Video by Roger Newton

ATLANTA — Torch has been on the street 11 years, he says. With no fixed address, he is a permanent resident of Little Five Points, a robust business district of mom and pop entrepreneurs in east Atlanta.

Born Kyle Latrell, he was a homeless 17-year-old from Illinois. Now he is a homeless 28-year-old.

He takes amphetamines, eight a day, he says. He has been arrested for marijuana possession and it is not certain what other drugs he takes, or how often. His constant twitching could be the drugs or it could be Tourette Syndrome, a neurodevelopment disorder that strikes in childhood. Latrell says he was diagnosed with Tourette’s when he was younger.

He has been arrested 11 times since 2010, once for aggravated assault, according to Fulton County jail records.

Latrell is smack in the middle of an intersection where many homeless people crash. Experts say many people experiencing homelessness have experienced trauma as young people or have mental illness issues. Then they self-medicate. The use of drugs leads to addiction, loss of job and homelessness. Finally, there is a berth in the criminal justice system because when they’re scratching to survive on the street, they commit crimes.

In the South, people with perceived mental illness used to be warehoused in places like Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, Ga., once the world’s largest mental institution, or Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, Ala., which was called Alabama State Hospital for the Insane. If this were the 1950s, Latrell and his fitful ramblings would have a place all his own in Central State or Bryce, which were built before the Civil War.

In time, society and the courts decided community care was much better than institutional confinement. Central State was emptied out and now decays. The Bryce property was sold to the University of Alabama.

But there is still a huge need in the South. According to a 2018 study by the United Health Foundation, Alabama had 93 mental health care providers per 100,000 people compared to 591 per 100,000 in Massachusetts. A report by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on mental health remedies in Georgia found that the state discharged mentally ill patients to extended-stay motels and homeless shelters rather than continued care.

No social worker on beat

It is easy to see why Latrell has languished on the streets for so long: mild weather and inadequate societal response.

Tom Gissler, the Atlanta Police Department’s community police officer for Little Five Points, has been on his beat for only several months, but he has gotten personal enough with “Torch” that it was Kyle Latrell, not Torch, who showed up the day after Gissler arrested him and thanked the officer. “He said he needed a break from it all,” Gissler said.

But, of course, Latrell returned to the Little Five Points cauldron. Until mid-May, he slept behind a bar and the amount of debris piled up suggested he had been there a while. The alley has since been cleaned up because a new tenant moved in, and Latrell is on the move.

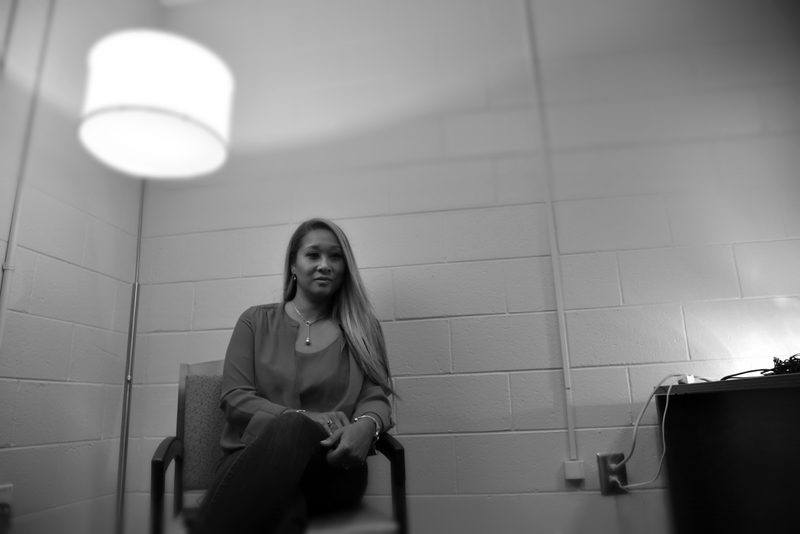

Roger Newton

Debbie Stevens, a psychiatric nurse practitioner with Mercy Care in Atlanta, says her patients can be traumatized if their treatment occurs in a converted old jail.

Is there a better answer than triage of well-meaning community programs?

Gissler was chatting with Georgia state Rep. Bee Nguyen, a Democrat, in the Little Five Points precinct office one morning and pointed to a desk and empty chair. He said there is space in the office — and on the beat — for a social worker, or some other clinician who could dissect some of the local mental illness issues. Gissler said he doesn’t mind practicing social work, but he is a cop and his only tool is a set of handcuffs.

“I'll tell anyone who will listen we do not have a homelessness problem, we have a mental illness and methamphetamine problem,” Gissler said. “Homelessness is not the issue, it's a symptom.”

The next day, Nguyen was making calls to see if she could get some traction toward a social worker for Little Five Points.

But, “The fact they are experiencing chronic, severe mental health issues could impact their insight and their ability to connect that they can get resources if they are in some kind of acute or psychiatric crisis,” said Debbie Stevens, a psychiatric nurse practitioner with Mercy Care in Atlanta. “They don’t have the insight to see they need help.”

One-third of the homeless population in the nation are people with untreated mental illness, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit dedicated to the issue of severe mental illness. And lifetime arrest rates ranged between 62.9% and 90%, according to a 2014 review of 15 studies on the correlation of mental illness, homelessness and criminal justice by The American Psychiatric Association.

‘Here by choice’

For young people who were runaways or homeless, a staggering 78% had some interaction with the criminal justice system.

Melody McLaurin

Kyle “Torch” Latrell has been on the streets for about 11 years. Now he is in an Atlanta neighborhood called Little Five Points.

Mental health, homelessness and criminal justice are so entwined, Stevens said, that simply walking into a shelter could trigger stress in a homeless person who has churned through the criminal justice system from a young age.

“I have clients who have intersected with the criminal justice system and have been incarcerated, and sometimes shelters have a lot of restrictions and structure that reminds them of being in jail,” she said. “I am working in a shelter-based clinic, and the shelter is an old jail. It can trigger them and traumatize them. In fact, my client this morning said, ‘I don’t know how much longer I can last in the program because it’s like the old county jail.’”

Scott Pendergrast, the president of the Little Five Points Business Association, a property manager and co-owner, tires of so many alibis for the homeless who refuse help. He insists Kyle Latrell is not a harmless lost soul.

“He went to prison for aggravated assault of a waitress getting off work at 2 a.m. in Little Five Points,” Pendergrast said. “He tried to strangle her. And now he’s back here.”

He is trying to protect business owners and customers from what he sees as society’s reluctance, or inability, to handle the homeless and addiction crisis, particularly in Little Five Points. He had to spend several days in the Fulton County courthouse to have protection orders served against two drug-addled men who repeatedly committed assault and battery and property damage, he said.

“The [homeless] folks that are here in Little Five Points are here by choice because they are having their needs met and they would be denied their drugs of choice if they accepted assistance and housing,” Pendergrast said. “Everyone can be helped and it would require intervention and telling these folks ‘No, you don’t have the right to shoot up and defecate behind someone’s property and scare the customers.’

Roger Newton

Georgia state Rep. Bee Nguyen understands from her college boyfriend’s story how family turmoil can leave emotional scars and lead to a life on the street.

“This situation is not good for anybody.”

At the same time, Pendergrast once helped a teenager, homeless in Little Five Points. He found the family and bought the teen a bus ticket home to overjoyed parents in Savannah.

Karen Taber, a resident of the nearby Inman Park neighborhood, joined the campaign to bring Little Five Points homelessness under control. She became the chairperson of a neighborhood initiative on homelessness.

When a group of homeless people were rousted from living behind an abandoned house in the neighborhood, she said, she found things that had been stolen from her shed. There were also frames from stolen bicycles, whose parts had been sold at a sort of chop shop for bikes on nearby Moreland Avenue.

Taber became familiar with the homeless and saw the deprivation up close.

“From my experience it’s the perfect storm,” she said. “Kids that maybe have anxiety that’s not treated going into adolescence and puberty, and they start self-medicating, perhaps with cigarettes and then something else stronger, like meth.

“I got burned out. I didn’t have the skill set to deal with them. And then the feedback was they are not seeking help. There are programs in Atlanta for people who are homeless because of economic issues, but the ones with mental health issues, they are on their own.”

Family turmoil can lead to street

Rep. Nguyen, the founder of Athena’s Warehouse, a nonprofit empowering young women in east Atlanta, is intimate with the multipolar issue of mental illness, substance use, homelessness and crime. She was in college at Georgia State University when her boyfriend became homeless, addicted to cocaine and dependent on alcohol. He committed suicide.

Nguyen, who took Stacey Abrams’ seat in 2017 when Abrams started her run for governor, worked arduously to drag “Walt” back to normalcy. She couldn’t. He grew up with some turmoil in his family, she said, and it set him on a path.

“He had a very unstable household and there was some physical abuse involved, that’s how it started,” she said. “He suffered from depression. He had a history of addiction.”

Nguyen has spent time at Cross Keys High School in DeKalb County, Ga., where 77% of the students receive free or reduced lunch, according to Georgia Department of Education data. Poverty creates stress for parents and children. Nguyen understands through Walt’s story how family turmoil can leave emotional scars and lead to a life on the street.

“There is a lot of trauma in the household, and these kids need mental health support,” she said. “You are talking about abuse, and domestic violence. The intersections are so great, right? I mean, part of it is access to education. Because when you give kids a tool and a purpose and a meaning, they're less likely to drop out of school and be on the street.”

It’s why she fought so hard against Senate Bill 15 in the 2019 legislative session. A provision of the bill required a school administrator to call police if there was reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

“There was no distinction about what criminal activity would look like, and it would be up to the discretion of the school coordinator,” Nguyen said. “And because there was no distinction, it really opens the door for targeting kids or misreading behavioral issues.”

The connection to homelessness is that if a student is suspended from school it adds to the turmoil at home. Perhaps the student turns to drugs as a way to cope, and ends up kicked out. They land on the street, and slowly, slowly become invisible.

Melody McLaurin

Kyle Latrell focuses on his next barefoot step and next meal at a time.

The othering of the homeless, Nguyen said, is making it difficult to find a remedy.

“As a society, we've become pretty inoculated by homelessness,” she said. “I mean, even as a person who has a more intimate understanding of it, I just think we don't really have any emotional reaction to it anymore.”

State Rep. David Dreyer, a Democrat whose district includes Little Five Points, said he has fought Republicans’ opposition to Medicaid expansion in the state. The additional money would relieve much of the burden on a public hospital like Grady Memorial Hospital to free up funds for mental health treatment of the homeless.

Dreyer also supports wider use of “maintenance medicine” to help opioid users break their habit. In addition, he thinks money should be there for housing for homeless to make sure they stay on a regimen.

All three measures would impact the criminal justice system and the constant churn of homeless through the system.

‘I’m a hammer’

Latrell’s is a bottom-line existence. Asked what’s next for him, he said simply, “Find some food.”

He walks the sidewalks of Little Five Points with his head down, which explains how he manages to avoid broken glass in his bare feet. He said he hasn’t worn shoes in a month and his filthy feet tell the truth of that.

Once in a while he will find treasure lying right there on the sidewalk. His reaction is that of a lottery winner. “Ahhhhhh,” he says loudly and picks up what looks like a leaf. It is a penny-sized piece of tobacco. He pulls the remnants of a vape pipe out of his pocket. He had been fiddling with it off and on for an hour. Now he puts the tobacco in its nest and pulls out his calling card, a red lighter, his torch. He lights up and is in bliss for a few moments.

One morning he was walking along Moreland Avenue and was asked, “What kind of drugs have you taken today?”

“Nothing … got any?” His speech was slurred and he muttered to himself.

“I saw him dancing with a shirt around his waist in the middle of the street,” said Laura Nolan, the owner of Java Lords, a local coffee shop. “I mean, that’s all he had on was the shirt around his waist.

“I have never seen that guy sober. I’m surprised he’s made it this far.”

Officer Gissler said Latrell has gotten high on the fumes of gasoline.

“We have to address this beyond a level of what law enforcement is equipped to handle,” he said. “I try and recognize them as people, see them. But I’m the wrong tool for this job. Atlanta does a better job than other cities in training in use of force, but at the end of the day I’m a hammer. That’s all I have to deal with this.”

He shook his head in dismay. He has a job to do protecting the community; Pendergrast said Gissler is doing a commendable job. But Gissler is exasperated. “These people live between a rock and a hard place,” he said of the homeless.