![]() Almost all youth who interact with the juvenile justice system have contact with juvenile probation staff. Juvenile probation officers (POs) often conduct intake interviews with youth and make recommendations to judges about diversion, case processing and out-of-home placement. Typically, POs play a big role in the lives of youth placed on probation following adjudication. They meet with youth regularly, reconnect them to school if necessary, and ensure youth meet the conditions of their probation agreement.

Almost all youth who interact with the juvenile justice system have contact with juvenile probation staff. Juvenile probation officers (POs) often conduct intake interviews with youth and make recommendations to judges about diversion, case processing and out-of-home placement. Typically, POs play a big role in the lives of youth placed on probation following adjudication. They meet with youth regularly, reconnect them to school if necessary, and ensure youth meet the conditions of their probation agreement.

Johanna Lacoe

However, many jurisdictions are reconceptualizing and reforming these traditional ways juvenile justice systems interact with young people. Because juvenile probation plays a central role in the juvenile justice system, reform efforts require buy-in from leadership and staff of juvenile probation agencies.

Leah Sakala

Building on the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), which aims to reduce the number of youth in detention across the country, the Foundation’s Deep-end Initiative seeks to reduce out-of-home placements, particularly for youth of color, by catalyzing reforms within juvenile justice systems. In our evaluation of the deep-end initiative between 2014 and 2019, the Urban Institute and Mathematica focused on the central role of juvenile probation leadership and staff in these efforts.

Understanding what POs say they do, value is important

Juvenile probation practice is undergoing a fieldwide shift away from a punishment and compliance orientation, toward a rehabilitation and youth development orientation. But we know very little about the experiences of POs in the field, which makes it harder to develop collaborative reform strategies. What are POs’ values around accountability? What do they view as the goals of their work? What is their knowledge of adolescent development? What are the day-to-day practices that they put in place?

Through our evaluation work with the Casey Foundation, we conducted a survey of probation staff, called the Juvenile Probation Policies and Practices Survey. The survey was administered to probation staff in 11 jurisdictions that participated only in JDAI and 12 jurisdictions that participated in JDAI and the Casey Foundation’s Deep-end Initiative.

The survey included questions about typical probation practices, such as providing supervision and documenting progress on probation conditions, as well as reform-oriented practices, such as strategies to engage youth, families and communities and efforts to address racial and ethnic equity and inclusion in probation practice.

Survey respondents were either POs (68%) or their supervisors (32%). The majority of the respondents were female (56%). About one-third of respondents were in each of three age categories: under 40, between the ages of 40-49, and 50 or older. Forty percent of respondents were white, 35% were black and 17% were Hispanic. The average tenure in the agency was 14.5 years.

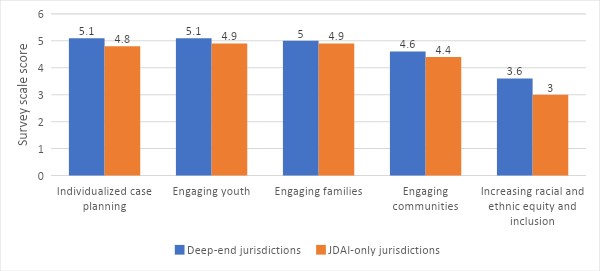

In response to questions about probation practices, we found that probation staff in both Deep-end and JDAI-only jurisdictions most frequently reported using individualized case planning practices (such as developing a plan that is based on youths’ unique needs) and practices to engage youth and families (Figure 1). Engagement practices include actively working to motivate youth to change behaviors and engaging family members in developing the case plan.

Probation officers reported less frequent use of practices explicitly aimed to engage communities (such as developing personal relationships with community groups or faith-based organizations), along with practices intended to increase racial and ethnic equity and inclusion (such as talking with other POs about possible racial and ethnic disparities in violations of probation or other decision points).

Figure 1. Average reported probation principles and practices

Source: Juvenile probation policies and practice survey, Wave 2 administered between March 2018 and July 2018. Statistics reported in Esthappan et al. 2020. The survey asked how often respondents used each of 22 principles and practices items in their work with youth on probation and had the same six-option response scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Higher scores indicate more frequent use of principle or practice.

Collaboration can advance probation reform

The survey results suggest that even in jurisdictions participating in deep-end reforms, there is room for improvement in practices that align with the reform effort. Ensuring that POs are familiar with probation best practices and engaged in reform, therefore, is critical to improving juvenile probation. Engaging POs can help achieve broader changes in juvenile justice system orientations and outcomes, and in particular, reducing racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes. The roles POs play in probation reform depend on the specific needs and context of each community. POs can participate in a variety of ways, which alone or in combination may advance reform efforts.

Jurisdictions that are beginning to take on juvenile justice reform may find that PO participation in training can be valuable. Ensuring that probation officers are familiar with best practices regarding positive youth development, case planning with families and working with community partners can help pave the way for reform. These trainings can be conducted by agency staff or by an external organization such as Justice for Families, which offers assistance with forging stronger partnerships with the families and caregivers of justice-involved youth.

POs can serve as integral partners to guide program development and innovation. POs are on the front lines interacting with youth and their families on a daily basis and are in strong positions to weigh in on strategies to better support their clients. One example of a jurisdiction that focuses intensively on strengthening probation program design is Pierce County, Wash., which developed its Opportunity Based Probation with an initial pilot designed in collaboration with four POs, a local researcher, and youth and their families. The approach in Pierce County relies on an incentive-based supervision system that incorporates family engagement and involves both long- and short-term goal setting. The jurisdiction expanded the program after local leaders and staff observed positive outcomes among participating youth.

A third role that POs can play is helping implement reforms such as new processes or case planning or screening tools. Both probation supervisors and line staff can lead change efforts within their departments by making the tools more relevant to their specific context, helping to secure buy-in from peers and ensuring that reforms are carried out with fidelity. POs are also positioned to share implementation feedback and suggest process improvements to agency leadership.

Finally, POs can serve as valuable internal and external resources for those seeking to understand and implement reforms. Peer education is an important element of deep-end reform, and POs can learn from both their colleagues and their counterparts in other jurisdictions as they all work to better serve youth. Leading trainings, serving as resources to colleagues and teaching stakeholders in other jurisdictions about innovations are all ways that POs can help each other understand and champion improvement efforts. Additionally, some stakeholders report that POs who are less familiar or comfortable with reforms may be more open to learning about them from a messenger who is a peer.

Improving juvenile justice outcomes can require adjusting both policy structures and agency culture and practice, often at the same time. Ensuring that probation supervisors and officers are involved from the outset can strengthen improvement efforts on both fronts.

The experiences of the deep-end jurisdictions have shown that no single stakeholder has all the answers, and probation reform can require time, patience and willingness to work through disagreement. But as initial research findings show, broad collaboration across stakeholders can help advance efforts to improve probation and achieve better outcomes for youth.

Johanna Lacoe, Ph.D., is research director of the California Policy Lab at the University of California, Berkeley, and a policy scholar with expertise in criminal and juvenile justice, education, employment and housing.

Leah Sakala is a senior policy associate at the Urban Institute Justice Policy Center, where she co-leads a team focused on criminal and juvenile justice reform and supporting community-driven safety solutions.

Way back, in the late 1960’s – early 70’s, I was a Juvenile Probation worker. Have caseloads improved enough to make individualized, needs based planning AND supervision are actually possible? And how wide spread is this.

Most of the juvenile probation reforms we studied – particularly those programs that target youth assessed to be high risk/high need – required smaller caseloads due to the more intensive and personalized nature of the work. However with youth crime falling and more low-risk youth in these jurisdictions being diverted from probation altogether, many departments have been able to reduce caseloads.