![]() Though it’s been 12 years since I visited, an image from a juvenile confinement facility in Alabama remains vivid in my mind’s eye: a simple wall, visible from a glass control room, separating two identical wings of small concrete cells.

Though it’s been 12 years since I visited, an image from a juvenile confinement facility in Alabama remains vivid in my mind’s eye: a simple wall, visible from a glass control room, separating two identical wings of small concrete cells.

This wall had been built during the Jim Crow era to keep young people separated by race. It shook me to realize that the wall had become obsolete, not because of the civil rights victories of the 1960s. Rather, it was because virtually all the boys housed in the facility that day, on both sides of the wall, were kids of color.

Danielle Lipow

The lesson of that day still rings true — not just in Alabama, but throughout the country. Most jurisdictions effectively operate two juvenile justice systems: one for white and Asian kids, and the other for African American, Hispanic, Native American and other kids of color.

Although the overall number of young people confined by the justice system has been shrinking for decades, pervasive disparities remain. Among the 62,000 young people nationwide placed in juvenile facilities in 2018, kids of color were drastically overrepresented. For instance, African American youth were more than four times as likely to be confined as their white peers.

Deeply rooted in our nation’s long and shameful history with race, these disparities represent a monumental injustice, a betrayal of our stated national ideals. In most parts of the country, this imbalance has been growing worse in recent years, not better.

That is why I am so pleased to report that, finally, some hopeful news is emerging to show that racial disparities in juvenile justice are not immovable. At precisely the moment when the COVID-19 pandemic has made emptying juvenile facilities a moral and health imperative, a new report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation provides early evidence that public systems can safely and significantly reduce the number of young people we lock up, especially African American, Native American and Latino males.

12 sites show promise

The report, “Leading with Race to Reimagine Youth Justice: JDAI’s Deep-End Initiative,” describes the progress made by 12 jurisdictions across the country that have dedicated themselves to reducing their reliance on confining young people. The focus of the Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative® is the initial detention phase just after arrest. However, these jurisdictions also put emphasis on the subsequent phases known as the “deep end” of the system, when youth may be placed into institutions after being found delinquent in court. In their work, the 12 jurisdictions are focusing intently on racial and ethnic equity in order to dismantle the structural racism built into their local justice systems. It seems to be working.

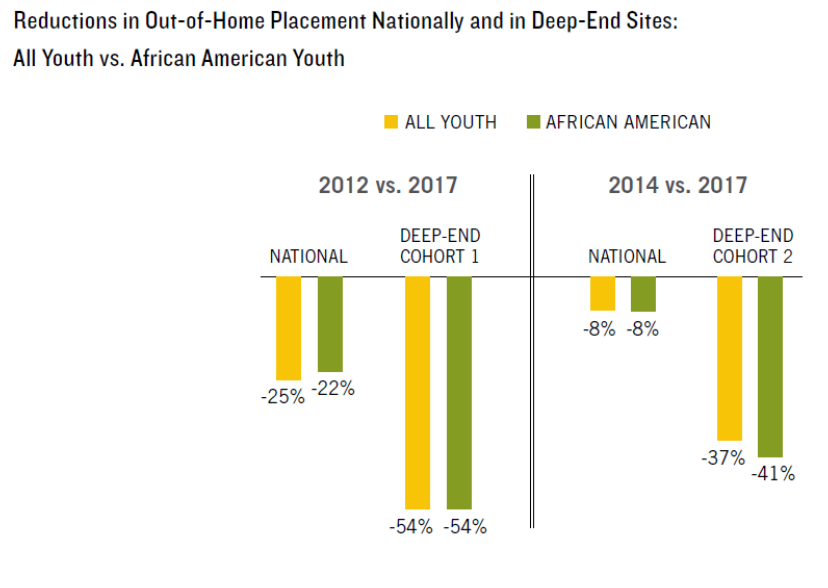

Early results show that participating sites are significantly outpacing the national average in reducing confinement generally. They are also lowering confinement rates at least as rapidly for African American youth as for white youth.

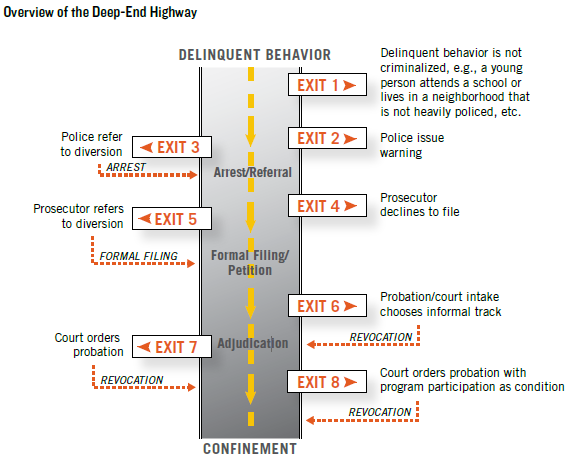

The jurisdictions are following three core strategies. The first is race-conscious system mapping, which involves creating a map of their “Deep-End Highway.” This is a metaphorical roadway that begins with delinquent behavior and ends in confinement. As on an actual highway, each jurisdiction has many exits that can steer the young person away from confinement, such as alternatives to arrest, diversion from juvenile court, probation practices that emphasize positive behavior change rather than rule compliance and opportunities to participate in youth development programs that promote personal growth and connection.

These exits are often attached to reentry points, or on-ramps, that can steer a young person away from community connections and continue their journey toward confinement. These on-ramps include determinations that an attempted diversion has “failed” or that a youth has violated probation due to rule-breaking or failure to comply with probation rules.

Research shows that at each exit, youth of color are consistently less likely than white youth to leave the highway. Among those who do exit, youth of color are more likely than white youth to be ensnared in an on-ramp that drives them back toward confinement. By mapping exits and on-ramps, participating sites begin identifying decision points where there are opportunities to reduce confinement, particularly for youth of color.

The second strategy is aggressively tracking data, disaggregated by race and ethnicity, from which jurisdictions can analyze their systems and measure progress. Here, it is essential to examine all forms of out-of-home placement, not just state correctional institutions. Even if a facility is labeled as a group home or residential treatment, the placement still forcibly removes the young person from his or her family, disrupts the educational process, precludes participation in normal rites of passage associated with adolescence and throws young people into an artificial environment.

The data analysis process allows system leaders to examine all the factors associated with confinement. For instance:

- How often are police using alternatives to arrest for young people involved in lower-level delinquent conduct, and how does this vary by race and ethnicity?

- Following arrest and referral to court, what share of white youth compared to black and Hispanic youth are diverted to community programs rather than being sent to court?

- How many placements into residential facilities are due to violations of probation rules, rather than delinquent conduct?

- How many young people are offered the opportunity to participate in constructive, community-run youth development programs?

- How do participation rates and success in such programs vary by race and ethnicity?

By compiling and analyzing data on these and other questions, local leaders begin to identify the key drivers of unnecessary placements in their jurisdictions. They can uncover the factors that perpetuate racial and ethnic inequalities in their systems.

The third and final strategy is developing targeted reforms. Jurisdictions develop and test new strategies to reduce the use of confinement, especially for youth of color. By regularly examining their data, communities can continually assess the effects of their work and modify their strategies. Specifically, there are opportunities in five areas:

- sentencing that limits the reasons for which youth may be confined;

- diversion to reduce the use of arrest and formal justice system processing in response to delinquent conduct (and instead, address behavior in the school, family or community);

- probation practice to develop individualized case plans; having probation officers assume a coaching role, rather than one of surveillance and compliance; shift from sanction-based approaches to incentive-based ones;

- family engagement to support family members who remain the most important people in their children’s lives, and to encourage their full participation in their children’s cases; and

- community engagement to strengthen connections between the justice system and the community, and to develop or expand community-based alternatives to placement that are designed and led by people who live in the neighborhoods most affected by the system.

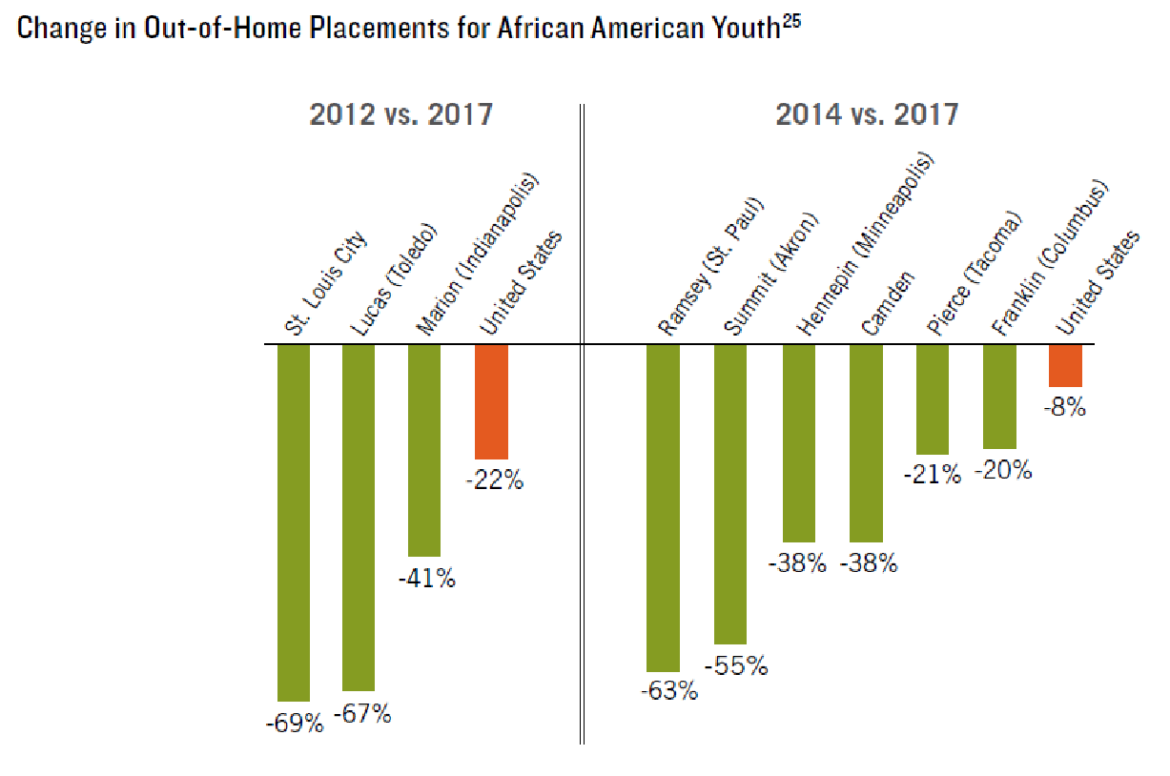

These strategies have shown encouraging early results. All nine of the jurisdictions for which we have baseline data have reduced overall confinement by more than the national average since beginning the deep-end work, and all nine have reduced confinement among African American youth by far more than the national average (see the figure below; these are counties, with the exception of the city of St. Louis.).

Meanwhile, the deep-end sites report that juvenile crime rates trended downward during this period in which they sharply reduced confinement.

Thinking back to my visit to the Alabama facility, the first and most important lesson I take away from our work in the deep end is that to make a significant dent in racial and ethnic disparities, we need to employ strategies that focus explicitly on race. Our systems cannot sit back and expect that so-called race-neutral reforms will erase the troubling inequity that has become the signature characteristic — the shame — of our nation’s juvenile justice systems.

If we want to tear down that wall, we must dedicate ourselves to recognizing and offsetting the structural, institutional and long-established factors that have perpetuated a system of unequal justice.

Danielle Lipow is a senior associate at the Annie E. Casey Foundation.