Orange County in North Carolina has two school districts. One is much tougher than the other on students caught with marijuana on campus.

The upscale Chapel Hill/Carrboro City district allows students four pot offenses before they’re referred to teen court or the juvenile justice system. The other, Orange County schools, which spends about $2,000 less per student than its neighboring district, allows only two such offenses before a teen has contact with the system. That’s according to Kate Giduz of Volunteers for Youth, the coordinator of the teen court in Orange County.

Volunteers for Youth

Kate Giduz

In Chapel Hill/Carrboro City Schools 28% of students are black or Hispanic, while in Orange County Schools, where the pipeline from school to courtroom is much shorter for marijuana offenses, 38% of students are black or Hispanic.

Compared with their share of the population, black youth in North Carolina are vastly overrepresented in the justice system. But the state’s recently implemented effort to expand juvenile jurisdiction to include all those under 18 was a race-neutral undertaking — it was not designed to kill two birds with one stone. Still, youth advocates see the implementation of raise the age as a time to address disproportionality while youth justice is still fresh in the minds of policymakers.

Office of Juvenile Defender

Eric Zogry

“We have the hope that with raise the age, Juvenile Justice can do a better job of impacting the disproportionality that has been there forever,” said Eric Zogry, the state’s juvenile defender.

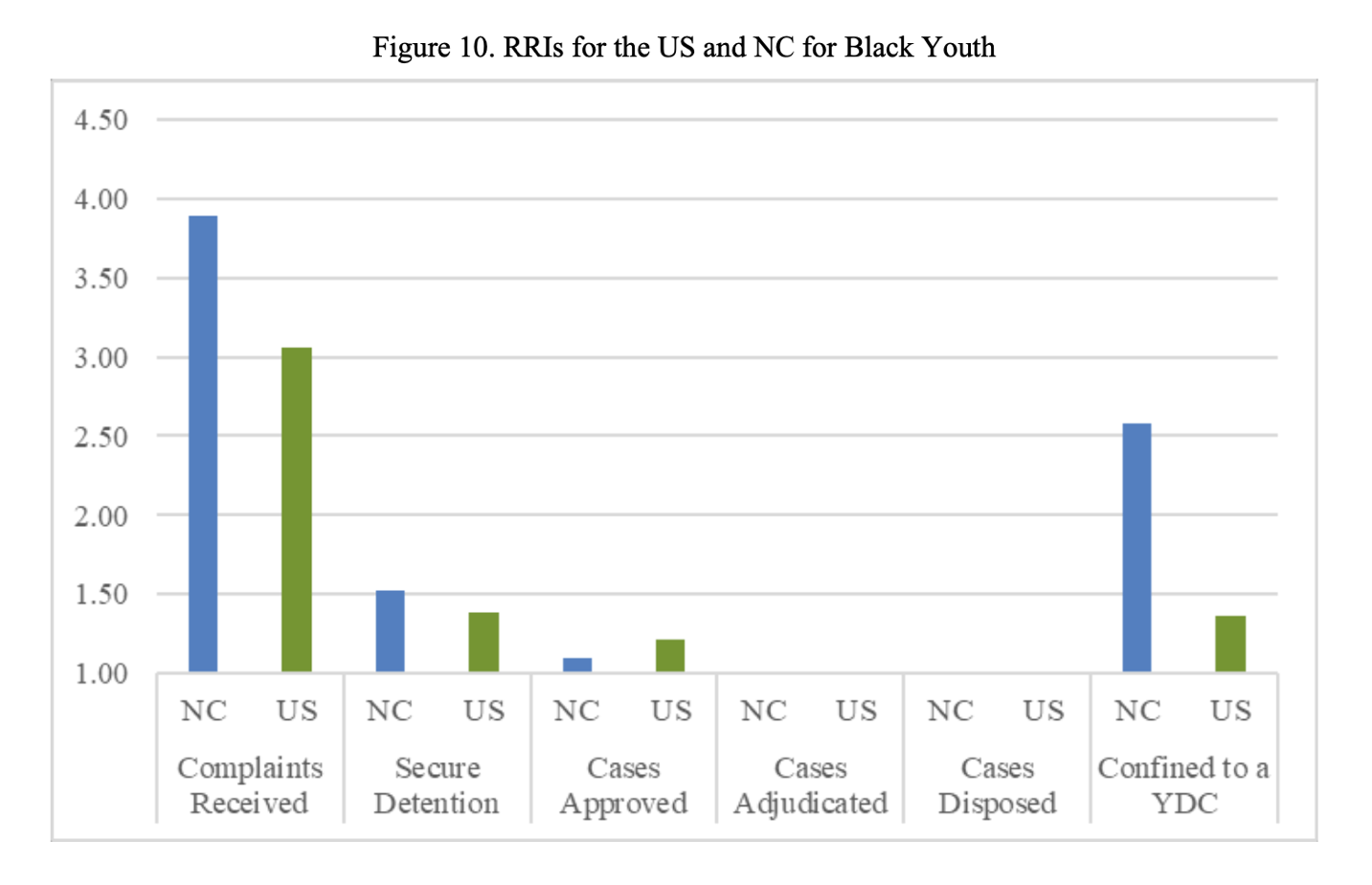

This phenomenon of “disproportionate minority contact” (DMC) persists nationwide. It is, however, by some measures worse in North Carolina. A study commissioned by the governor’s Crime Commission and other state entities found last year that the overrepresentation of black youth was greater in North Carolina, especially in terms of complaints received and confinements in youth development centers — the outset and the outcome of many youths’ contact with the juvenile system.

(From North Carolina’s 2019 DMC study. RRI stands for “relative rate index,” where 1.0 is proportionate representation of black youth at any given point in the juvenile system, and anything above 1.0 denotes overrepresentation.)

.

While roughly a quarter of North Carolina’s youth population is black, black children account for three-quarters of its confined youth. Nationwide, 42% of boys and 35% of girls in juvenile facilities are black, though only 14% of all youth under 18 in the U.S. are black, according to a 2019 study by the Prison Policy Initiative.

And in the state’s two biggest counties, Mecklenburg, which includes the largest city, Charlotte, and Wake, which has the state capital, Raleigh, not a single white youth was confined to a youth development center in fiscal 2018.

Teen courts, SJPs expanding

North Carolina has in recent years seen a sustained drop in youth complaints and detentions, tracking nationwide trends. It’s also acknowledged the problem of overrepresentation of minority youth in the system, collecting data that’s separated by race and promoting initiatives that keep students out of the juvenile justice system. Those include teen courts and school justice partnerships (SJPs).

“School-to-prison pipeline used to be a theory. Now I think it's commonly accepted as a phenomenon that needs to be addressed, which is evidenced by North Carolina’s implementation of school justice partnerships. That was part of raise the age,” Zogry said.

North Carolina’s raise the age law of 2017 authorized the Administrative Office of the Courts to establish guidelines for all 100 counties statewide to set up SJPs, with the aim of applying age-appropriate progressive discipline while reducing in-school arrests as well as suspensions and expulsions. As of Jan. 18 counties had an established SJP, including the most populous, Mecklenburg.

North Carolina’s raise the age law of 2017 authorized the Administrative Office of the Courts to establish guidelines for all 100 counties statewide to set up SJPs, with the aim of applying age-appropriate progressive discipline while reducing in-school arrests as well as suspensions and expulsions. As of Jan. 18 counties had an established SJP, including the most populous, Mecklenburg.

Other legislative action targeted an expansion in the use of teen courts. In 2019, the state’s General Assembly changed the law so youth could be referred to the teen court system more than once, and thereby continue to avoid a permanent criminal record.

Giduz of the Orange County Teen Court said in recent years school resource officers have become much more likely to refer cases directly to teen court, rather than first file a complaint with the juvenile system. Five years ago, she said, about 70% of the cases she saw were referred first to Juvenile Justice, but now about 90% go directly from officer to teen court.

“I think teen court is a fantastic program, but I do think one thing to be careful about is still we don’t want to overuse that, either,” she said. “On paper it reduces DMC in the juvenile system, but it’s just increasing it in the teen court system.”

Some advocates believe school-justice partnerships won’t reduce DMC, either.

Tyler Whittenberg

“SJPs, I think, is a very friendly way of saying, ‘By what means are we going to introduce youth to the juvenile system?’” said Tyler Whittenberg, chief counsel, justice systems reform for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice.

For Whittenberg, the goal is bigger even than ending DMC – it’s to “eliminate this concept of youth criminalization.” And to achieve that, a prime focus is eliminating police presence from schools, where 44% of juvenile complaints originate in North Carolina as of 2018.

He said memos of understanding (MOU) between school boards and local law enforcement departments often give too much discretion to school resource officers to arrest students for offenses that could be handled instead via school discipline. His group is currently working with the community in Wake County to update its school district’s MOU, which expires July 1 and drew criticism when it was enacted in 2017 from the American Civil Liberties Union for its lax requirements for documenting officers’ use of force.

“Everyone agrees that a law enforcement official should not act as a disciplinarian,” Whittenberg said. “Their job isn’t to provide mental health or other supports for students. Their job is to enforce the law. That is the problem. They’re incongruent institutions.”

Advocates agree the problem of disproportionate minority contact in North Carolina and nationwide is deeply embedded, with no ready solutions.

“If somebody had figured it out by now, wouldn't we all be replicating it? I don't want to say it's intractable. I don't think that's true,” said Zogry. “You got to make some hard decisions about policy.”