NEW YORK — K’Juan Lanclos was playing basketball in a park near the Butler Community Center in the Bronx when his friends suddenly fled. Looking up, the then-13-year-old saw a wall of cops running straight at him. Not knowing what else to do, he ran too.

Lanclos said he remembers making it inside one of the nearby public housing buildings and heading for the stairs. He’d just reached the second floor when six angry New York Police Department officers caught him, threw him to the ground and began pummeling him in the ribs. Eventually they handcuffed him, took him to the local precinct and accused him of throwing rocks at police cars.

Scared and angry, Lanclos said he asked to call his mother. “Shut up,” one officer barked. Another slapped the teen in the face. As the hours dragged by, Lanclos knew she would be worried sick. Each request to call her brought more physical violence, he said, and more attempts by the officers to coerce a confession.

“You had fun throwing those rocks, didn’t you!” Lanclos remembers one yelling. “You threw those rocks, didn’t you!” another shouted. Hours later, they read him his Miranda rights. Lanclos was held overnight and released at about 5 a.m., wearing only one shoe. His shirt was torn and his lip was bleeding.

“You had fun throwing those rocks, didn’t you!” Lanclos remembers one yelling. “You threw those rocks, didn’t you!” another shouted. Hours later, they read him his Miranda rights. Lanclos was held overnight and released at about 5 a.m., wearing only one shoe. His shirt was torn and his lip was bleeding.

By the time he got home, he said, his frantic mother barely recognized him.

“It traumatized me,” said Lanclos, now 23. “To the inside of my soul — I felt I was down to the gutter because I didn’t know what to do.”

That’s why Lanclos joined a chorus of voices calling for new legislation that would prevent future generations from having to go through police interrogations alone. A coalition of over 60 juvenile justice organizations and advocates in New York rallied on Thursday to urge state lawmakers to pass legislation requiring police to give children access to an attorney before they can be interrogated.

Sponsored by Assemblywoman Latoya Joyner and Sen. Jamaal T. Bailey, both Democrats, the proposed legislation would limit the ability of police to question a child without an attorney present to only instances where officers “reasonably determine that the child’s life or health, or the life or health of another individual, is in imminent danger.” It must also be determined that “the child may have information that would assist the officer in taking protective action.”

Now when officers detain a child, they are required to make a vaguely defined reasonable effort to notify the child’s parents. Whenever possible, the Miranda warning should be read in the presence of parents. Unless children or their parents specifically ask for an attorney, police are allowed to interrogate the child without one.

If police think the parents won’t show up or if they consider it necessary to interrogate a young person as part of an investigation, they’re allowed to question the child alone, as long as officers determine that the youth is able to understand the Miranda warning.

Kids still treated like adults, advocates say

That gives police too much leeway, juvenile justice advocates say.

Research shows children often do not fully understand the Miranda warning or the long-term consequences of what happens during interrogations, according to Emily Haney-Caron, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice who has researched juvenile false confessions and the impact of justice system policies on youth and their families.

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Emily Haney-Caron

“Youth brains are still developing and that’s especially true for the parts of the brain that are responsible for decision-making and for navigating stressful situations — obviously interrogation is a seriously stressful situation,” she said. “When youth are under stress, they have a harder time processing what's happening, they focus on the short-term consequences, like wanting to get out of there and go home.”

The implications for interrogations of Black children and teens are even more stark, she said.

"Research shows that 94% of 12- to 19-year-olds don't realize the serious consequences of waiving their rights, and research shows that Black youth may be at even greater risk of waiving their rights than white youth because they understandably may not believe that the police are going to respect their rights, even if they do choose to exercise them," Haney-Canon said.

Further, most of those who waive their rights wind up saying something incriminating.

“That's because once youth waive their rights, police officers use the same coercive interrogation techniques with kids as they do with adults and that includes the police suggesting that they have kids’ best interests at heart and also lying about having evidence that the child is guilty — all of that is allowed currently,” Haney-Caron said. The legislation, which stalled in committee last year, is long overdue, she said.

For more information on Juvenile Indigent Defense, go to

► JJIE Resource Hub | Juvenile Indigent Defense

Of the 288 individuals exonerated in New York since 1989, at least 25 were under 18 at the time of their arrest, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. More than 80% are Black or Hispanic.

With the third highest exoneration rate in the country, advocates say New York has decades’ worth of evidence indicating the need for change.

Huwe Burton, a Black youth from the Bronx, was just 16 when he was arrested in 1989 for allegedly killing his mother. Already traumatized after coming home to find his mother brutally murdered, he was denied an attorney and pressured into a false confession. He served 19 years in prison before being exonerated in 2019.

Others — including Kevin Richardson and Raymond Santana, once known as part of the “Central Park Five,” now known as the “Exonerated Five” — were only 14 when arrested.

Accused of raping a white investment banker jogging in Central Park, the five were interrogated for hours, lied to by detectives and denied access to an attorney. All were under 18 at the time. Four of the five were pressured into falsely confessing. Each was convicted and spent between five and 12 years in prison before being exonerated in 2002.

Past practices still used, 'Exonerated Five' say

Since their conviction more than 30 years ago, little has changed.

“What people may not realize is that what happened to us isn’t just the past — it’s the present,” Richardson, Santana and Yusef Salaam wrote in the New York Times earlier this year. “The methods that the police used to coerce us, five terrified young boys, into falsely confessing are still commonly used today.”

In an email, an NYPD spokesperson defended the department’s youth interrogation practices, adding that while the right to counsel is critical, the proposed legislation replaces the judgment and reason of a juvenile’s parent or guardian with that of an attorney.

“While the bill may be well-intentioned, we believe that parents and guardians are in the best position to make decisions for their children,” the spokesperson said.

But research shows that parents of teens involved in the system often have misunderstandings about their rights and the rights of their children and are too often manipulated by police, according to Hanon-Caron.

"When parents are in the interrogation room, we know from the research that they either stay silent or they encourage their kids to confess, often because the police are pushing the parents to do that,” Hanon-Caron said. “That means that children and adolescents can't rely on help from their parents — they need an attorney to advise them. Without the protection of an attorney, youths’ constitutional rights are meaningless and our youth are left at serious risk of giving a false confession, which almost always results in a conviction."

Advocates say ensuring juveniles have access to attorneys will prevent false confessions, which not only lead to unjust convictions, but cause crime rates to rise.

"The other big consequence is not just for the child, it means that the real perpetrator goes free and often that person goes on to commit additional crimes,” Haney-Canon said.

“So of the proven false confession cases that we know about, in the cases where they could identify who the real perpetrator actually was, more than half the time by the time they discovered who that person was they had already committed additional violent crimes that were only possible because the police believed that false confession," Haney-Caron added.

That’s precisely what happened in the Central Park jogger case.

"The young lady, one of the young last victims that the Central Park rapist raped, was a young pregnant Latina woman," Salaam said at the rally. "She could have been alive enjoying her family, enjoying her baby that was also killed in the process, enjoying her husband — but she became part of the collateral damage, or the collateral effect, I should say, of the system getting it wrong."

The NYPD maintains that requiring youth to have access to an attorney creates an unattainable bar and could be “detrimental to public safety.”

“Even in cases, where this bar is met — where someone’s life is in imminent danger and the juvenile knows about this — the department must wait until the juvenile has consulted with an attorney before further inquiry,” an NYPD spokesperson said. “Further, the bill essentially eliminates any ability to investigate or inquire about a violent crime that has already occurred and which may have been committed by that juvenile or another.”

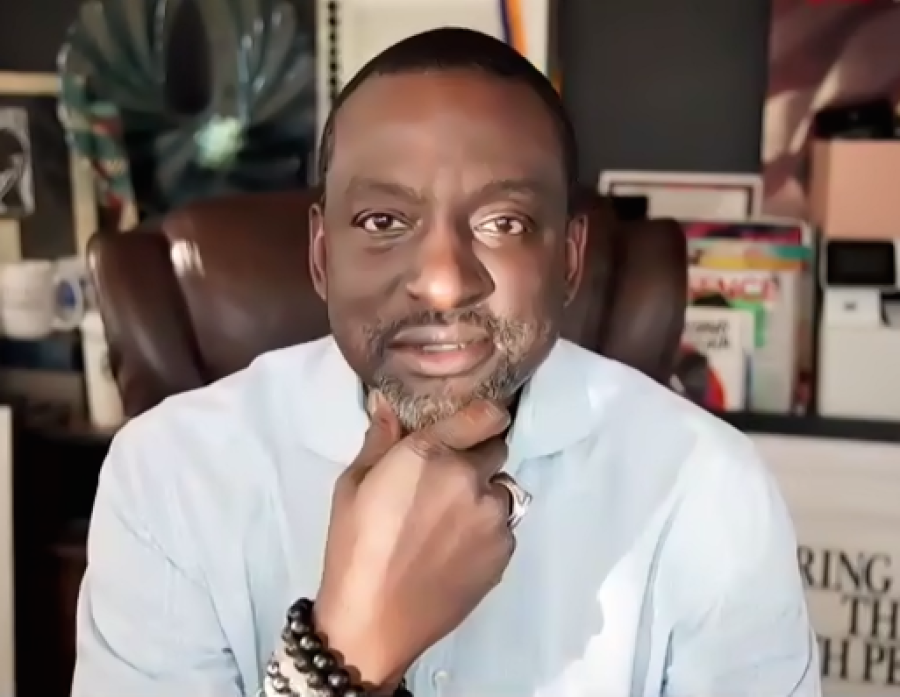

Bronx Connect

Rev. Wendy Calderón-Payne

The Rev. Wendy Calderón-Payne, executive director of Bronx Connect, equated coerced confessions and false convictions with fraud on the part of the New York City police union.

"I have contracts with the city. If I was fraudulent with young people, I would lose my contracts,” she said. “I don't understand how unions are allowed to stand being fraudulent with youth and I don't understand how we give people their retirement or we keep people employed being willfully fraudulent with young people."

Calderón-Payne also scoffed at the notion that children are developmentally mature enough to waive their rights.

"Children and youth are not allowed to enter into a contract, they're not allowed to get married at a certain age, they're not allowed to go and join the military without parental consent — there's all these things that we do to protect our young people,” she said.

“To think that young people are allowed to give away such an important right without legal counsel is horrendous."