroin. She grew up bouncing around foster care homes across New York City and is currently homeless. She wants to get help.

“These cookies are going to be HOT later,” she says.

She has a mop of black curly hair. One chunk looks like it was bleached long ago. And her black and white striped dress is just a little bit too long — touching the concrete periodically as she strolls through the streets. She wraps it up at one point around a strap so she can walk with ease.

She pulls her hair back behind her ear, revealing an earlobe severed in half— she says in high school, girls would jump her and rip her earrings out. Monserrate, 30, grew up in foster care, bouncing around 15 different childhood homes across the city. She almost cries, but stops herself. Her mother broke her heart by leaving her, she says.

Lydia Monserrate’s struggles with addiction have left her bruised and scarred.

Her Facebook profile, Princess Mercedes Valentine, is a time capsule of who she used to be. The background photo is a collage of her young son. She says sometimes she looks at her profile pictures from 2015 and 2014 and hardly recognizes herself.

“They say drugs change you,” she said. “They really do.”

Lydia Monserrate has a sad gaze — she’s been through a lot in her life, with some scars going unseen.

The previous evening, she slept on a park bench at St. Mary’s. She steals to get by.

“If people wanna know how I survive out here — I’m a booster,” she says, with a smirk and a hint of pride. “You know what that is? A shoplifter. That’s why I can’t go into CVS.”

Outside McDonalds, another woman is asking strangers for money. Without pausing to think, Monserrate pulls an apple out of her pocket and hands it over.

Dear Rachel and Niamh, Thank you for your work. It is very powerful and has me stunned here tonight. You capture the pain and hope and the efforts and the feeling of helplessness sometimes. We are in God’s hands. We are still at it , we meet on Thursdays now. Thank you , Sisters. If it fits your schedule please come up again for a walk and let’s go get dinner with our crew. God bless you. I hope your studies are going well and I guess will be nearing completion. peace, Marty.